Columns

BP, Mahendra and history

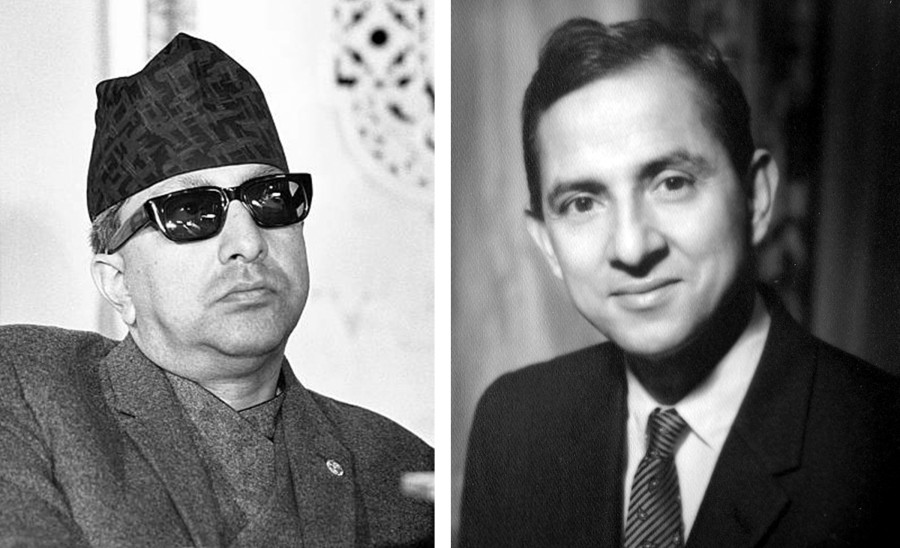

King Mahendra cleverly took up the plans of action prepared by BP Koirala and fulfilled some of them.

Abhi Subedi

I heard scholars trying to figure out the nature of the creatively productive years that the important political leader BP Koirala had to lose in prison in the panel discussion at the BP Koirala literary festival on September 11 in Kathmandu. It turns out that events do not follow a pattern that we imagine or recall at one point of time. I find this topic eloquent, but as said by poet TS Eliot in his poem “Gerontion”, “History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors”, it is difficult to say what an individual lost or gained in history. This is a subject of discussion.

The discussants dwelt on what BP Koirala would have achieved had his time not been wasted in prison at the most important time of his life and that of the nation. In one important sense, the discussions were hypothetical but important. But this is a recurring theme in history that speaks of good political leaders, social workers and writers not being able to serve their societies with their great ideas and plans because of the encroachment of dictatorial regimes in their lives. History speaks eloquently about it. I was impressed by the intelligent albeit hypothetical arguments made by the panellists on the occasion.

Irony of history

It is also important to see how King Mahendra operated after sending BP to prison. Studies including political tomes written by political scholars of Nepal and abroad like Leo Rose, Lok Raj Baral, Krishna Khanal, Devendra Raj Pandey and others show the conditions of the king’s actions and those of the political leaders including those of the Nepali Congress and communist parties who joined King Mahendra’s system and rose to power and prominence. Devendra Raj Pandey has written how King Mahendra cleverly took up the plans of action prepared by BP Koirala and fulfilled some of them. This is a common theme and irony of history. BP’s own analysis of the king’s psyche is also important. The fiction writer and a very good character creator, BP has said important things about the mind of the initially lonesome and later ambitious monarch.

What strikes me mainly is the course of events that happened in Nepal after King Mahendra staged the coup in 1960. Historians and his close supporters and champions of his ideologies all agree that King Mahendra was a shrewd ruler. Historian Triratna Manandhar cites the views of Surya Bahadur Thapa, a very close person of Mahendra, about the king in his memoir Mera Nau Dassak (1979 BS). Thapa says the king was a shrewd person who spoke less and listened to others’ opinions. (154). He cleverly played with the course of events after dissolving the elected Parliament and sending BP Koirala to Sundarijal prison where he spent the most precious eight years of his productive life.

By the same token, those years were very crucial for Nepal’s transformation which, it is natural for us to imagine today, would have been important for Nepal’s transformation had BP Koirala got a chance to work. But it is important to see how King Mahendra manipulated the mood and the events of that time. It is important to follow the king’s deft understanding of the aspirations of the youths and to try to see what gripped their minds at that time. Mahendra tried to understand the euphoria of the youths under different situations. He did so to consolidate his grip on the country.

I want to write a few words about the nature and mood of change at that time. It would be appropriate to mention a phenomenon of euphoria that people of different generations have experienced in Nepal. It would be particularly worth recalling some clashes of euphoria and derailments. I was in the final year of my school when BP went to Sundarijal prison. A unique mixture of euphoria and discontent that I saw in the Sixties and Seventies especially among college youths deserves some mention. The euphoria of change that the youths experienced then was political, which was generally against the Panchayat system introduced by King Mahendra. To follow a political line and to evoke some ideologies was the character of the mood of change at that time. Political ideologies had a strong grip in the minds of the students.

The activism of the Nepali Congress was one and the sway of communism was the other. The Panchayat system, despite its networks and autocratic modus operandi, was not able to exercise control over the activities of the youths. But as said above, King Mahendra was a very deft player. Here I want to evoke a theory, a revelation that remains ignored by historians and analysts alike. That is the concept of “metapolitics”, borrowed from Antonio Gramsci. This Italian Marxist of the 1920s and 1930s said a few things about the psyche and working style of dictators. He said if the dictator was clever and quite foresighted, he would win the support of writers and artists for his action. He would even create institutions for them and give them facilities and privileges. He would do so as long as no threats or challenges came to his regime from them. King Mahendra did exactly that.

Dictatorial king

King Mahendra created the institutions of writers and even encouraged them to write freely for he saw no challenge to his regime from them. Mahendra enjoyed praise from the poets of Nepal. Later in the Sixties, the youths adopted various ways of life. The police hardly questioned when they encountered people with hippie modus vivendi at different times of the day and night in Swayambhu and Kathmandu town during Mahendra’s rule. My own experience on occasions also proves that. Gramsci is right, the dictatorial king’s strategy was to keep the writers, youths, artists, musicians and poets in their respective spaces and consolidate the system of dictatorship. Ironically, this pattern was operative when BP was freed from jail in 1968; it continued up until King Mahendra’s death in 1972 and a little beyond. The conditions changed during the reigns of his sons. Birendra’s rule was different from Mahendra’s in many ways. History took a different turn. People, mainly the youths, became more proactive. The interim Parliament declared Nepal a “federal democratic republic” on December 28, 2007. The last Shah King Gyanendra left the palace.

The condition of euphoria among the people, especially the youths, has become complex, energetic, media-savvy and more confident. The various channels of communication, from the tangible printed means to the online diversities including lately the tweetosphère have overturned the familiar concept of means and methods. The colloquium once again brought BP Koirala and King Mahendra on the same forum in these changing times. Talking to Ewa Domanska, historian Hayden White said, “Historical past is simply 'absent' rather than no longer existing.”

8.83°C Kathmandu

8.83°C Kathmandu