Columns

Round and round the wheel goes

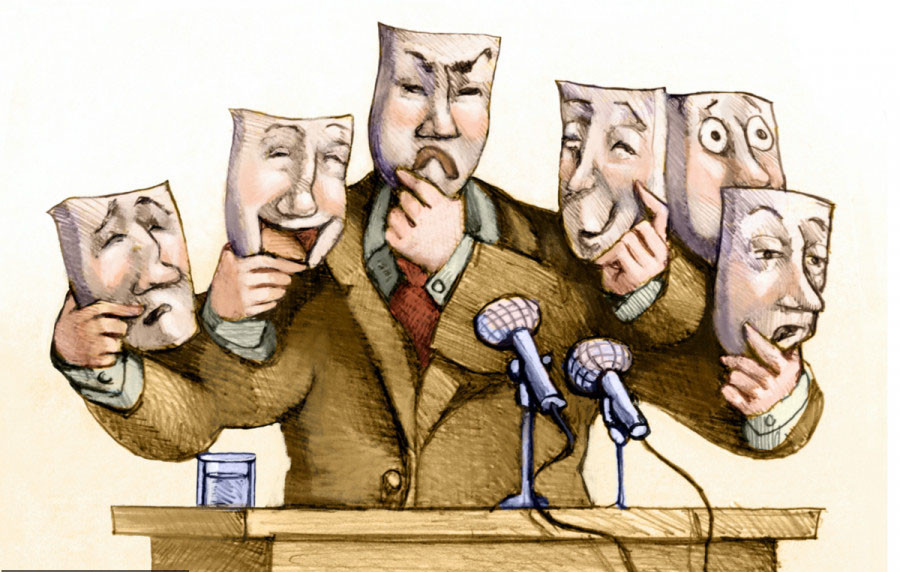

Why is Nepal stuck in a loop of musical chairs between the same old men?

Amish Raj Mulmi

And so, the Olifice has crumbled. Like all those who came before him, KP Oli too finds himself now labelled as former prime minister, and one hopes it remains so. Responsible for reviving Ram in Nepal, it was befitting that a vanar sena accompanied the boss of Balkot to his residence. Just as his stint in power, Oli’s oppositional politics has indicated it will be full of personal barbs and lack of morality. It remains to be seen whether his opponents will go down the same slope or not.

Oli’s politics has indeed been different from the many preceding prime ministers, but in his exit, he was the same as all others. For, he left office, and the country, in such a perilous state that the Nepalis have very low expectations from his successor, Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba (who is, by Nepali standards, a veteran in the post). All Deuba needs to do is steer the country through the pandemic without allowing political drama to overpower the general discourse until the 2022 elections. If he does so, Nepalis will look back at Deuba’s fifth stint at premiership with satisfaction.

Unfortunately, Deuba’s ship has already found itself in some choppy waters, with various leaders who’ve supported his coalition now demanding their own pound of flesh. One expects the coalition will last till the next elections because, frankly, the Nepali people are now left with no alternatives. We’ve checked out all the jogis, and not one of them delivered a modicum of stability and good governance.

So why is Nepal stuck in a loop of musical chairs between the same old men, and why can the Nepali people never get a full term of government? Nepal’s political instability has been the subject of countless books, so it is obvious that there are no easy answers. Nonetheless, for the sake of this column, let me offer my own thesis:

One of the defining factors of post-2008 Nepali politics is that no single party or ideology has been dominant enough to command a majority. The Nepali voter has swung between the three major parties in the last three elections. And although Oli commanded a two-thirds majority after the 2017 elections, the discord between Oli and Pushpa Kamal Dahal tells us the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) had never been a true unification but a loose alliance between the Maoists and the UML borne out of circumstances advantageous to both.

Because no single party can command a majority, our governments inevitably end up becoming coalitions where every leader expects a quid pro quo for their support to a government. However, because the pot itself is so small, whenever a leader attempts to overwhelm the alliance by inserting their personnel in key posts or providing no space to the other leaders, the alliance breaks up. As a friend explained more cogently, if 15 men drive Nepali politics, a government is formed whenever nine of them come together. But inevitably, three of the top leaders or their men gobble up the best ministries. The remaining six then approach the other six to topple the existing government and form their own. And so the wheel goes round and round.

Oli’s mistake was that he attempted to go it alone instead of sharing the top posts, lines of patronage, and resources with Dahal and Madhav Kumar Nepal. That would never work, because the UML was never a party that was loyal only to one leader, unlike Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party, which Oli tried to emulate. Instead, Oli succeeded in bringing almost all of his opponents together, and if there’s one thing Nepali parties are good at, it’s to align together against a common enemy.

Now that Deuba is in power, hopefully, till the next elections, the key questions still remain: Can anything be done to change this structural weakness of Nepali politics? The outcomes can vary, but there seems to be a consensus that Oli will employ a Hindu socio-religious agenda as a way to shore up the conservative vote, which can be a formidable force to match other progressive tendencies in Nepali polity. If that happens, we can expect a regression in Nepali society’s outlook, and further weakening of the federal republic.

Having said that, one must remember that elections alone will not be the solution to Nepal’s structural weaknesses of casteism and lack of representation, as seen in several instances in the recent past. Further, Nepal is currently in the middle of a demographic dividend, with 40 percent of its population in the 16-40 age group. But we have not been able to take advantage of it, and the lack of economic opportunities at home has driven the best of our talent abroad. The pandemic has further highlighted the gap in our societies, and unless an immediate correction happens to alleviate foundational weaknesses, Nepal will miss the bus once again.

Stability can bring optimism to society, as seen in the rush of economic activity during the two and a half years of NCP rule. Despite Oli’s autocratic tendencies, there was widespread belief that a full-term government would provide continuity and inject new momentum into the country. Now, Nepal is back to square one. The angst has returned, and the frustration of a youth population that is being left far behind the world is visible. The pandemic is here to stay for a few more years at least. The solutions are many, but all of them require political will. As for that, unless our leaders can accrue any benefits, the wheels will continue to turn as they always have.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu