Columns

Equality conundrum between unequals

It’s extremely difficult, even if not outright impossible, to resolve competing claims over contested territories.

CK Lal

Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli was initiated into Marxist-Leninist-Maoist (MLM) politics of Jhapali Naxals quite early in his life. He began his political career by participating in what is euphemistically called the “elimination of class enemies”. He was caught, prosecuted, found guilty of involvement in manslaughter and was sent to rigorous imprisonment.

Premier Sharma Oli received all his adult education in incarceration. He has been socialised with some of the most hardened criminals in the harshest of conditions. Adult education in a prison isn’t the most appropriate way of acquiring social refinement. He received a royal pardon after spending 14 years in various jails and came out a bitter man determined to succeed.

Once one understands the ‘education’ of the Khas-Arya chieftain Sharma Oli, it becomes easy to make sense of his earthy proverbs, insulting turns of phrases and bigoted expressions. He chooses his words carefully so as to hurt his target without sounding explicitly abusive, profane or slanderous. He once used a Newari phrase, Maka Phui, to dismiss the movement of Janjati because a translated version in any other language would have sounded inappropriate and insulting. He termed the human chain of Madheshis in 2015 as Makhe Sanglo. A literal translation of the expression would be ‘a chain of flies’, but the simile in Nepali language also means the net that a spider weaves to catch flies.

The entire Khas-Arya intelligentsia comes out in full force to protect its chieftain with a charitable explanation whenever Sharma Oli spouts any calumny that has the potential of having a double meaning. Unfortunately, what he recently said about Nepal’s land ‘neighbours’ lacks any nuance. Frustrated with not getting the attention that he thinks he deserves, he let out a stream of invectives that were clearly not meant for the Chinese. He said in Nepali that he doesn’t want the relationship to be chhudra and jaali with its neighbour.

Clearly, words have been carefully chosen, and sentences meticulously crafted to cover the intended impact of the statement. According to Pragya Nepali Brihat Shabdakosh, jaali can also mean fraudulent and hypocritical behaviour. The term chhudra literally means being mean, but it also suggests being ‘mean-spirited, vile, ignominious and dishonest’. It is possible that Sharma Oli has nothing but good intentions for Nepal’s southern neighbour, but his increasingly harsh statements are unlikely to do much good to improve bilateral relations.

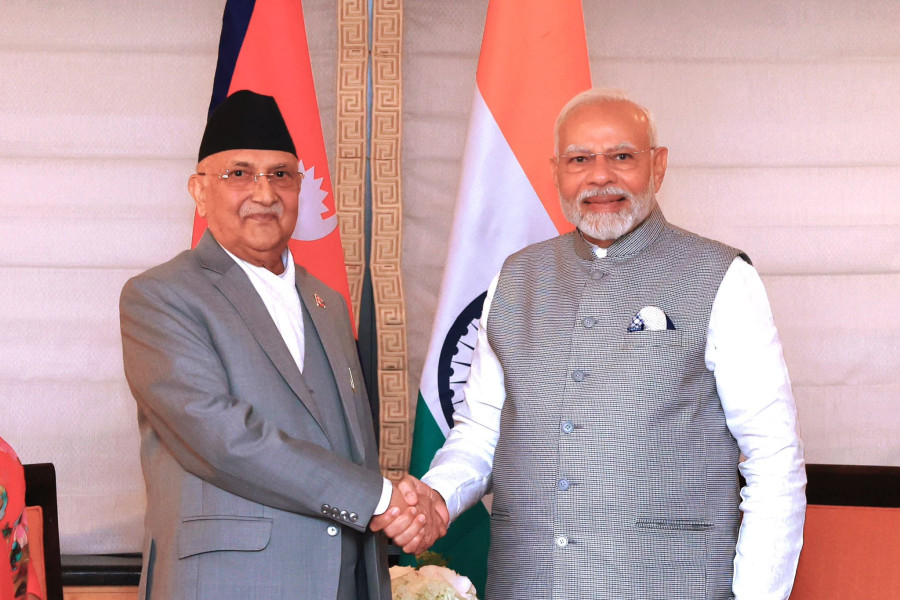

The courtesy extended to him for a meeting in New York may just be an opportunity for the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to show that Nepal is not yet off the radar of India’s Neighbourhood First policy. But unless the tongue at the top level of Nepal is restrained, it’s extremely unlikely that concerned minds from both countries can manage longstanding irritants.

Border row

The textbook system of Nepal is basically uniform, with a slightly guided freedom for private schools to add some other teaching material of their choice. The Ministry of Education sanctions the contents, and the Janak Education Material Centre (JEMC)—a parastatal with a monopoly over the production and distribution of textbooks—takes them to schools all over the country. The JMEC hadn’t produced a single geography book till the second decade of the 21st century that had Lipulekh and Limpiyadhura anywhere on it. What exactly changed in 2020 that prompted the then Pratinidhi Sabha to unilaterally amend an existing map enshrined in every bilateral and multilateral agreement till then? Other than the paroxysm of jingoism, it’s difficult to come up with a logical answer.

Sovereign countries acquire or lose territory primarily through four means—war, settlement, reward or occupation. The last time Nepal fought a war with the East India Company, it lost considerable territory. There has been no fresh border settlement between Kathmandu and New Delhi. Since the Kashmir imbroglio, no international agency has been allowed to interfere in South Asia; hence, the question of a tribunal rewarding Nepal doesn’t arise. As far as the occupation goes, Indians clearly have an advantage at the source of Mahakali. All claims based on the disputed documents of the colonial era are play acting at best.

Premier Sharma Oli probably never attended a proper school for long. He can thus be forgiven for not knowing much about Nepal’s academic, official and diplomatic maps that had been in circulation till 2020. However, the parliament that adopted the revised version was full of learned scholars who had attended some of the best universities in the world. When a chauvinistic director also writes the script, fear of being labelled ‘anti-national’ drives all possible dissenters into silent acquiescence.

Treaty tantrums

It’s extremely difficult, even if not outright impossible, to resolve competing claims over contested territories. Irrespective of the nature, no government can afford to appear as if it’s giving up control over even a small piece of land. Despots fear the judgement of history, though King Mahendra apparently didn’t and had little hesitation in bartering away a bit of it to the north and the west to acquire international support for his absolutist regime. Democratic rulers are afraid of the voters’ wrath. All one can do about border disputes is let them fester until the line of actual control ultimately acquires international legitimacy and domestic acceptance almost by default.

Unlike the sanctity of territorial boundaries, treaties between consenting countries aren’t written in stone. The 1969 Vienna Convention defines a treaty as "an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law”. When ground realities change, competent signatories to the instrument can renegotiate terms, reach to an agreement and decide to incorporate mutually agreed-upon amendments into the existing treaty or replace it with a new one. Such instruments usually require ratification by sovereign authorities of consenting countries.

The Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the Government of India and the Government of Nepal was signed on July 31, 1950, in Kathmandu. The instrument has a termination clause: “This Treaty shall remain in force until it is terminated by either party by giving one year's notice.” Perhaps India interprets any attempt at amendment as its termination and is hesitant to formulate a new treaty altogether.

A lot has changed in Nepal since the 1950s. King Birendra’s Zone of Peace proposal was meant to circumvent the treaty without terminating it. When the Eminent Persons’ Group was formed in January 2016, perhaps Kathmandu and New Delhi had different expectations from their recommendations. Even though the report hasn’t been made public, the South Block probably expects its contents about the treaty of 1950 disagreeable and has decided not to open it. The clamour in Kathmandu that it be accepted in New Delhi is akin to flogging a dead horse: Unless forced upon one party by another or mutually agreed upon, no changes in bilateral relationship are practicable.

Perhaps it’s a little too early and too much to expect that a brief meeting between Premier Sharma Oli and Indian Prime Minister Modi in New York could clear the misunderstanding between two of the closest countries in the world. Ancient ties take long to transform.

8.22°C Kathmandu

8.22°C Kathmandu