Columns

Caste killing progress

Nepali Sarkis could have created luxury leather goods and become another Louis Vuitton.

Mitra Pariyar

Caste kills. Not just Dalits, but also the country’s economic progress. Caste has long been a major barrier to the nation’s overall development. The sooner we realise this, the better. This is the thrust of my argument here.

If we consider the situation of Nepal on the world stage, it has essentially become what might be called a “Dalit nation”. In the popular imagination, Dalit implies someone who’s very poor and dependent upon others for survival and who lacks power and prestige. Isn’t this the position of my country in the international community?

Nepal is naturally beautiful and has been blessed with rich natural resources. This is the dominant narrative anyway. It does boast some of the tallest mountains in the world, as well as a very moderate and pleasant climate. What reduced the Switzerland of the East to such poverty and backwardness? Why hasn’t it still not found its economic footing?

Historians, social scientists, economists and other analysts must ponder this problem critically. They must think outside the box and examine the root causes of the problem. There may be many external factors hindering development, including, in the main, competing geopolitical interests. More so now as neighbouring China and India rise as global powers. It’s important however to examine the country’s intrinsic issues as well, not least structural problems.

Caste system

Caste hierarchy has trumped Nepal’s development. The state-sponsored caste system has hampered inter-ethnic and caste unity, and nipped development in the bud. Government officials, policymakers, journalists, academics and others should properly understand this issue and make it central to the development discourse.

They could start perhaps by reading Fatalism and Development, written by famous Nepali anthropologist Dor Bahadur Bista. This remarkable book was published in 1991, shortly after the advent of multiparty democracy and the subsequent restoration of freedom of expression. Bista argues here that the caste system has greatly impeded the country’s modernisation and economic advancement.

The Shah kings and Rana prime ministers crushed the seeds of development early on by constructing a vertical social structure, based on the Hindu caste hierarchy. With the advice and support of Bahun men educated in Vedic Sanakritic literature from Indian towns like Varanasi. As a result of the long rule following traditional Brahmanic principles—as mandated by Dharmashastras like Manusmriti and Parashara Smriti—society became highly religious and spiritual. And casteist. The rigid caste hierarchy and its belief systems made people fatalistic. A popular belief in the karma theory greatly undermined creativity and innovation needed for the country’s overall progress.

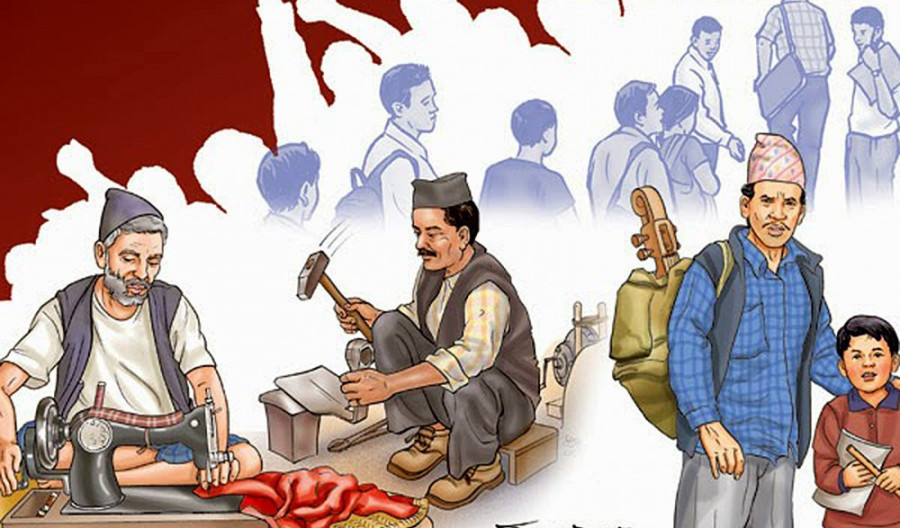

I believe the negative effect of the caste system on national development and modernisation can be easily understood through the historiography of the suppression of Dalits. They comprise people traditionally skilled in trades—such as fashion designing, folk music, ironwork, shoemaking—that are critical for running society and for developing the country.

The Industrial Revolution started in Europe, circa 1760s, after coal, iron and steel became easily available. Many other metals were also discovered and developed for industrial purposes. But there was no possibility of Nepal joining the league of industrialised nations because, inter alia, blacksmiths and metal workers were—and still are to a degree—defined as low castes or untouchables (using the Code of Manu) and banished from society. In return for their vital role, they have long been subjected to indignity and injustice.

Treated as some kind of loathsome and lowly creatures, and officially reduced to a status worse than slaves, these traditional experts in metallurgy had no scope for mechanising and modernising their traditional trades. Because these occupations were/are loaded with stigma, members of the upper or cleaner castes would not learn these skills.

Other artisan castes suffered a similar fate at the hands of upper caste Hindu rulers. They were made to work for their upper caste masters for hardly any return. Under the highly exploitative patron-client system, blacksmiths, tailors, leather workers, drummers and singers were reduced to begging. They survived on leftover foods and wore used and old clothing donated by the upper castes. All this was state policy, as is clearly stated in the 1854 Muluki Ain (Legal Code).

In their zeal to subordinate the people skilled in vitally important trades, the upper caste Hindu rulers (and their Bahun advisers) unwittingly stamped on national progress. The Western world learned to treat blacksmiths and tailors, and other artisans, better after the advent of, among other things, Protestant ethics (as classical sociologist Max Weber has famously argued). But Nepal never saw anything like Protestant ethics to challenge the caste order dictated by St Manu.

The world’s top luxury fashion company Prada was started by Mario Prada and his brother in 1913 in Milan, Italy, as a leather goods shop. Now the city of Milan has become a global capital of fashion and design. Likewise, Louis Vuitton started out as a luxury leather goods company in France. Nepali Sarkis are traditional leather craftsmen, but they had no right to develop their trades and to commercialise them as in Italy, France and many other countries. Thus both the leather worker community and the nation lost the opportunity to progress.

It is possible to assume that if they hadn’t been so oppressed, the traditional fashion designers from the Damai community would have also developed world class luxury brands like Gucci and Chanel and Armani and Hugo Boss. That could have turned Kathmandu or Pokhara or some other town into a fashion hub of the world, like Milan in Italy. The export of designer and other clothing could have possibly brought billions of dollars in revenue.

Things are changing

Things are indeed changing to some extent in Nepal. The upper castes have also started engaging businesses traditionally seen as shameful—such as gold and silver jewellery and tailoring. This is a sign of caste losing its grip. But it is too early to be hopeful. Caste hierarchy is still pervasive, and many people would rather beg for a living than engage in stigmatised trades like tailoring and shoemaking. Fashion designing and gold jewellery and similar other “low caste” businesses now run by the upper castes mostly employ designers and workers from their respective castes.

Yes, the Hindu monarchy is now a thing of the past, and Nepal is now a secular country. But sadly, nearly all of the government ministers and influential civil servants and other decision makers are exclusively high caste Hindus. They do not see caste hierarchy as an impediment to national development. There are no policies and programmes to free society from Manu’s laws and guarantee free competition. The latter is key for the advancement of trade and business—which is a pre-requisite for the economic progress of any country.

8.26°C Kathmandu

8.26°C Kathmandu