Columns

Dalit women in local governance

Political parties must understand that quotas don’t ensure adequate and meaningful resources.

Sajhana Tolange

For the first time in Nepal, all but a few among the 753 local governments are represented by Dalit women. In some wards, quota seats for Dalit women members remain vacant because political parties could not nominate anyone. The Local Level Election Act 2017 mandated political parties to fill 40 percent of seats in local governments with women. This act mandates that there should be three women in the ward, including one in the executive position and two in the ward committee. Furthermore, among two women members, one must be a Dalit. This led to the entry of many Dalit women in local governance. In 2017, a total of 6567 Dalit women were elected and 176 seats remained vacant. Similarly, 6620 women were elected in the local level in 2022 and 123 seats remained vacant.

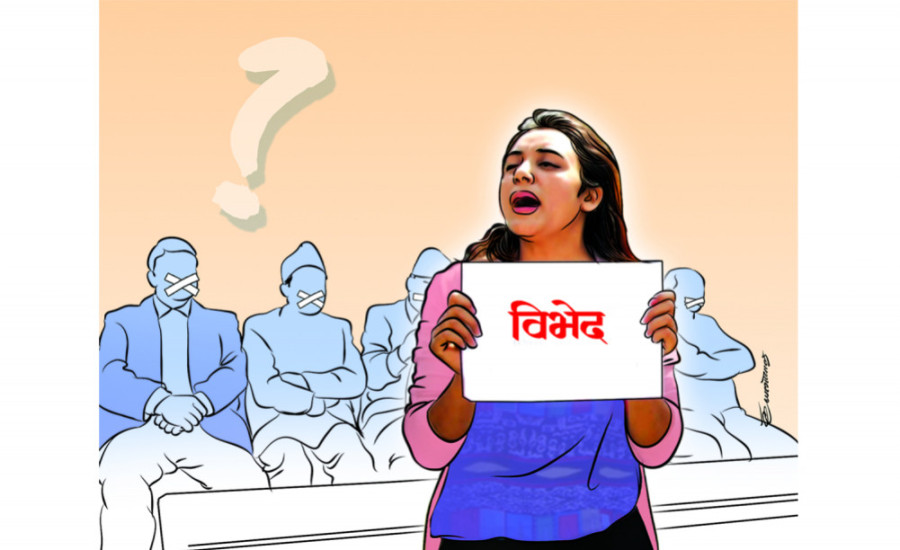

According to the 2021 census, Dalits comprise 13.8 percent of Nepal's population. Dalits are socially, culturally and structurally discriminated against, based on the notion of purity and impurity. The status of Dalit women is the lowest compared to Dalit men and other categories of women, resulting in extreme vulnerabilities, exclusion and marginalisation. While political participation of Dalit women is increasing compared to the past, their representation is limited to quotas only. Very few Dalit women have been elected to decision-making positions such as chief/deputy chief and ward chair.

Meaningful representation

Why and when do "participation" and "representation" become meaningful? Social scientists argue that active and meaningful participation is crucial not only for gender equality but also for social development. Factors including opportunity, functionality, capability, critical voice, leadership and decision-making are essential to meaningful participation. At a recent workshop titled "Dalit women in politics", participants lamented the lack of meaningful participation and representation of Dalit women because they aren’t included in decision-making. They are omitted from policy planning and programmes on development issues and budget allocation. While such practices were more prevalent in the previous local governments, they are a reality today as well, despite Dalit women representatives raising their voices.

Multiple factors hinder the meaningful participation and representation of Dalit women in politics. They experience unacceptance from people as politicians and representatives and lack support for any kind of initiation and activities. Reservation does not work if the society doesn’t accept women as politicians. It is crucial to engage Dalit women in local governance to ensure inclusion and so quota seats were introduced and implemented. However, Dalit women politicians suffer from caste-based discrimination, stigmatisation and oppression. Elected Dalit women representatives say they face discrimination even from their colleagues after their caste belonging is made public.

Have quotas worked?

There has been a rise in the number of countries having reserved quotas or opening spaces for women’s political participation in national parliament, government and public spheres in European, African, Eastern and American countries. A greater numbers of countries have more than 30 percent of women’s participation and representation in politics after implementing reservation and quota policies. According to Esther Duflo, the quota system is a helpful procedure to ensure representation of disadvantaged groups such as women or ethnic minorities. Duflo says that without reservations, weaker groups who are socially, politically and economically deprived and backward cannot be represented.

In Nepal, social inclusion was brought into existence in 1997 to ensure the inclusion of backward, excluded and marginalised communities. As per Om Gurung, before 1990, the participation and representation of indigenous people, women, Dalit, Madhesi and other excluded groups were very few and not represented proportionally. Yet, due to a lack of theoretical and practical knowledge of social inclusion, many people spread hatred against the communities using quotas. Moreover, there is not much debate among all the excluded and deprived groups and communities in Nepal about the necessity and feasibility of positive affirmative action and social inclusion.

Punam Yadav argues that quota policies increase women's representation in politics and also strengthened their position in family and society. However, the case of Dalit women has been different since they always faced caste discrimination and prejudice. Nevertheless, some such women concede that they got an opportunity to develop their political careers at least nominally. A Dalit woman ward member from Chandragiri Municipality says she faced increased discrimination after she became a ward member. Her experience aligns with that of women worldwide, especially marginalised women, who face several obstacles in political participation and representation.

Moreover, patriarchy is seen to restrict women's leadership and rise in the political sphere. For Nepal's Dalit women, caste-based prejudices and Brahmanical patriarchy are the major and foremost barriers, as they are neither accepted by society as politician or human being.

What next?

Dalit women ward members face several challenges. But does this mean that quota seats for Dalit women must be removed? No. Instead, Dalit women ward members need more training to enhance their leadership and capacity skills. They further need opportunities for growth and spaces where they can raise their voices. Furthermore, there should be budgetary provisions for engaging Dalit women. Political parties must understand that quotas that don’t ensure meaningful resources and support are inadequate.

Most importantly, caste-based prejudice must stop. The state should provide legal and psychological support if anybody is discriminated against. Dalit women, in addition to Dalit men, continue to face discrimination in social and political spheres. Caste and gender are socially constructed identities, and we must put all efforts into dismantling the systems that perpetuate inequality, discrimination and violence.

15.62°C Kathmandu

15.62°C Kathmandu