Columns

Why intra-party democracy is essential

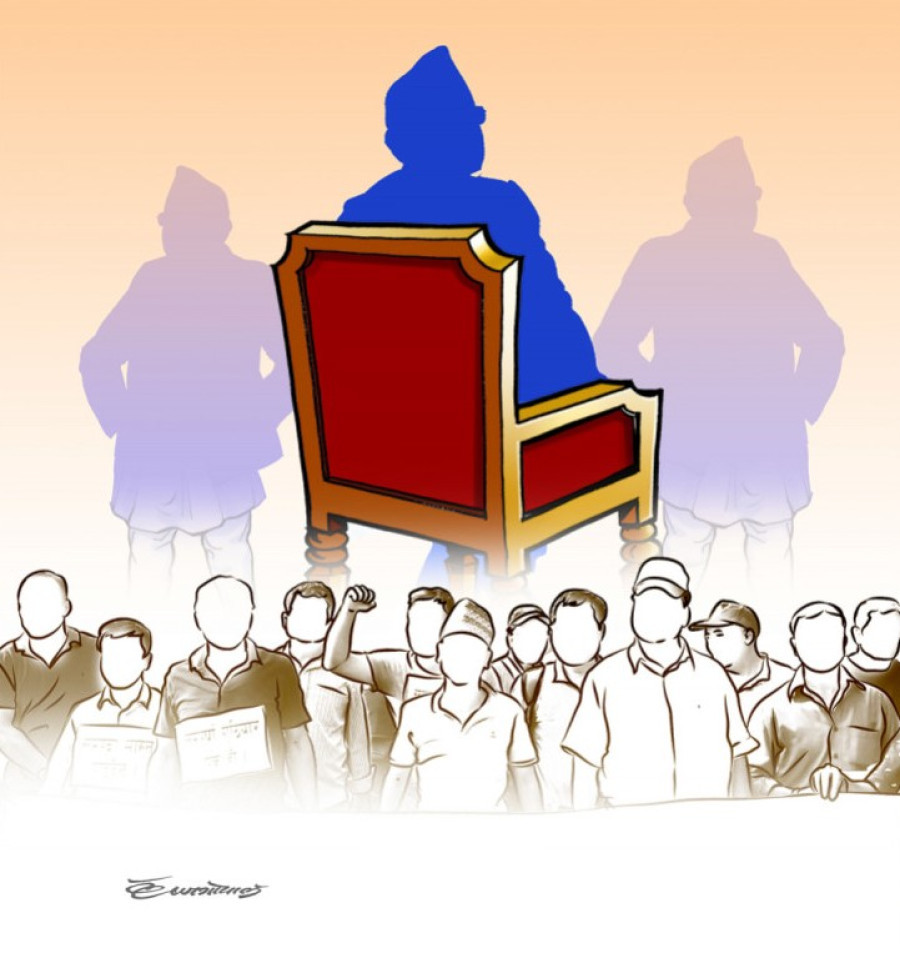

True democracy cannot thrive when political parties are profoundly undemocratic.

Pawan Adhikari

In Nepal’s political landscape, the same politicians remain at the centre of power for decades. Take the current Prime Minister, KP Sharma Oli, for example, who exercises near-absolute control within the CPN-UML. Many politicians express frustration with his leadership in private conversations, yet few dare challenge him. Why? Their self-interest—often tied to political appointments, election tickets and funding opportunities—prevents them from questioning his legitimacy.

This, however, is not unique to the UML. Maoist Centre’s Pushpa Kamal Dahal has maintained an iron grip on his party for over 35 years, with efforts to unseat him ending the political careers of many challengers. In the Nepali Congress, Sher Bahadur Deuba has centralised support around himself, not necessarily because of his “supreme power,” but the self-interest of those around him. Nepali politicians aren’t motivated by policy or ideological alignment; they are driven by personal benefit, perpetuating a system where individual leaders dominate parties, stifling dissent and competition.

Even new parties, such as the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) founded by Rabi Lamichhane, replicate these dynamics. Built around the cult of personality, Lamichhane dominates his party, much like CK Raut in the Janamat Party. Lamichhane’s party is currently protesting against his supposed “politically charged” arrest, even though he has been taken into custody for cooperatives fraud. In Kathmandu, Balen Shah’s rise is based on his public image. He has openly admired leaders like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and American President Donald Trump and has adopted their political tactics.

Such a trend suggests a dangerous pattern in Nepali politics—political power is increasingly concentrated on individuals rather than institutions. The solution lies in cultivating genuine intra-party democracy.

The illusion of leadership change

The idea of "exit policies" within parties like the Nepali Congress has generated some debate. Genuine democracy within parties requires more than setting a retirement age or term limits. It necessitates a political culture where leadership exits are probable because of robust internal competition. Hence, an exit policy is hardly the solution to the problem of entrenched leaders. It may push an individual out, but it does not address the broader undemocratic culture that has taken hold within Nepal's major political parties. Exit policies fail to offer a real solution because they do not change the structure or system of power within parties. We need a political culture where leadership transitions are not just probable but a constant possibility.

Top leaders must realise that their position is always vulnerable—subject to internal challenges from qualified, competent alternatives. Emerging leaders who can challenge their authority should pressure them. This can be possible only if political parties stop being loyal to only a single leader. The parties must become open spaces, allowing new ideas and fresh leadership to rise. Unfortunately, none of this is currently possible in Nepal. Intra-party democracy—where there is a regular, fair and open process for leadership selection—has largely been absent from our political system.

Decaying democracy

How can we expect leaders who suppress internal party democracy to champion democratic principles at the national level? The same leaders who ruthlessly crush internal opposition, cement their rule as the only viable option, and do whatever it takes to maintain power cannot be trusted to safeguard the country’s democratic values. This pattern mirrors authoritarian regimes, where leaders present themselves as the solution to all national problems.

Self-interest is at the core of Nepal's political dysfunction. Leaders surround themselves with loyalists who expect political and financial rewards for their allegiance. This dynamic creates a toxic environment where factions form around personal interests rather than ideologies or policies.

True democracy cannot thrive when the internal structures of its most vital institutions—political parties—are profoundly undemocratic. Power may shift from a Koirala to a Deuba or a Nepal to an Oli, but this doesn’t signify progress. These represent a reshuffling of elites rather than a fundamental shift in how power is distributed and exercised. Without dismantling the factional politics driven by self-interest, the larger democratic project remains in jeopardy.

The path forward

For democracy to be strengthened, Nepal must look inward—at the parties forming its political system's backbone. This does not necessarily mean ousting long-standing leaders like Oli, Prachanda, or Deuba and replacing one leader with another. What is needed is a transformation in how parties operate internally.

Leadership should not be seen as a lifetime appointment. It needs to be accountable not only to the public but also to the very institutions it helms. Only when Nepali political parties embrace intra-party democracy can the broader political system become more democratic. This will require systemic reforms that foster transparency, competition and merit-based advancement within parties. Without these changes, Nepal’s political system will remain a breeding ground for authoritarian tendencies under the guise of democratic leadership.

It’s important to recognise that the alternative to a dysfunctional democracy is not radical system change but meaningful reform. Democracy is not just about holding elections or transferring power between individuals. It is a political culture where power is not held by a small clique of people but shared, opposed and renovated.

9.93°C Kathmandu

9.93°C Kathmandu