Columns

Elephants on the move

The elephant corridors in eastern Nepal and north Bengal are crucial conduits in their migration.

Akhilesh Upadhyay

Bang on the banks of the Mechi River, Bahundangi gets in the news each time elephants “wreak havoc” in the village in eastern Jhapa, on the border with the Darjeeling Terai. To anyone following the episodic news outside the village, and in Kathmandu, the elephants are intruders from India, wild beasts with very little regard for human lives and livelihoods.

The story is a little more complex than that.

In the age of social media, the elephant menace gets ever so magnified. Short videos show villagers running helter-skelter: Helpless men, women and young children trying to chase the elephants away from their homes and crops howsoever they can. The human-animal conflict is never an easy sight.

When the elephants then enter the neighbouring east Bihar, local communities in India similarly hold that the tusker trouble has its origin in Nepal. Most of these stories are reported as isolated events; so are the solutions that come into play. Villagers try to chase the elephants away from human settlements and keep vigil to bar them from re-entering their neighbourhoods.

In 2016, the National Trust for Nature Conservation (NTNC), with support from the World Bank, constructed an 18-kilometre fence in Bahundangi, right by the Mechi River.

But the electric fences can never offer a one-stop solution. Over time, elephants—among the most intelligent animals—find ways to circumvent them. Often, the fence is washed away by floods—as some 300 metres of it in the current monsoon in Bahundangi. In some cases, the solar-powered battery panels are stolen, which can render the fence useless.

In all this, the only concern for many local government officials—the CDOs, Chief District Officers; and the DFOs, District Forest Officers in Chandragadhi, for instance—is to hush it all up. To them, the news of elephant attacks or elephants in distress should not travel to Kathmandu. Why face a new set of controversies, get caught up in the Centre-grassroots contest and invite needless enquiries? Any initiative that especially requires cross-border cooperation with Indian officials is even more complicated.

What attracts the elephants

Elephants can smell maize from miles away and farmers in Jhapa grow plenty of it. Various hybrid varieties now grow abundantly round the year, very unlike earlier when it used to be a seasonal crop. On the other hand, the Darjeeling Terai and further east, the Dooars, are studded with large tea gardens—among the world’s largest. Elephants don’t eat tea plants, but the tea gardens along the foothills of the Himalaya are havens for elephants in their long migration routes in the plains of Bengal, southern Bhutan and Assam.

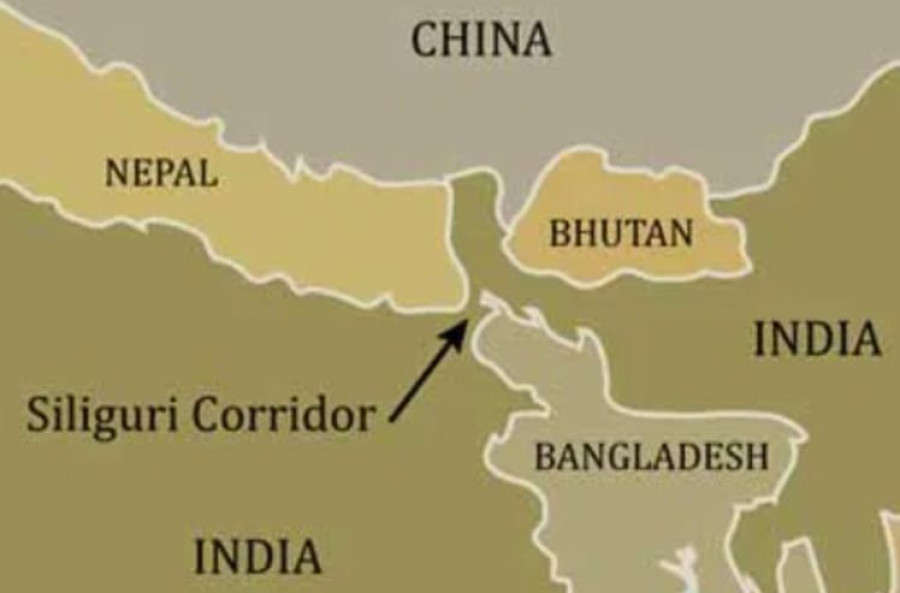

The elephant corridors in eastern Nepal and north Bengal, on the Indian Chicken Neck, are crucial conduits for their movements. The Mahananda-Kolabari corridor links the forests of Bengal to Nepal. However, as water holes, grass, and trees get scarce, elephants venture into human settlements in search of food and water.

Further, as the temperatures warm up due to global warming, elephant sightings have been reported at higher elevations in Ilam, which borders the Darjeeling Hills. Among the wild elephants spotted in the elephant corridor in Jhapa, Morang and Sunsari, some are local herds (raithaney), which have been found to stay there for extended periods.

Borderland and nonstate actors

Bahundangi notably is in the borderland. Family and kinship ties, and businesses are spread across the border to Panitanki, Siliguri, Darjeeling and beyond.

When elephants create menace and run into trouble in the settlements close to the Nepal-India border, it is the Rapid Response Team that springs into action, often in the middle of the night. Its members are residents of local communities on either side of the border river. The locals are in the line of fire, and they are the ones who get into immediate action. Kathmandu, Biratnagar and even Chandragadhi are distant administrative capitals.

In north Bengal, adjacent to eastern Jhapa, the elephant habitat lies in Darjeeling Terai and Jalpaiguri districts. The elephant population extends from the Teesta River char (sand and silt islands in the river formed by floods) through Mahananda Wildlife Sanctuary and southern forests of Kurseong Division, up to Bahundangi, observes Jayanta Mallick in ‘Trans-boundary human-elephant conflict in the Indo-Nepal Terai landscape’. Increasingly, the landscape, interspersed with human habitations, has become an extensive human-elephant conflict zone in terms of human mortality, crop depredations and loss of properties.

In Nepal, elephant populations are concentrated in four places. Bahundangi is the transit point for migration in the east. Nepal has enlisted elephants as protected species under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1973 and is among the 13 Asian elephant range states.

A ‘mega-herbivore,’ elephants have long-range dispersing behaviour, frequently coming into contact with human beings in the course of their movement. Although their poaching is not a threat in Nepal, according to the National Trust for Nature Conservation (NNTC), elephant conservation is challenged by habitat fragmentation, obstruction of migratory routes and human-elephant conflict.

Though the challenge of elephant conservation has been documented in academic essays and journals, its cross-border nuances are not much discussed in the public sphere. Elephants as far away as Assam migrate to Nepal, passing through the plains of Darjeeling. In the process, they pass through human settlements, where they damage houses and crops, kill humans and get killed themselves too.

Without a cross-border conservation regime and recognition of the role of non-state actors, such as the Rapid Response Team in Bahundangi and Naxalbari in north Bengal, the human-animal conflict will continue to be grossly misunderstood.

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu