Columns

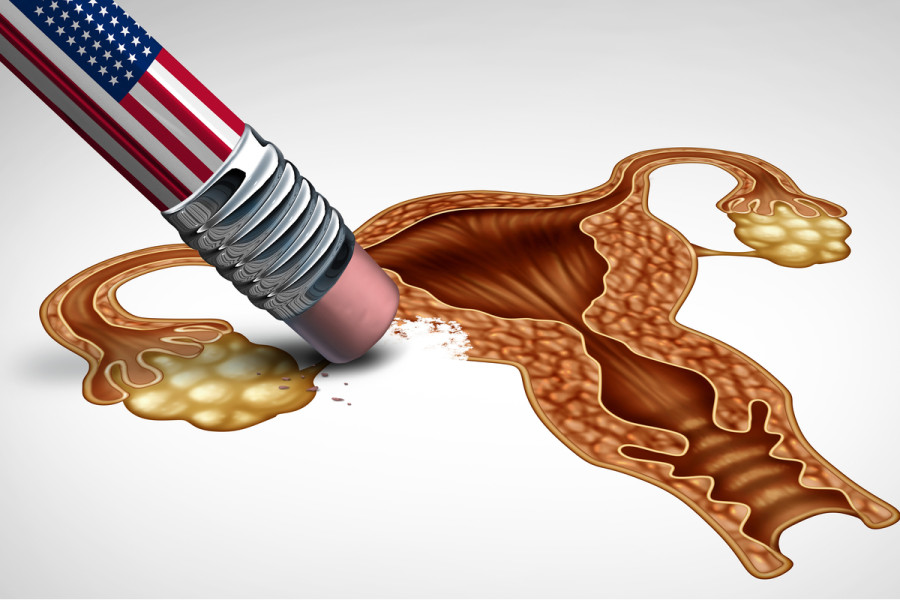

Abortion and democracy in America

Around the world, democratic legislatures have enacted laws on abortion that are liberal.

Peter Singer

Every woman should have the legal right safely to terminate a pregnancy that she does not wish to continue, at least until the very late stage of pregnancy when the fetus may be sufficiently developed to feel pain. That has been my firm view since I began thinking about the topic as an undergraduate in the 1960s. None of the extensive reading, writing, and debating I have subsequently done on the topic has given me sufficient reason to change my mind.

Yet I find it hard to disagree with the central line of reasoning of the majority of the US Supreme Court in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the decision overturning Roe v Wade, the landmark 1973 case that established a constitutional right to abortion. This reasoning begins with the indisputable fact that the US Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and the possibly disputable, but still very reasonable, claim that the right to abortion is also not implicit in any constitutional provision, including the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The reasoning behind the decision in Roe to remove from state legislatures the power to prohibit abortion was clearly on shaky ground. Justice Byron White was right: The Roe majority’s ruling, he wrote in his dissenting opinion in the case, was the “exercise of raw judicial power.”

The Supreme Court exercised that power in a way that gave US women a legal right that they should have. Roe spared millions of women the distress of carrying to term and giving birth to a child whom they did not want to carry to term or give birth to. It dramatically reduced the number of deaths and injuries occurring at that time, when there were no drugs that reliably and safely induced abortion. Desperate women who were unable to get a safe, legal abortion from properly trained medical professionals would try to do it themselves, or go to back-alley abortionists, all too often with serious, and sometimes fatal, consequences.

None of that, however, resolves the larger question: do we want courts or legislatures to make such decisions? Here I agree with Justice Samuel Alito, who, writing for the majority in Dobbs, approvingly quotes Justice Antonin Scalia’s view that: “The permissibility of abortion, and the limitations upon it, are to be resolved like most important questions in our democracy: by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.”

There is, of course, some irony in the majority of the Supreme Court saying this the day after it struck down New York’s democratically enacted law restricting the use of handguns. The Court would no doubt say that, in contrast to abortion, the US Constitution does explicitly say that “the right of the people to bear arms shall not be infringed.” But that much-quoted phrase is preceded by the rationale that “a well-regulated militia” is “necessary to the security of a free state.” The supposed right of individuals to carry handguns has absolutely nothing to do with the security of the United States, so a sensible application of Scalia’s comment on how the question of abortion should be resolved would have been to leave the regulation of guns to democratic processes.

There is an even more radical implication of the view that courts should not assume powers that are not specified in the Constitution: the Supreme Court’s power to strike down legislation is not in the Constitution. Not until 1803, 15 years after the ratification of the Constitution, did Chief Justice John Marshall, in Marbury v Madison, unilaterally assert that the Court can determine the constitutionality of legislation and of actions taken by the executive branch. If the exercise of raw judicial power is a sin, then Marshall’s arrogation to the court of the authority to strike down legislation is the Supreme Court’s original sin. Marbury utterly transformed the Bill of Rights. An aspirational statement of principles became a legal document, a role for which the vagueness of its language makes it plainly unsuited.

Undoubtedly, the US Supreme Court has issued some positive and progressive decisions. Brown v Board of Education, in which the Court unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, is perhaps the foremost among them. But it has also handed down disastrous decisions, such as its ruling in the notorious Dred Scott case, which held that no one of African ancestry could become a US citizen, and that slaves who had lived in a free state were still slaves if they returned to a slave state.

More recently, in Citizens United v Federal Election Commission, the Court invalidated federal laws restricting political donations, thus opening the floodgates for corporations and other organisations to pour money into the campaigns of their favoured candidates or political parties. And the decision on handguns seems likely to cost more innocent people their lives.

Supreme Court decisions cannot easily be reversed, even if it becomes clear that their consequences are overwhelmingly negative. Striking down the decisions of legislatures on controversial issues like abortion and gun control politicises the courts, and leads presidents to focus on appointing judges who may not be the best legal minds, but who will support a particular stance on abortion, guns, or other hot-button issues.

The lesson to draw from the Court’s decisions on abortion, campaign finances, and gun control is this: Don’t allow unelected judges to do more than enforce the essential requirements of the democratic process. Around the world, democratic legislatures have enacted laws on abortion that are as liberal, or more so, than the US had before the reversal of Roe v Wade. It should come as no surprise that these democracies also have far better laws on campaign financing and gun control than the US has now.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu