Columns

Geopolitics of economic growth

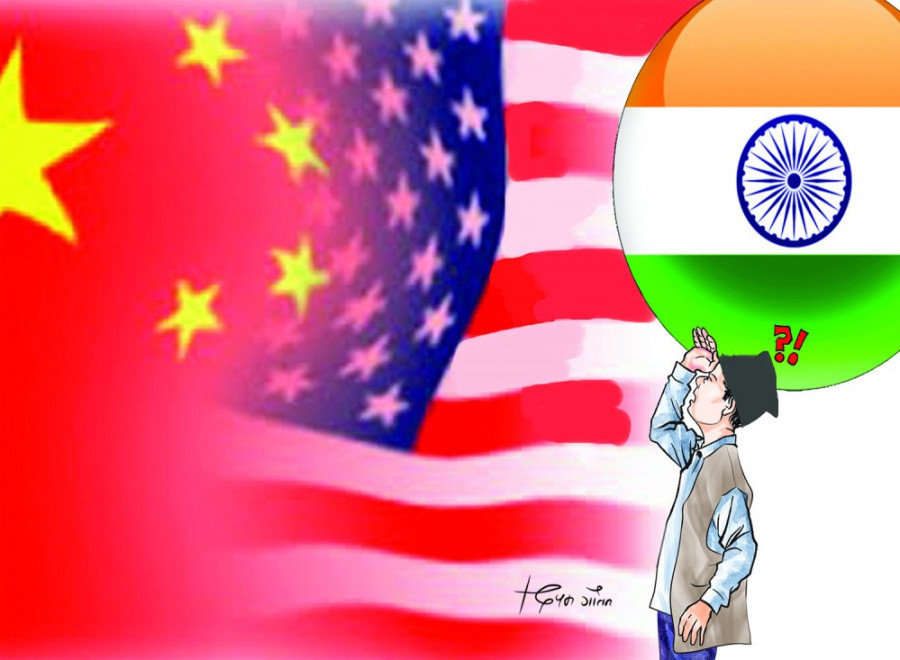

It is vital to consider the current coalition’s foreign policy and its impact on Nepal’s economic development.

Ajaya Bhadra Khanal

After a much discussed visit to China, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli presented a political report to the party’s central committee last week. The report repeated some of his entrenched views, redirecting sharp criticisms against the US and India.

Oli has turned the current coalition into a paradox. The coalition partners embody a long-standing ideological rivalry with differing views about democracy, development and foreign policy. They have been forced by fate to work together.

It is, therefore, important to consider how the current coalition is conducting its foreign policy and what impact it will have on Nepal’s economic development.

Oli’s foreign policy

Oli’s political report submitted to the party central committee aligns closely with China’s foreign policy interests. In the report, Oli claims that he seeks to “rebalance” and strengthen external relations and rejects working under external “order, direction or interest.” He praises the Belt and Road Initiative cooperation framework as a means to overcome landlockedness, diversify transit, facilitate trade and increase investment.

Most notably, Oli blames the US for increasing tension in the Asia-Pacific through its position on Taiwan and criticises India for obstructing regional cooperation and not resolving outstanding issues with Nepal (e.g., the border, the 1950 Treaty and trade imbalance). The report reflects wishful thinking, prevalent among the leftists and nationalists, that the India-China conflict is temporary and improved relations between the two will resolve Nepal’s problems.

His report helps to contextualise the outcomes of his China visit.

The first, of course, is the BRI Framework Agreement. In the negotiations over the Agreement, Nepal has managed to temporarily protect and promote its interests. However, China always has a long term view, and every agreement is viewed as a temporary arrangement. Even then, Nepal has shown vulnerability by promoting top leaders’ pet projects, proposing projects formally opposed by India, and failing to secure grants in exchange for BRI alignment and risky ideological positioning.

The second is Nepal’s ideological positioning. If we look at the nine MoUs and the joint statement issued during the visit, they reflect that China has been able to considerably advance its core interests, some of which directly conflict with that of the US and the West. In simple terms, Nepal has clearly aligned its foreign policy ideology with that of China.

The joint statements between Nepal and China from 2016 to 2024 reveal a systematic progression in bilateral relations, marked by expanding scope and deepening strategic alignment that serves China’s broader regional and global objectives. The latest joint statement shows that the relationship has evolved from simple bilateral cooperation to strategic alignment and ideological convergence on global governance issues. In particular, Nepal has expressed support for China’s development path, shared vision of international order and common opposition to “Western unilateralism.”

Strategic rivalry

Oli’s rise in the party coincided with his strong anti-Maoist stance during the peace process. His efforts to weaken the bargaining power of the Maoists, especially during the post-conflict phase, aligned with India’s interests.

However, since 2015, he has used anti-Indian nationalism to establish himself even further and opened the floodgates for Chinese interests to enter Nepal. The CPN-UML portrays this as a correction of foreign policy imbalance and implementation of an “independent” foreign policy that is in the interests of Nepal.

As the floodgates for Chinese interests opened after 2015, mostly due to close political relations between the Nepali communist parties and China, India began a policy of dissuading growing Chinese influence by restricting market access to Chinese investments.

India and China’s economic engagements, in the form of Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), show interesting dynamics. Both powers have committed similar amounts of grant and loan (India: $1.92 billion, China: $1.8 billion), with India maintaining steady disbursements and China’s aid fluctuating with political shifts and windows of opportunity.

In the FDI sector, India leads with Rs 103.5 billion across manufacturing (38.4 percent), energy (34.5 percent) and financial services (20.6 percent), while China’s Rs 35.5 billion focuses primarily (77.6 percent) on energy.

These patterns reveal two distinct strategies. India pursues what could be termed a “deep integration” approach, weaving investments across multiple sectors while building on historical ties. China, conversely, follows a “strategic sector dominance” approach, focusing intensively on specific sectors with large-scale infrastructure projects.

We are already seeing the results of this strategic rivalry in market access, including in the energy sector, the aviation sector and even in the trade of agricultural or manufactured goods.

A crucial battleground is Nepal’s energy sector, where India maintains significant market access leverage while China seeks strategic sector dominance. This creates a complex dynamic where Nepal must navigate between Chinese infrastructure initiatives and Indian market access, which remains vital for the viability of projects, including those under the BRI Framework.

The current coalition has not been able to maintain balance in Nepal’s foreign policy, or adopt the policy of strategic autonomy. There are clear indications that Nepal is gradually tilting toward China, and this tilt could adversely impact Nepal’s economic development trajectory.

This shift risks undermining the traditional privileges Nepal enjoys under the 1950 treaty with India and could potentially limit trade and connectivity opportunities with the country.

Strategic autonomy

Nepal’s foreign policy tends to swing with each political regime. During the Panchayat era, swings in relations with China and India were aligned with the interests and needs of the monarchy. Since 2008, shifts in relations have aligned with the fears, interests and needs of parties in power.

While the Nepali Congress has, at least since 1990, become close to India and the Western democratic forces, communists in Nepal have an affinity with the traditional communist blocs as well as with China. So, in terms of ideology and identity, Nepal’s politics is deeply polarised. This rift could widen if the current global and regional geopolitical rivalry between the US, India and China intensifies.

Although Nepal’s economic fundamentals show some resilience, particularly in energy and trade potential, these factors face mounting pressure from institutional flaws and kleptocracy. Geopolitical rivalry, while still manageable, can worsen political polarisation, affect infrastructure development and impact market access, which in turn can impact growth.

In order to withstand such strategic rivalry, Nepal must adopt a policy of strategic autonomy and maintain trusted relations with India, China and the US.

To address these challenges, Nepal must prioritise developing stronger diplomatic negotiation capabilities, generating knowledge, building cross-party consensus on foreign policy and maintaining strategic autonomy.

Without these improvements, Nepal risks further erosion of its balanced foreign policy position and increased vulnerability to external pressures.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu.jpg)