Columns

Economic stagnation over decades

The policy failures to tap into emerging markets will be a missed opportunity for Nepal.

Durga Gautam

The era of mass production began when Europeans launched the Industrial Revolution in the mid-18th century. They took it to North America and Australia and helped these continents prosper. The revival of globalisation after World War II in many East Asian countries, including South Korea and China, promptly opened doors to multinational companies. The rest of the world has persistently struggled to run a new machine to create marketable value and is left out of the major global markets. A large part of South Asia, including Nepal, has stagnated for centuries, impoverishing its citizens.

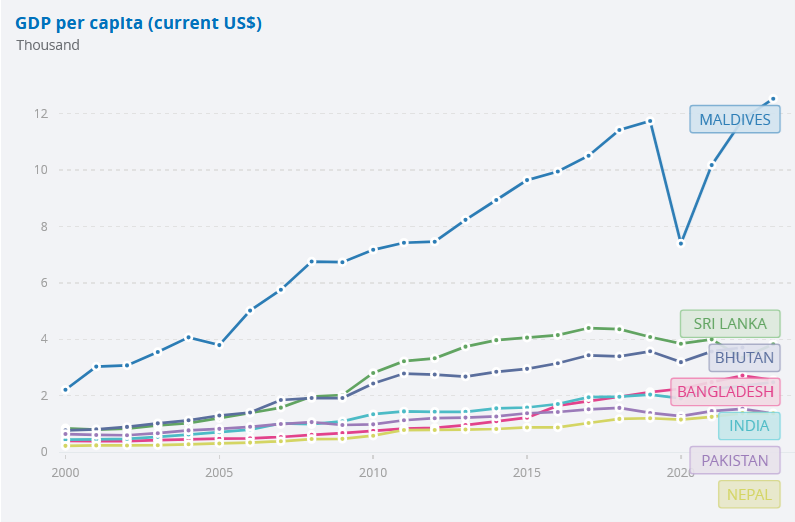

When one compares our nation with other South Asian countries regarding an average person’s standard of living, we appear to rest at the bottom of the chart for decades. Are some countries born poor and others rich? Daron Acemoglu, co-winner of the 2024 Nobel Prize in economics, said, “Nations are not like children—they are not born rich or poor. Their governments make them that way.”

Weak avenues of growth

More than 40 percent of Nepalis were living in poverty during the 30 years of the Panchayat regime headed by the King until 1990. Since then, a series of governments that assumed power under multiparty democracy has reduced the poverty rate to 20 percent. Yet, the country remains trapped as one of the world’s 50 least developed countries (LDCs). Escaping the poverty trap and sustaining economic growth requires finding new avenues where people become increasingly productive, economic resources are streamlined to their best uses, and strong political institutions facilitate nation-building by enhancing good governance. Unfortunately, our governments persistently failed to strengthen these key avenues of economic growth.

Economic stagnation is not entitled to a landlocked country, and financial success is not reserved for those with easy access to the sea. Otherwise, the Republic of Botswana would be stuck in the poverty trap forever and the Republic of Madagascar would have overcome poverty. What made the landlocked people of Botswana richer and the sea-locked Malagasy poorer? Each country worldwide has distinct geographic features, specific resource bases and unique cultural characteristics. Ultimately, it is up to the government to either harness these state qualities to expand collective benefits or misallocate them towards political patronage to enhance personal gains.

Unexploited resource base

A predominantly agrarian economy, like ours, consists of many small-scale farms in remote areas, growing various crops (vegetables, fruits, grains) and raising a smaller number of livestock. These farms are characterised by small land sizes and reliance on family labour, constituting a fundamental economic resource base. Thus, government initiatives and active roles in promoting family farms can significantly contribute to economic growth. However, if these farmers consistently face untimely shortages of seeds and fertilisers, lose access to credit resources, lack irrigation and storage facilities and cannot reach local markets, it not only hurts the farm sector but also breaks the economy’s backbone.

Nepal is a site of highland ecosystems, a heritage of ancient arts and cultures and has a vibrant mix of ethnic diversity. The country could be the leading destination for international tourism and ecotourism. So, what is holding our tourism sector from growing? Is it becoming a reliable foreign currency source or a quagmire of political malpractices, debt burden and public security risk? The country’s tourism industry does not go far enough if the outside world persistently sees dangers in our roadways and airways. Nepali airlines are still under the European Union (EU)’s aviation blacklist. Being air-locked can be much worse than being landlocked. People are also concerned about adding international airfields without concrete operational plans.

The remittance curse

With an annual average of 22 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over a decade, migrants’ remittances have become a lifeline for the country. These foreign income transfers shield against macroeconomic shocks and support poor families in remote areas. Strategic use of remittances to finance productive investments can help bridge the gap between rural and urban sectors, support essential infrastructure, and eventually shift the economy from agrarian to manufacturing and service-based. This will be akin to the role of foreign capital inflows in transforming the economies of many East Asian countries.

Nepal’s export of goods and services is less than 10 percent of GDP, and the country consistently faces high unemployment; the government has no choice but to continue exporting labour. However, much of the temporary benefits of remittances come at a high cost of youth migration and irreparable loss of productive human resources.

Since remittances bring foreign exchange reserves for the government—but without selling any products—and incomes for the recipient families—but without doing any work—less effort will be made toward diversifying the economy or increasing its tax base. Research shows that remittance “windfalls” may cause the so-called Dutch disease that will damage the country’s export industries.

Moreover, a large inflow of “tax-free” remittances tends to discourage households from monitoring the government’s behaviour and, in turn, incentivise the government to free-ride, leading to misappropriation of public funds, increase in corruption and decay of state institutions. The long-term costs of remittances appear to outweigh their short-term benefits Nepal’s economy.

Untapped giant markets

“If you are coastal, you serve the world, if you are landlocked, you serve your neighbours”, says Paul Collier, a development scholar, with a revealing statistic that if a landlocked country’s neighbours grow by an additional one percent, the country grows by a further 0.7 percent. Unfortunately, Nepal has become an exception in a prospering neighbourhood with no growth spillovers. China and India are rapidly catching up with the West and emerging as major global powers.

The policy failures to tap into these emerging markets, whether in the North or the South, will be a missed opportunity for Nepal’s economic growth. Long-term benefits of cross-border trade with such close geographic proximity could go far beyond the purview of Nepal’s cottage and small-scale industries. The country’s soaring trade deficits with India and China reveal the size of these forgone trade benefits.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu