Editorial

Elusive quest for justice

Many of the stakeholders in the transitional justice process sorely lack the commitment to see it through.

Fourteen years is a long time in politics. Nepal has seen sea changes in its political landscape in the past 14 years after the Maoist combatants safe-landed in mainstream politics, and raised the curtains on what would be called a new era. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed by the Maoists and the then government envisioned integrating the former combatants in the forces and rehabilitating those who couldn't be integrated; socio-political transformation of the country; and justice for the victims of cases of gross human rights violation. While the integration of the combatants has taken shape, and the transformation of the country materialised to some extent, the idea of justice has never really taken centre stage as of now.

Political parties may want to give a spin that the transitional period has ended with the holding of the Constituent Assembly elections, or drafting the constitution, or even holding elections to a federal structure. However, the transitional justice process is not yet over. And, going by the goings-on in the twin commissions established to take the transitional justice process to a logical end—the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons—there are too many roadblocks on the road to justice today.

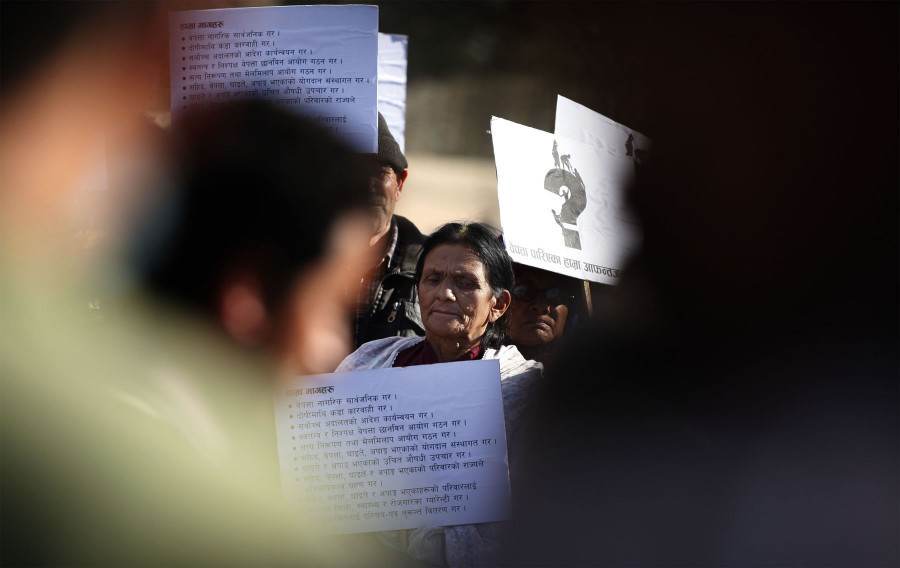

As per their recent reports, the truth commission has 63,718 cases and the disappearance commission has 2,506 cases to look into. Five years after they came into existence, the twin commissions are yet to investigate a single case. What's more, the commissioners are reportedly lobbying for an extension of their terms by four years saying it would take that long to complete the investigations. And this is what human rights activists, civil society members and families of victims feared right from the beginning. The commissions have once again shown what they have turned into: Institutions that are not interested in providing justice to the families of the victims, but in dilly-dallying to the extent of making the idea of justice obsolete altogether.

Aiding the commissions in their inefficacy are the political parties that become brothers in arms when it comes to defending each other's crimes and dismissing the intent of the transitional justice process. Clearly, the political parties seem to think that the victims' families will get tired enough of seeking justice to leave the demand altogether. But open wounds cannot be left untreated, for they may get worse in course of time. The only way out is to heal the wounds through the right approach. A stitch in time saves nine. Nepal has repeatedly committed before the international community and at the UN forum about concluding the process, but it has failed to uphold its commitment. Moreover, Nepal's presence at the UN Human Rights Commission could be questionable if it continues to fail in delivering justice to the victims of human rights abuse.

There is no doubt among Nepalis, and especially the families of the victims, that the insurgency was an extraordinary situation; and that the normative ideas of the criminal justice system do not apply as they are in insurgency-era cases. If the right approach towards finding the truth about killings, maiming and disappearances during the war era is to be taken, there is certainly hope for reconciliation or forgiveness and a way out for a shared future. Transitional justice, therefore, is not an other-worldly idea altogether. What it just needs is a firm commitment from all stakeholders to see it through. Such a commitment is sorely missing among many of the stakeholders in the transitional justice process.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu