Columns

Maps and more

When our government adopted a new map of Nepal, not half an eyebrow was raised in New Delhi.

Deepak Thapa

The inauguration of India’s new Parliament building last month was duly greeted in Nepal with indignation for a mural therein having the effrontery to show parts of Nepal within India. Knowing how prickly the “Buddha was born in Nepal” crowd is about even a hint of appropriation of that rather pointless honour—not to mention the abundance of knee-jerk India-bashers—the Indians could have done better than find ways to needle them further.

The first the world came to know of the mural was via a Tweet by India’s Parliamentary Affairs Minister Pralhad Joshi who appears to have been carried away by the occasion and gushed in his native Kannada (which Twitter helpfully translates): “The resolve is clear—Akhand Bharat.”

Hackles were raised in Nepal as well as Bangladesh and Pakistan for the perception that the painting represented India’s expansionist design under the current government of Hindu zealots. With the allusion to “Akhand Bharat” (Undivided India), the pipe dream of these same folks, coming from the heart of the Indian government, the comment could not be ignored so easily. Even if perhaps the most appropriate response would have been to laugh it off as in one of the responses to Joshi, “[United Nations] pls note, and merge Nepal Bangladesh etc etc with [I]ndia..... Joshi ji has resolved.”

India played down the controversy by referring to the image as simply a portrayal of ancient history: “The mural in question depicts the spread of the Ashokan empire and the idea of responsible and people-oriented governance that [Emperor Ashoka] adopted and propagated.” With the mural’s shaded parts of South Asia corresponding to the extent of the 3rd-century BCE Maurya Empire and with the presumably faux inscription in the Brahmi script in the foreground alongside a replica of an ancient panel showing Ashoka with his queens, that certainly appears to be the intent. Thus, while it incorporates places that are not part of the nation-state of India, it also leaves out portions of its south that the emperor never managed to bring under his rule.

But the imperatives of nationalism required outrage in neighbouring countries, which Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar dismissed rather peremptorily. “Friendly nations have understood it,” he said, and while adding the needless dig, “Pakistan does not have the capability to understand it.”

Scrolling through the Twitter replies to Joshi’s Tweet threw up interesting insights such as this one from “Indian American Patriot”: “You don’t believe in this yourself and is unnecessary. Akhand Bharat would mean about 50 percent population of Indian will be non Hindus.” It does make one wonder if the Hindutva brigade has any plans to deal with that uncomfortable fact in an imagined “Akhand Bharat” as logic would follow such a domain would have to be devoid of all other religions, especially the Abrahamic ones.

For now, I will let the reaction from one Suresh Sharma to be the last word on this topic: “Cowards can't protect land from China and talk about Akhand Bharat. Fake pride by fake people.”

Maps and more maps

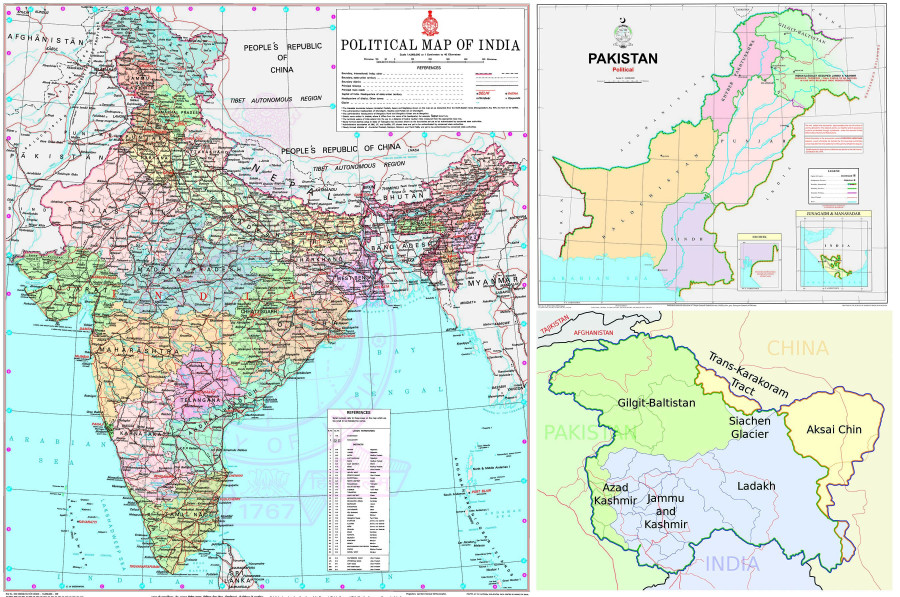

As someone who grew up with publications that almost always came from India—books and textbooks, maps and atlases, newspapers and magazines—the image of India was always one consisting of the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) standing tall above the rest of the country. It was only as a mature adult that I came across a map published in Pakistan. Despite being fully aware of the Kashmir dispute, it was with amazement that I looked at the part of north-western India with all of J&K firmly within Pakistan (and with the erstwhile nawabdom of Junagadh also thrown in for good measure). India looked like it had literally lost its head.

The maps of India and Pakistan presented here are the most recent ones from the websites of the Survey of India and the Survey of Pakistan, respectively. Despite both countries claiming J&K in its totality, in this version, the latter has fudged the eastern parts of J&K, marking it simply as “Frontier Undefined”, presumably because that area has been claimed by its close ally, China.

To aid the uninitiated, the Pakistani map also comes with the following notes: “Indian illegally occupied Jammu & Kashmir (Disputed Territory—Final Status to be Decided with Relevant UNSC Resolutions)”; “The red dotted line represents approximately the line of control in Jammu & Kashmir. The state of Jammu & Kashmir and its accession is yet to be decided through a plebiscite under the relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions”; and “Actual boundary in the area where remark FRONTIER UNDEFINED appears, would ultimately be decided by the sovereign authorities concerned after the final settlement of the Jammu & Kashmir dispute”. Given its global weight, India’s map simply shows all of J&K within its boundaries without recourse to any explanation.

Different reality

The reality as it stands is, of course, different. As presented in the third map, J&K has been carved up among India, Pakistan and China. That includes the area known as the Trans-Karakoram Tract that Pakistan ceded to China in 1963 (resulting, by the way, in three of Pakistan’s five 8000-metre peaks straddling the Pakistan-China border). Taken together with Aksai Chin controlled by China, the remaining consists of India-administered Kashmir (Indian-Occupied Kashmir, or IOK, for Pakistan) and Pakistan-administered Kashmir (Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir, or POK, for India).

At the same press meet where he defended the “Akhand Bharat” mural, Jaishankar said the goal of taking back POK from Pakistan remained unchanged. “As far as PoK is concerned, we have a very clear stand. And this is not the stand of just our government, but of the parliament and the entire country,” he said.

The learned minister would know very well the saying, “Possession is nine-tenths of the law,” as would his counterparts in Beijing and Islamabad. All the posturing is just that—performance for a domestic audience. That would also explain why when our government adopted a new map of Nepal some years ago, showing a stretch of land stretching outward from the north-westernmost tip of Nepal into an area under India’s control, not half an eyebrow was raised in New Delhi. Silence was the best way to ignore a wannabe but pesky antagonist neither in possession of the territory nor with any means to marshal the remaining one-tenth of the law. India knows how to live with different versions of a map. No matter what our nationalists say, it is only a matter of time before we will have to learn to do the same.

17.78°C Kathmandu

17.78°C Kathmandu