Editorial

Beyond the rhetoric

High-level political visits hopefully set the tone for tangible economic gains

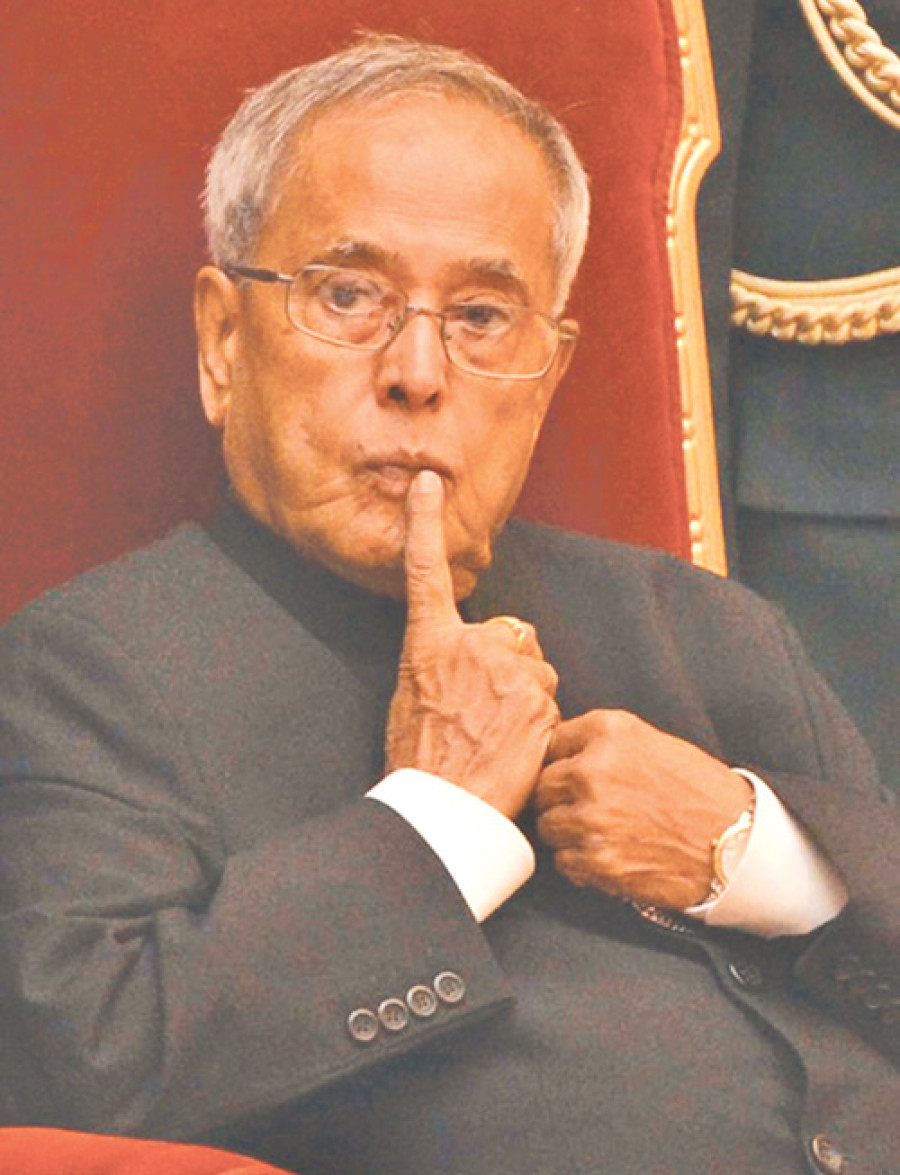

Indian President Pranab Mukherjee’s visit to Nepal has major symbolic significance. He is the first Indian President to visit Nepal in 18 years. Though a president and not an executive prime minister, he has a long history of political engagement with Nepal.

The visit is an indication that the Indian government wants to deepen relations with Nepal as part of its ‘neighbourhood first policy’. This goal was of course articulated soon after Narendra Modi became India’s prime minister in 2014.

However, the momentum that was generated during Modi’s two visits to Kathmandu could not be sustained due to the deterioration in relations caused by the crisis over Nepal’s new constitution and India’s undeclared border blockade. After many months of poor relations, the current visit underscores that New Delhi is keen to revive the warmth in bilateral ties and deepen them further. A number of bilateral mechanisms (the Joint Commission and Eminent Persons Group, for example), have now been activated, new infrastructure bilateral projects signed, and high-level political visits exchanged.

That said, while political engagements are relatively easy to get started, the popular narrative takes a while to shape. During Mukherjee’s visit, the Nepali public will be looking for indications as to what the Indian government now thinks of the four-and-a-month long undeclared border blockade that it had imposed last year on Nepal.

Yesterday morning, as the Indian President prepared to land in Kathmandu, #PranabDaSaySorry was trending on social media in Nepal. This follows sharp criticism of the Dahal government’s decision to declare yesterday a public holiday. Lest we forget, the blockade last year followed a devastating earthquake that killed close to 9,000 Nepalis and rendered close to a million homeless, easily the worst natural disaster in our living memory.

Some kind of atonement for New Delhi’s ill-thought out action last year would be in order and would go a long way in assuring the Nepali public that New Delhi is a well-meaning neighbour. The blockade in fact not only antagonised a very large section of the Nepali population, it also failed to effect any major solution to the political crisis in Nepal or to secure anything in the Indian interest.

If the Indian government truly wants to reach out to the Nepali population, it could start by admitting that the blockade was a mistake and that it only served to exacerbate the hardships of the Nepali people.

Such a measure will allay suspicion among a large section of the Nepali public that India could again resort to coercive instruments to achieve its foreign policy goals in Nepal. It is now clear that such methods can only backfire. In the case of the blockade, India may have tried to come to the aid of the Madhesi population, but by using coercive methods, it only contributed to deepening the alienation between the Madhesi and the Pahadi populations.

Another major irritant in the Nepal-India relationship is related with investment and development cooperation. Nepal has a long-standing complaint that Indian development projects are poorly implemented and delayed for long periods of time.

It is also time for the two sides to at least lay out a vision for long-term economic cooperation. There is a suspicion in Nepal that India continues to primarily view Nepal through the lens of security, and this has impeded economic cooperation. In recent years, for example, Nepal has been keen on trilateral economic engagement, involving China, India and Nepal. Over the long-term, this could help Nepal yield substantial economic dividends and also contribute to regional connectivity and, by extension, trade.

The Chinese government appears positive to this idea. However, indications from the Indian side are ambivalent. It appears that a section of the Indian population wants Nepal to remain under India’s sphere of influence and prevent a Chinese presence, economic or otherwise, in Nepal. But more recently, some sections of the Indian political and official class have demonstrated relative openness to the idea.

Mukherjee’s visit can be considered a resounding success if he delivers a clear message to New Delhi: Nepal wants assurances regarding long-term economic engagement, trade, transit and investment.

It would be useful to note here a couple of points from his interview with this newspaper (see the interview on Page 7). He has rightly urged Nepal and India to make their private sectors expand linkages in manufacturing and services, engage in regional supply chains and benefit from India’s growth story.

He also has urged that the two sides address market entry barriers and continue to take measures to facilitate trade and mutual investments. He also rightly points out that expeditious implementation of hydropower projects and promotion of investments between India and Nepal would not only contribute to reducing the trade gap but also to creating jobs in Nepal. That will have a huge political meaning too, for a large section of the Nepali population believes that as a much bigger economy and a regional power, the onus lies on India to assist its smaller neighbour in dire need of a growth spurt.

15.12°C Kathmandu

15.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)