Columns

Tug of war in Maldives

There is nothing new in the judiciary-executive clash over the Anti-Defection Law.

Smruti S Pattanaik

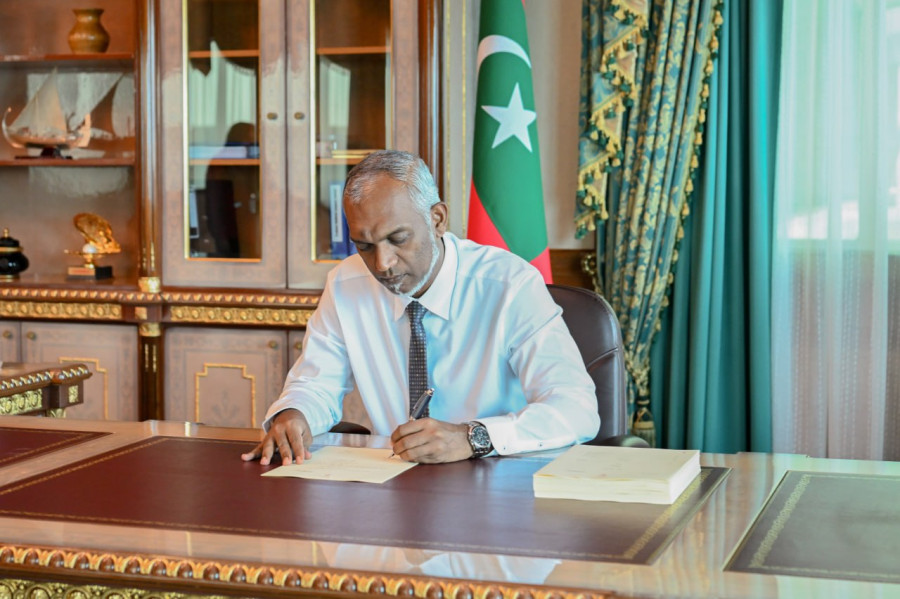

The Maldives’ judiciary is in crisis again, as President Mohamed Muizzu aims to downsize the Supreme Court. It is hearing the controversial Constitutional Amendment that strips lawmakers of their seats if they change their party affiliation or are expelled from the political party from which they were elected.

Defending the amendment carried out in November last year, the president expressed, “Members contest elections as representing a particular ideology or party and therefore there is a covenant between the elected member and the people of the constituency… the amendment to the Constitution will protect the covenant made by the members”.

This was part of the 6th Amendment to the constitution that included several other changes and was justified on the ground that it would “strengthen political accountability, safeguard national sovereignty and ensure public participation in critical national decisions”. The Constitutional Amendment Bill received 78 votes in favour, while 13 MPs—12 from the opposition Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) and independent MP Abdul Rahman—opposed it.

The opposition filed a case against the amendment in the Maldivian Supreme Court soon after the president ratified it. Notably, the amendment was presented, passed and ratified within nine hours. However, Muizzu’s style of passing this amendment is not new in the Maldives’ parliamentary history. In the past, President Abdullah Yameen also got approval in a similar manner when the Free Trade Agreement with China was ratified overnight without the opposition’s presence.

The MDP is the main opposition to the petition. However, prior to the hearing of the case by the Supreme Court, the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) removed three judges from the Supreme Court. The JSC is investigating a case where two of the judges—now suspended—were accused of interfering in a criminal investigation case and allegedly used offensive language against a former High Court Assistant Registrar in 2022. Interestingly, this case was taken for investigation by the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) only after the Supreme Court agreed to examine the legality of the 6th Amendment.

The Majlis, the Maldivian unicameral legislative body, passed a bill to downsize the Supreme Court by amending the Courts Act, which brought down the number of judges to five from the existing seven. In 2018, former president Yameen had also suspended two Supreme Court judges after the court’s verdict went against his political position. Muizzu served in the Yameen government in the past.

President Muizzu’s party enjoys a comfortable majority in the Parliament. He does not want legislators from his party to defect over disagreements with the party’s point of view. He has also accused the government of undermining the constitution and concentrating power on the executive. The opposition has been pressing the ruling party MPs to leave their party and run for election from the MDP. This was during a rally in defence of the constitution where former President Ibu Solih—Yameen’s successor and Muizzu’s predecessor—emphasised the freedom of the MPs to speak for their constituents.

Additionally, the MDP announced a contingency plan if the Muizzu government arrests their leaders who accuse the opposition MDP of being involved in terrorism. The opposition, however, announced another rally on the same theme, ‘defence of constitution’ on January 31.

History repeats itself

The judiciary-executive clash over the Anti-Defection Law is not a new occurrence. A history of the anti-defection bill shows that the MDP and the People’s National Congress (PNC) have different stances on the bill. Earlier, Yameen’s Progressive Party of Maldives (PPM) and now the PNC want to act against the MPs for switching sides, exacerbating the constitutional crisis. The MDP emphasises the freedom of MPs to choose whom they wish to vote for. Recent political history reflects the different positions of the two groups.

On February 1, 2018, the Supreme Court reinstated the lawmakers expelled by the PPM government following a judgement on July 13, 2017. The court argued that the Yameen government had not passed laws to make the expulsion constitutional and legal. Following this judgement, in March 2018, the Yameen government introduced the Anti-Defection Law to expel lawmakers of his party who had joined the opposition.

In 2017, 12 lawmakers from Yameen’s party defected to the opposition camp, which led the PPM to lose its majority in Parliament. The Maldives United Opposition had filed a no-confidence motion against Yameen and the Speaker of the Majlis. The Supreme Court verdict sanctioned the expulsion of 12 ruling party members for voting in favour of the no-confidence motion, even though they had renounced their party membership before the July 13 verdict. However, the law did not apply to independent lawmakers who violated the party whip and those expelled from the party.

Before his defeat in the 2018 election, Yameen ratified the motion to repeal the law that his government passed earlier. Interestingly, the same year, the Supreme Court clarified that the Anti-Defection bill is not a violation of the constitution while delivering a verdict on an opposition petition that challenged the law.

The opposition MDP introduced the Anti-Defection Bill in February last year, a watered-down version of the proposed law. However, in the proposed version, the MPs were required to voluntarily decide on their resignation if the person switched party affiliation.

Political crises involving the Supreme Court and the government have major implications for the country’s governance. Many of the laws in the past have been challenged in the Supreme Court. Each political party wants to stack the judiciary with loyal judges. Considering the Maldives’ nascent experiment with democracy, strengthening the judiciary and preventing executive interference will go a long way in building democratic institutions in the country.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu