Columns

On the Samsodhan Mandal’s Pathashala

Its work provided one model of how Nepal Studies could be done in Nepal.

Pratyoush Onta

One of the first group experiments of Nepal Studies in the mid-20th century came in the form of a research collective which was later named Samsodhan Mandal. It was founded and led by the late Naya Raj Pant (1913-2002). Pant had studied Siddhant Jyautisa (astronomy) with Padmakar Dvivedi and others in Banaras for about six years during the 1930s. A key text that had greatly influenced him during this period was Bhaskara’s Siddhantasiromani, a 12th-century text. Dvivedi was interested in ancient history and tried to inculcate that interest in his pupils as well. According to Pant, he used to meet with his guru outside of school hours to learn history and other things. From the mid-1930s, Pant started studying the history of Nepal. After returning to Kathmandu in 1938, he came into contact with Baburam Acharya (1888-1972) who gave him old documents to study. Later he came into contact with Sardar Rudra Raj Pandey (1901-1987) who facilitated a six-month research stint for him in the Guthi Office.

Pant writes, “From all these [interests and connections], I learnt a bit about Nepali history. When I found mutually contradictory statements [stories] in the history written by foreigners, I began to lose my respect for them. I [then] decided to progressively revise the history of Nepal.” In 1941, Pant was hired by the Ranipokhari Sanskrit Pathashala to teach Jyautisa. From around the same time, he is said to have immersed himself in the further study of Sanskrit grammar and Kautilya’s Arthasastra.

Starting from the early 1940s, Pant started a private Pathashala in Kathmandu to train students in Sanskrit, Jyautisa and history. What was his vision then? In Hamro Uddesya ra Karyapranali, a text said to have been written around 1957 but published only in 2002, Pant wrote, “A century has passed since we started taking English-style education. We know first-hand that we have been (mostly) unable to learn work-effective knowledge, or when we have managed to do so, it has not succeeded in our country and produced good results. Now is not the time to remain idle. There is no other way but to rejuvenate our own ancient knowledge. Even though it might require great perseverance and a lot of time, we have to do research on our knowledge and advance it further; we have to maintain our own traditional experiences, and find our own path/method. Only if we manage to do this will we be independently able to make our country more prosperous....It is with this belief that we are engaged in studying-teaching Sanskrit education to rejuvenate our knowledge. The Sanskrit Pathashala has been opened for this purpose.”

Just as one founder of the Nepal Sanskritik Parisad (estd 1951) had highlighted the need to cultivate self-identity to shed the cultural dependency on Europe, Pant stressed the need to rejuvenate traditional Sanskrit education as the highway for Nepal’s prosperity. Regarding the particular modality of his Pathashala, in an article published in 2014, historian Yogesh Raj has suggested that Pant had been “impressed by the strict Gurukul-style teachings of an obscure Pandit Genalal Chaudhary” whom he had encountered in Banaras.

Pant’s Pathashala adhered to some fundamentals as integral to the process of training as a historian. These included mastery of Sanskrit, palaeography and epigraphy, rote memorisation of some key texts, and rectification of factual errors committed by other historians based on source criticism. When enrolling at the Pathashala, the students had to pledge that they would not use it as a ladder to subsequent education in foreign languages. The guardians of the students also had to sign another piece of paper saying, “From the bottom of my heart, I believe that great knowledge can be attained and livelihood earned even when one does not study English or other foreign languages.”

In Pant’s Pathashala, mastery over Sanskrit was given great priority. In the words of his son and disciple Mahes Raj Pant, this enabled the students “to have independent access to many a discipline from the whole range of Sanskrit literature.” Rote learning as part of the ‘traditional method’ was a fundamental tenet of the senior Pant’s training while he was a student, and he replicated this method in his own Pathashala. Recitation of specific texts from memory was how gradual competence was demonstrated in this school. Being able to critically edit old documents and texts of inscriptions and write commentaries on them was another part of the training. The projected time-period to master the skills emphasised in this school was a total of eight years.

Following the guru’s command, the students in Pant’s Pathashala mostly invested their academic energies into doing research on the history of Nepal. This work began to thrive after the Rana regime ended in 1951. Its members started to publish pamphlets of Itihas-samsodhan (Amendments of History) from 1952. In the words of Mahes Raj Pant, “In those pamphlets the students pointed out with documentary evidence the errors committed by the so-called scholars in dealing with the history of Nepal. That work of the group attracted a lot of popular attention at the time. Some of the Ithihasa-Samsodhana pamphlets contained harsh words to shock those who were incompetent to write the history of Nepal….The task of the group helped to highlight various aspects of Nepalese history and gave a fresh impetus to the reconstruction of a correct and complete history of Nepal.” In these pamphlets, Mandal students deployed what Raj has called “multi-layer source criticism.” Their “rule of evidence” was “primarily about sustained engagement with the fidelity of evidence and often solely that.”

At its largest, the Mandal’s Pathashala had 32 students out of which 21 were involved in the history samsodhan work. However, by the time the Samsodhan Mandal got officially registered in the early 1960s, only ten, including the guru, remained. One member of the group, Gyanmani Nepal (1933-2024), had already graduated by then and returned to his home in eastern Nepal to start a similar Pathashala. Several others had quit the group for various reasons.

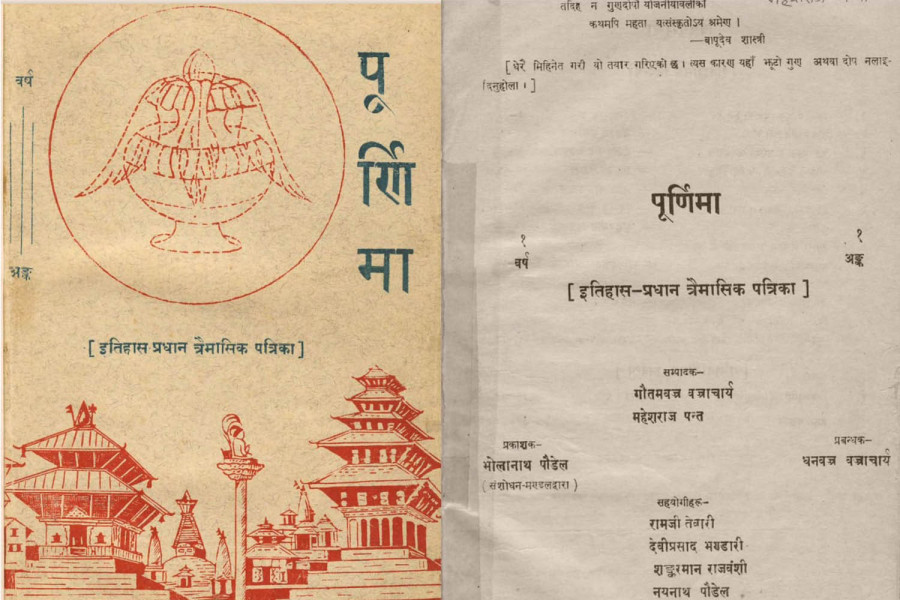

By the end of the 1960s, the Mandal’s scholars had generated a corpus of booklets including several dozen ‘Amendments of History’. A consolidated and revised collection of 50 such ‘Amendments’ was published in 1962. They had also published a series of Shavadhan-patras, challenging the published work of various scholars and cautioning them against unethical academic practices such as not acknowledging the published work of the Mandal scholars. They had also published several volumes of primary documents, including 12 issues of the quarterly Abhilekh-sangraha, some critically edited historical texts, and over 20 issues of its quarterly journal Purnima (estd 1964). By 1970, the Pathashala had trained individuals such as Dhanavajra Vajracharya (1932-1994), Gyanmani Nepal, the late Shankar Man Rajbanshi, Gautamvajra Vajracharya, Mahes Raj Pant, and several others as historians.

Several members of this Pathashala went on to make significant contributions in history-writing of Nepal. They provided us with a relatively secure knowledge of the chronology of the successive ruling dynasties of Nepal from the Licchavi period to the Shah dynasty, made public various types of new historical documents and other sources and set exacting standards for evidence-based history-writing. The main bulk of their contributions fell under the domain of political history, but some of them also made significant contributions to a broader social history.

Articles in the essay form and length were the preferred outputs of the members of this school, and interpretive historical narrative of the monograph length was not their strongest mode of written output. Writing in 1984, one of Mandal’s members, Mahes Raj Pant, stated, “The greatest contribution of this group was that it inspired the natives with the idea that given proper education, we can carry on research, and we ourselves are competent enough to reconstruct our past.” In the assessment of Yogesh Raj, the work of the Mandal contributed to “epistemic diversity” in historical knowledge production in post-Rana Nepal. Raj adds, “Mandal scholars took evidence as resources whose rigorous criticism would lead to a true and ‘scientific’ knowledge about the past.”

Samsodhan Mandal’s Pathashala was plagued by financial problems from its very beginning. After an initial phase of great activity in the 1950s and 60s, it could not find the means to retain its students and reproduce itself in intergenerational terms. By the time of the death of its initiator, Naya Raj Pant, in November 2002, the school had been reduced to the guru and his two historian sons, Mahes Raj and Dines Raj Pant. While talking to a journalist in the immediate aftermath of the demise of the senior Pant, his two sons described their father’s attempt at an alternative to formal university-based education and degrees as a “failure”.

The senior Pant and his sons have often said that, among other reasons, the antagonism of those whose work had been amended by the Mandal’s students led to the downfall of its Pathashala. In their view, given that those who were ‘attacked’ in its pamphlets were powerful members of Nepal’s intellectual elite, the latter conspired to disband the Pathashala. While there is no doubt that those whose works were ‘amended’ were mostly not pleased to have been put under the Mandal’s scanner, the idea of them getting together to conspire against the Pathashala’s institutional longevity is a bit hard to digest. The Pathashala initially succeeded because the pupils mostly adhered to the utopian visions of the guru Naya Raj Pant and participated in his experiment as his disciples. However, as they gradually became expert historians in their own right and had to earn a living to support their families, discordance between the fiscal needs of the pupils and the school’s inability to generate an income to keep it running became all too apparent.

The school never had a system whereby the pupils were expected to pay regular fees to take lessons. In the early decades, the guru supported his family with his salary from the Ranipokhari Sanskrit Pathashala, and its scholars occasionally got some stipend from various sources (including Nepal Sanskritik Parisad) to critically edit historical texts. As part of their remit as trainees, the older students also tutored the younger ones in the Pathashala. Following the establishment of Tribhuvan University in 1959, university-credentialed individuals began to find jobs in new state, para-state and private institutions. By the early 1970s, the intergenerational transfer of knowledge began to be mediated by more complex institutions supported by the state and market forces. Hence, the Mandal’s Pathashala model and the vision of which it was a part, began to look less attractive to those who were already its members and to younger folks who were its potential members. When the late Dhanavajra Vajracharya, one of the Mandal’s most competent and committed members, quit it and joined TU in 1971, the attraction of this Pathashala was surely on the decline.

In the context of the immediate post-Rana Nepal, the experiment that was Samsodhan Mandal Pathashala was important because it established a firm tradition of Nepali historical scholarship based on a critical reading of the evidence. This school demonstrated what could be achieved through a commitment to a kind of historical scholarship that had been in practice in scholarly traditions in different parts of the world until the mid-20th century but mostly absent in Nepal. We should also note that the Pathashala was a home-grown effort that relied on the collaboration of several individuals for its success and for at least a few decades, its work provided one model of how Nepal Studies could be done in Nepal.

20.9°C Kathmandu

20.9°C Kathmandu