Columns

How to ‘Make in Nepal’?

Implementation and government support will make or break the new industry campaign.

Achyut Wagle

The 'Make in Nepal-Swadeshi' campaign, launched earlier this year by the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI), is undoubtedly long overdue. The campaign aims to establish more than one thousand new industries and raise industrial sector contribution to 26 percent of the gross domestic product by 2030 from the current level of less than 14 percent. It also hopes to substantially generate employment opportunities and to expand the country's export to $5 billion annually in the next five years, from less than $1 billion now.

But, sadly, what could be said as a slip on the very first step, the tagline itself appears as an unimaginative imitation of the 'Make in India' campaign, initiated six years ago by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. It had planned to revitalise the economy, attract investment, and enhance the production and exports of Indian brands. In place of the lion silhouette used as the symbol of Make in India, CNI has proposed a one-horned rhino for Make in Nepal and has added the term swadeshi in the tagline.

Is it credible?

However, there are stark conceptual and structural differences between the Indian and Nepali initiatives in many respects, including ownership and planning—and even the seriousness of the campaign itself. The Indian campaign was entirely a government strategy focused mainly to attract foreign direct investment while the Nepali one is a half-hearted private sector initiative. This difference in 'ownership' of the whole programme is bound to have a telling effect on the speed and expanse of required calibrations on legal and institutional arrangements critical for the implementation of the same. Governments like ours, more often than not, are unforthcoming to facilitate purely private sector initiatives like this. The private sector always at the receiving end of the government's economic priorities and policy regime may rarely be able to adequately overcome the hegemony so as to enact much-needed investment-friendly legislation, undertake market research and consolidate economic diplomacy for international outreach.

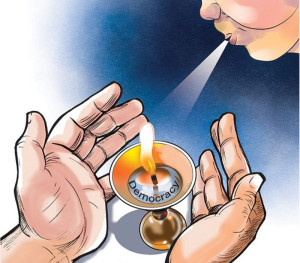

In theory, the importance of initiatives like Make in Nepal from the private sector can hardly be overemphasised while the country's political leadership appears completely insensitive to address pressing economic issues. Nevertheless, the haste of unveiling ambitious programmes like this even without identifying the focus areas for investment and production and, of course, without proper planning and coordination among the critical stakeholders have the risk of it turning out to be only a short-lived media or political stunt. Even for its marginal success, this programme in the first place needs national ownership and a clear roadmap for efficient execution. The launch of Make in Nepal does not seem to have affirmatively ignited that psyche of national ownership and credible atmosphere for its implementation.

Myth of manufacturing

In Nepal's case, the story of industrialisation and augmenting the manufacturing base has always remained something of a big hoax. All sub-sectors of manufacturing, with a few exceptions of agro-processing industries, completely lack what is called the domestic backward linkage in the production ecosystem. In the inaugural speech of the Make in Nepal, Prime Minister Oli very aptly remarked that the production of our iconic products like Bhadgaule topi are dependent on imported thread, dye and stitching needles. The same applies to our Palpali or Purbeli Dhaka fabric production, which we consider a pure Nepali brand. In the sectors like pharmaceuticals, pashmina, shoes and readymade garments now claiming to be booming, all the raw materials used are imported. Looms and pieces of machinery—and often skilled manpower—come from neighbouring countries.

Actual value addition within Nepal is very marginal; generally below eight to ten percent. Fishery, dairy and poultry farming, breed, feed and medicines must rely on outside supply. Even for traditional vegetable and food grain produce, farmers depend almost entirely on imports of seeds, fertilisers and pesticides. In handicrafts like silver jewellery, which Nepal claims to be one of its main export items, the country depends on imports not only for silver metal but all chemicals and artisans. Therefore, claims of Nepal soon becoming independent in many of these products is grossly misleading. Such unsustainable and essentially uneconomic methods of production have both comparative and competitive disadvantages that amply explain the low level of industrialisation, low job creation, small industrial contribution to the GDP and, in turn, chronically dismal economic well-being.

Charting a roadmap

There is no reason to thwart or discourage the initiative that at least has begun. At the same time, the reality must also be accepted that innumerable structural, legal and operational issues first need to be addressed in order to translate the idea of 'making' into an actual product.

First, attracting a substantive amount of investment is the biggest challenge. Nepal has never been a priority destination for large-ticket foreign direct investment (FDI). The FDI stock so far is barely 6 percent of the GDP. The actual realisation rate of commitment is less than 30 percent. Let alone big foreign investors, a $100 million investment fund proposed by the non-resident Nepalese also has not materialised, even a decade since being committed. The capacity of the Nepali financial system, comprising of banks, mutual funds and venture capitals aggregated, is very limited. How the government wants to promote and participate will remain very critical.

Second, the ability to prioritise fewer viable products, specifically the ones with adequate backward linkages that can utilise domestic labour, will only make the endeavour manageable and result-oriented. For now, three key areas of production have a realistic prospect of better value addition through backward linkages, import substitution and local employment generation. One, in agriculture and domesticated animal input-based productions. Two, in earth-based construction material industries including cement, stone, sand etc. Three, in mines and mineral-based industries, which largely remains untapped in Nepal.

Third, in light of the fact that Nepal has historically failed both in the branding and marketing of her own products, a serious consideration for brand positioning and systematic market exploration, primarily in neighbouring countries, must be an integral part of the Make in Nepal campaign. The emotional component of encouraging the citizens to use swadeshi will work for brand-conscious consumers only if our products can compete in quality and price. The import substitution of even daily consumables is impossible without making the products readily available in the markets spread far and wide within the country. Good luck, Make in Nepal!

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu