Columns

Land equity for food security

Food insecurity will continue to rise if the government fails to protect agricultural land.

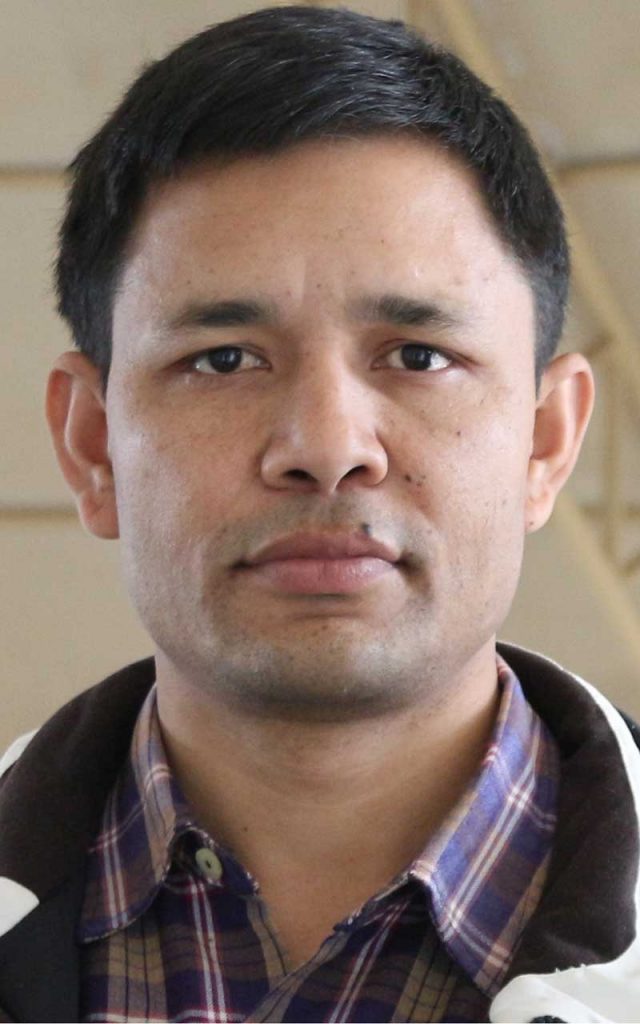

Jagat Deuja

Nepal confronts a moderate level of hunger, ranking 81st out of 121 qualifying countries with a score of 19.1 on the Global Hunger Index. However, the country’s growing dependency on food imports paints a bleak picture of its food security situation. From mid-July 2022 to mid-May 2023, Nepal imported agricultural and commodity goods worth Rs250 billion from 184 countries. Unfortunately, the intervention to improve food security from the government and non-government sectors is more technical than structural, which fails to identify and address the causes that have gradually led the country to severe food insecurity. The land question is often overlooked, but it must be understood and addressed to effectively tackle food insecurity.

In the last week of July this year, I participated in a discussion on agricultural issues in Gadawa, Dang. Srijana Chaudhary, who farmed vegetables on rented land, informed us that she had to abandon farming because the landowner terminated her contract. The landowner wanted to rent the land to a company from Chitwan that was searching for land for large-scale banana farming. The landowner took Chaudhary’s rented-in land back as the company offered a higher rent. This severely impacted Chaudhary and her neighbours’ food security and livelihoods, leaving her unable to financially support herself to seek treatment despite having serious health issues.

This case highlights the strong connection between food security, agriculture and land. It is easy to foresee the increasingly severe crisis that Nepal’s agriculture and food security sector will face in the near future. One of the preventive measures is establishing a comprehensively addressed land-related issue, but both the government and the organisations investing in the agricultural sector have ignored this.

During the same week, the UN Food Systems Stocktaking Moment was convened in Rome, Italy, emphasising the significant contribution of small-scale farmers to global food systems and offering solutions to sustainability challenges. However, the delegates didn’t discuss the issue of land distribution and the conversion of agricultural land for other purposes besides food production. Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal participated in the event but failed to address the fundamental questions concerning the food security of marginalised communities.

Land tenure and food security

Land tenure security of the actual tillers plays a significant role in ensuring food sovereignty in Nepal. The Land Reform Act of 1964 recognised the tenancy system, allowing tenants long-term land access. However, the tenancy provisions were abolished in 1997, aiming to end dual ownership between landowners and tenants. This was a crucial rage for tenancy reform as the land separation between the land owners and the tenants had not been completed. Furthermore, the incompleteness of the reform discouraged the landowner and tenant from investing in agriculture.

Another common tenure practice in Nepal is sharecropping, in which the landowner allots land use to sharecroppers for a specific number of years. The landowner’s ability to terminate the arrangement at any time, as it lacks a written deal, is the major drawback of this arrangement. Hence, sharecropping cultivators are discouraged, leading to a growing area of cultivable land going fallow, with an apparent negative consequence for the country’s food security.

With ongoing unplanned urbanisation and the absence of rigorous land use planning, converting agricultural land for non-agricultural purposes is widespread. In Nepal, the constitutional rights over ancestral private land also accelerate land degradation as families divide their land among family members, increasing fragmentation and resulting in land conversion for commercial purposes and inappropriate land use.

Land inequality is the oldest and most fundamental type of wealth inequality. The wealthiest 7 percent of households own around 31 percent of agricultural land. Half of Nepali farmers own less than 0.5 hectares of land. An estimated 1.3 million families are landless and in informal shelters in the country. Without addressing this unequal land distribution, the food sovereignty goals of the country would be hard to meet.

Protecting the fertile land

The Right to Food and Food Sovereignty Act, 2018, has been enacted and brought into force. This is a welcoming step. It seeks to bridge the gap regarding the “right” and “access” to food and its security. However, the rights of the peasants and landless people, as well as the considerable stress on the equitable development of agriculture, are inadequately included in the food sovereignty framework. The law does not fully come into force without food rights and sovereignty policies. Sadly, five years have passed since the enactment of the law, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock has failed to establish the necessary rules.

Meanwhile, the government recently lifted the restrictions imposed on land plotting in the name of revitalising the country’s economy, raising serious concerns regarding agricultural land protection from the perspective of food sovereignty.

Access to land plays a central role in ensuring food sovereignty in Nepal. In the given diverse geo-ecological regions and agricultural practices, equitable and appropriate land distribution supports local food production, reduces dependency on external sources and fosters self-reliance, eventually enhancing the country’s food security.

Land, agriculture and food security cannot be strengthened solely through central planning and efforts. This has already proven unsuccessful. A comprehensive analysis of land, agriculture and food security at the community and local levels with meaningful participation of the landless and peasants is required. The authorities should properly address the issue of access to land. The concrete effort should be targeted to enhance family farming and protect the landless and small-scale farmers. Food insecurity will continue to rise at an accelerated rate if the government fails to protect agricultural land, smallholders and peasants, particularly from profit-making agricultural companies.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu