Columns

Self-quarantine, Kathmandu style

The tradition was given up in the 1960s after the old Tibet trade came to an end.

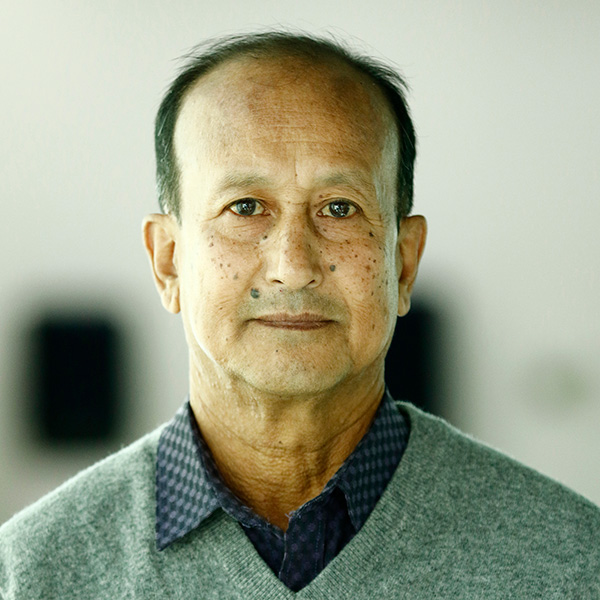

Kamal Ratna Tuladhar

When my father returned from Lhasa in 1954, he didn't go bounding up the stairs to hug his dear family members, whom he had not seen for six years. In fact, he wasn't even allowed to go higher than the first floor, much less touch any of the people in the house. For the next five days, he slept alone in a spare room. The kitchen was off-limits to him, and he ate separately while the rest of the family had their meals sitting down together on a long mat. My father had to wash the dirty dishes himself too. Such was the cultural practice among Newar merchants returning home from Tibet in those days.

Since the traders had journeyed in faraway lands and consorted with people from unknown places, they could have been contaminated—both spiritually and physically. So, custom required that they keep social distance until they had completed the stipulated rituals to cleanse themselves. The practice is known as nee chwanegu in Nepal Bhasa which, in today's parlance, would be called self-quarantine.

People were reminded of this ancient rule in the Kathmandu Valley after everyone began talking about isolation and quarantine following the novel coronavirus outbreak. Renewed interest in this half-forgotten tradition has also sparked a debate whether it was a precaution to prevent the transmission of infectious diseases, or state-imposed social behaviour intended to assert the domination of the ruling classes.

Not all returning travellers had to practice nee chwanegu. People coming back from India were exempt from this rule, except for being made to drink chiretta brew for its anti-malarial properties, as the disease was endemic in the hot southern plains. They did not need to obtain any paperwork from the government allowing them to rejoin society either. But returning Lhasa merchants, after finishing their isolation period, had to obtain a piece of paper saying that they had 'got their caste back', which they had supposedly lost during their journey across the Himalaya. The paperwork, some say, is evidence of discrimination by the state against travellers to certain regions.

The cultural practice of nee chwanegu had been loosened a bit when my father returned from Lhasa in 1954. It was not as strict as in the old days, when merchants would self-isolate for 15 days outside their home. Now, you could stay in your own house. The isolation period, too, had also been shortened. Society had devised an imaginative arrangement under which family members could share the mandatory isolation period. When my father underwent nee chwanegu, my mother and aunt also observed the prescribed rules, and so he had to self-isolate for only five days—the two women each fulfilling the obligations concurrently for five days on his behalf. They had only one meal a day and took a daily bath. A day before the concluding ceremony, they were forbidden to eat anything.

The family priest came to the house to conduct a Buddhist service. Each person sat on the floor facing sand mandalas representing the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. The mandala is made of limestone powder using a wooden mould. The wood has grooves cut in it in the shape of the mandala. The grooves are filled with limestone powder, and the mould is placed face down on the floor. A few taps on the wood makes the limestone powder fall on the floor, creating the mandala. As the priest chanted from sacred texts, they lighted butter lamps and placed flowers on the mandalas. The ritual concluded with a feast for all the relatives. Now my father was purified, and he could mix with other people and resume normal life.

My father belonged to a thousand-year-old tradition of Lhasa Newar merchants. Going to Tibet and running the ancestral shop there was the karma of all the men in the family. They rotated between Kathmandu and Lhasa every so many years. The journey by mule caravan across high mountains and barren plains lasted almost a month. And every time one of the brothers returned from Tibet, he had to self-isolate and perform the rituals.

The nee chwanegu system is said to go back to the Malla period, when the Tibet trade reached a peak. A fine evidence of those glory days is the community hall at Asan in central Kathmandu, which doubled as a holding centre for returning traders. The ceremonial square and vibrant bazaar straddles the trade route to Lhasa that traverses the Kathmandu Valley—one reason why it should come as no surprise that the Tuladhars, key players in the Tibet trade, have their ancestral homes here. Yita Chapa, the community hall, encloses the market square on the southern side. Oldsters recall that Tibet-returned merchants would self-isolate here for 15 days before re-entering their homes. There was a sunken water spout on the street leading into Asan, next to the city gate which only remains in oral history. The traders would bathe under its gushing water and make themselves presentable before stepping foot in the city.

Living in close quarters in densely packed neighbourhoods, the highly urbanised Newars developed the practice of self-isolation to prevent the spread of infectious diseases; it continued down the centuries into modern times. The tradition was given up in the 1960s after the old Tibet trade came to an end. With the coronavirus continuing its worldwide rampage, people are recalling the ancient system of self-isolation. Only a few of the Lhasa Newar merchants who observed the cultural practice are still living. My father Karuna Ratna Tuladhar passed away in 2008 at the age of 88. If he were still around, I am sure he would say that it makes a lot of sense.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu