Columns

Unshackle knowledge creation

Nepal Health Research Council must not stand in the way of the country’s contribution to the global knowledge base on Covid-19.

Dr Kiran Raj Pandey

As unprecedented as the global suffering and devastation wrought by Covid-19 has been, equally swift and unprecedented has been our collective response to understand the disease. Scientific knowledge and data are being created and shared with a previously unseen ferocity. Nepal can’t be left too far behind.

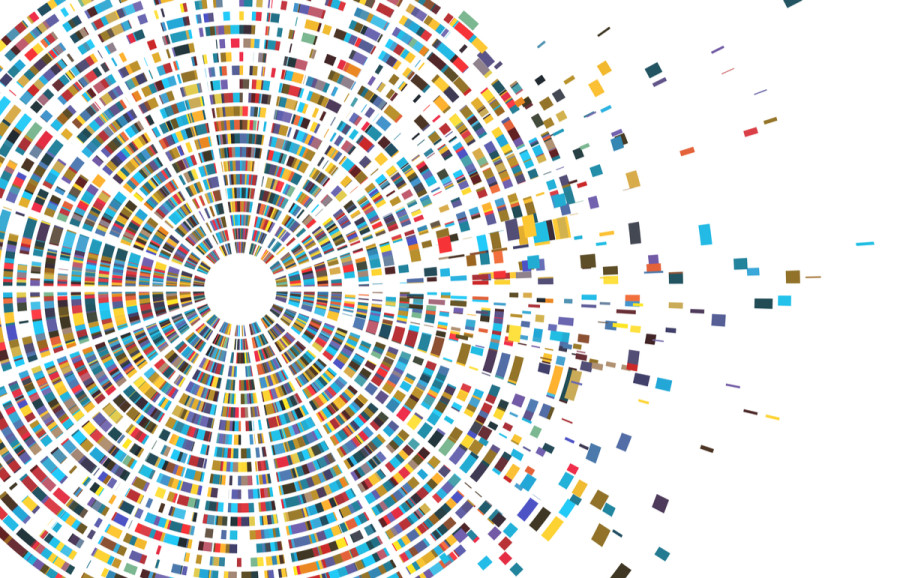

The sharing of SARS-CoV-2 genomics data is illustrative. In early January 2020, scientists in China called Peter Bogner, the founder of an influenza virus data-sharing platform named GISAID (Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data) to ask if the platform would be willing to host and globally share genomic data on a newly emerging coronavirus. Bogner readily obliged, and thus the first genomic sequence of the as-yet-unnamed novel coronavirus became publicly available through GISAID’s platform.

Since then, we have about 30,000 genomic sequences of that virus, now named SARS-CoV-2 virus, available through GISAID. This is unprecedented.

Public announcement

Back in 2002-03 when the first SARS coronavirus outbreak occurred, it took a year to sequence the viral genome. This time around, there are reports that the genome may have been sequenced within a few days after a cluster of cases of pneumonia of unknown cause were reported in Wuhan in late December. On January 7, Chinese scientists publicly announced that they had identified a novel coronavirus responsible for the pneumonia outbreak. The call to Peter Bogner followed around the same time. This was a month before the virus—or the disease it caused—even had a proper name.

Within a short while after the novel coronavirus was announced, German scientist Olfert Landt got down to making a test for this virus. Landt had 30 years of experience working with coronaviruses; two days later, on January 9, he readied a few tests that were likely to work against this new coronavirus. A validated test for the new virus then became available right after Chinese authorities made the viral genome available on several public domains, including at GISAID.

The possibilities with such freely available genomic datasets don't end with tests alone. A global initiative called Nextstrain is using this genomic data to create family trees of the various strains of SARS-CoV-2 that are circulating across the world. Nextstrain’s work has immense potential to help tailor our efforts to control the pandemic. Some others have used the genomic data to study the affinity of viral proteins against human tissue signatures called HLA (Human Leucocyte Antigen). HLAs are somewhat like blood groups and can offer us vital clues on whether susceptibility patterns against the virus are different among people.

Others are using this genomic information to study viral proteins that could be targeted by drugs. Not to mention the more than 100 vaccine initiatives that are ongoing around the world right now. Designing and deploying a safe and efficacious vaccine will require information on the strain of the virus that is prevalent in an area.

Since the first genome, more than a thousand genomic sequences are being deposited in the public domain every week. The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York alone contributes more than a hundred SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences a week. Countries from all corners of the world are sequencing and contributing viral genomes; India has contributed about 200 sequences thus far. Bangladesh has shared many as well. Nigeria and Ghana have sequenced viral genomes on their own. Nepal has contributed one genome, sequenced at the WHO supranational referral lab at the University of Hong Kong.

The global response to overcome Covid-19 is proving to be health sciences' Manhattan Project. More than 20,000 scientific papers and manuscripts have already been written on the topic. And while countries around the world are doing everything they can to contribute to this global response, we in Nepal aren’t terribly helping our own cause. The brouhaha surrounding ethical approval for the sequencing of the Nepali virus sample in Hong Kong is a case in point.

Whether or not researchers erred in failing to obtain ethical approval before the viral genome sequencing is a matter of debate. Ethical approval committees in various jurisdictions differ in their approach in this regard. Section 7.7 of the National Ethical Guidelines for Health Research (2019) published by the Nepal Health Research Council outlines provisions for human genetics research, but there are no specific recommendations for viral genomics studies. Assuming recent enforcement actions against the researchers were made in good faith, the arguments put forward by the Nepal Health Research Council do not stand up to scrutiny. Enforcement actions, when poorly conceived, can be counter-productive.

The Nepal Health Research Council’s claims that genes could be maliciously patented are misinformed; first, SARS-CoV-2 viral genomes from all over the world—30,000 and counting—have been made available in the public domain. It is hard to patent something that is freely available in the public domain. Second, the entity sequencing the viral sequence was not a private for-profit company, rather a university-affiliated lab and a WHO referral centre with an existing protocol for sample transfer from the National Public Health Laboratory. Third, based on international case law, any attempt to patent naturally occurring genetic sequences won’t stand legal scrutiny. For example, the Supreme Court of the United States has unanimously ruled that naturally occurring genetic sequences can’t be patented. Fourth, any polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based test, for which consent was presumably granted, is essentially a genomics study; a PCR test reads a small section of the viral genome, a genomic sequencing reads the entire viral genome.

While the Nepal Health Research Council does have the right to question the ethical conduct of research within its jurisdiction, that does not absolve it of its obligation to facilitate an environment for research in the country, especially at a time when any new information we can learn about this pathogen has the potential to save thousands of lives. Already, at a time when there has been an extraordinary explosion of knowledge creation on Covid-19 around the world, we are lagging behind. This can cost us dearly.

Research regulation

A well-reasoned consideration of the risks and benefits of knowledge creation is at the heart of responsible research regulation. Regulatory bodies in many countries have come up with emergency directives that expedite or entirely waive approval processes when appropriate. In countries with the most productive knowledge creation environment, regulators attempt to facilitate, and not stifle, research within their jurisdiction while ensuring ethical conduct of such research. Regulation must get in sync with international best practices.

Given an enabling environment, viral genomic sequencing is something that can be done in our country. If our neighbours can do it, so can we. The technical capacity exists here. Instead, if we stifle local production of knowledge with desultory arguments, not only will we not be contributing to the global body of knowledge in the fight against Covid-19, but also will have lost our moral authority to demand the fruits of that knowledge—drugs, vaccines and other advances—when they become available.

The world will do just fine without Nepal contributing to the global body of knowledge on Covid-19. Nepal, however, won’t.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

16.88°C Kathmandu

16.88°C Kathmandu