Books

There’s no good and bad genre, only good and bad writing

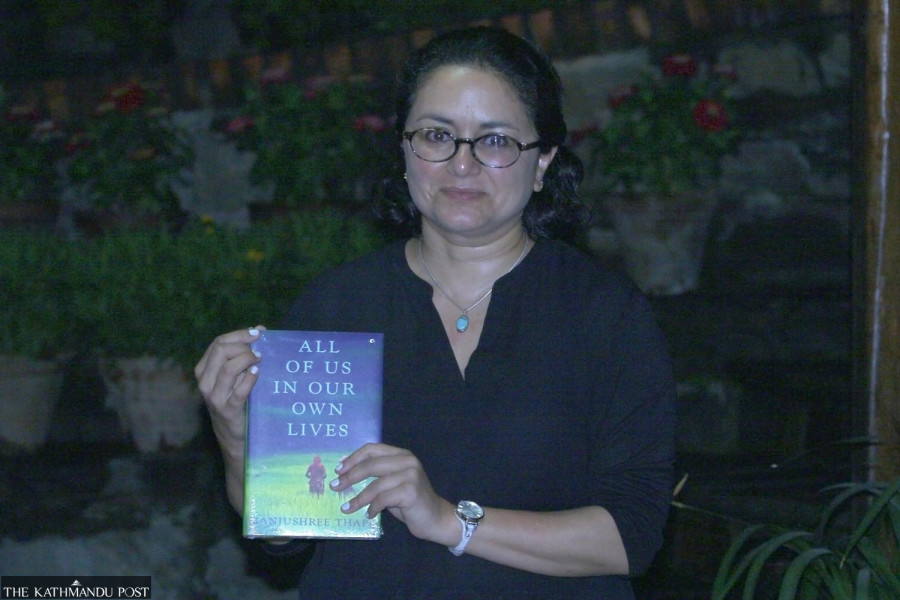

Manjushree Thapa discusses her distinguished writing career, challenges in the publishing industry and her ongoing exploration of prose.

Manushree Mahat

Manjushree Thapa’s writing has taken many tours through fiction, nonfiction, translations and biographies. Unbound by the constraints of genre, she is committed to the art of writing and continual improvement.

Among her notable works are ‘Forget Kathmandu: An Elegy for Democracy’, ‘All of Us in Our Own Lives’, ‘The Tutor of History’, and the English translation of Indra Bahadur Rai’s ‘Aaja Ramita Chha’, ‘There’s a Carnival Today’.

In a conversation with Manushree Mahat of the Post, Thapa reflects on her distinguished writing career, sheds light on the challenges within the publishing industry and discusses her ongoing exploration of prose.

How did your reading journey begin? How has it been taking shape over the years?

My reading journey began early in life during my childhood in Canada. I had access to numerous English-language children’s books, and our home had a rich collection. I started delving into literary heavy books at a young age, exploring British and Russian classics and various other works by the end of college.

As I started writing, I realised there were significant gaps in my knowledge on some topics. To address this, I initiated reading projects. In one year, I focused on Chinese literature, followed by Mexican literature the next. Over the last two years, I’ve immersed myself in memoirs, particularly as my father’s memoir was in progress. Much of my reading revolves around expanding my understanding of the world and literature, contributing to my own writing journey.

Having ventured into fiction, nonfiction, biographies and translations of renowned authors, which genre do you find yourself drawn to the most?

My writing journey began with nonfiction, and I’ve realised that it remains my fundamental impulse—a documentary impulse. Even my subsequent fiction novels lean towards realism. So, nonfiction is the foundational genre that has influenced all my other works.

When it comes to your fictional works, like ‘All of Us in Our Own Lives’, they often revolve around characters. Stephen King suggests letting characters take their own course in writing. Is this your approach as well?

Certainly. The essence of writing fiction lies in delving into the inner lives of characters. Unravelling the layers of who they are allows us to explore our own humanity and inner worlds. The more fiction I write, the more I expand my understanding. Comparing my first fiction novel to my latest, ‘All of Us in Our Own Lives’, there’s a significant contrast in the depth and growth of characters—a crucial aspect of their stories.

How do you feel about the division of literature into high and low genres?

I recently came across an article in The Guardian discussing the problematic nature of segregating literature into genres. I believe it’s not the writers but the publishing companies and their marketing roles that impose these classifications. Critiques should focus solely on the quality of the writing rather than demeaning entire genres. For authors, genre is a secondary concern, more relevant to the marketing strategies of publishing companies.

There’s often discussion in the writing community about the necessity of pursuing a degree in creative writing or literature, given that writing is not always a lucrative or stable career. What’s your take on this?

Like any humanities discipline, creative writing and literature degrees aim to enhance your critical thinking, imagination and overall understanding of the human experience. I find this aspect crucial.

However, making a living solely from writing can be challenging. It’s essential to be practical about your career and future while also exploring opportunities to broaden your writing horizons. If pursuing a full-time creative writing degree puts you in financial strain, I recommend reconsidering. Starting your writing career under economic pressure can be limiting and joyless. During my writing journey, I supported myself by working at NGOs a lot of the time. It’s vital to safeguard the art; if excessive economic pressure stifles creativity, one should reconsider their choices.

How does it feel to handle someone else’s writing?

I enjoy translation; it has significantly influenced my own writing. The process of translating mirrors what you do with your original writing. When I started translating, I delved into Nepali literature, exploring classics and works by established writers and then moving on to contemporary writers. This experience taught me two things: how to portray Nepal in English and how to convey Nepali reality in the English language. It provided me with a sense of the social milieu to write about. At that time, there were only a few Nepali writers who wrote in English, and I realised that my writing aligned with contemporary authors, contributing significantly to establishing my place as a Nepali writer.

Could you share your experience with the Nepali publishing industry?

My first book, a travelogue titled ‘Mustang Bhot in Fragments’, was published by Himal Books. While they produced excellent books, their marketing efforts were lacking. They prioritised the quality of books. The second book, ‘The Country is Yours’, was published by Deepak Thapa’s private publishing house, which also produced really good books, but faced similar marketing challenges. Since then, I haven’t published books through the Nepali publishing industry myself. However, I observe a positive trend with more companies becoming ambitious and competitive in publishing, indicating a promising development in the industry.

In one of your articles, you talked about addressing the concerns of a target audience. Do you still worry about the audience when you write, or do you focus on creating novels that you personally enjoy?

I believe this holds true for most writers and literary authors; you write the kind of books you want to read. The responsibility of considering the target audience often falls on the publishing companies. Now that I’m in Canada, it’s challenging to find the same interest in South Asian literature. My focus remains on South Asia and the audience here. I concentrate on refining my craft and the creative writing process rather than dwelling too much on the audience.

I recently discussed prose and narrative style with another author. The use of first and third-person narratives can be an interesting choice. Why do you prefer the third person?

For me, the first person poses challenges in terms of voice. I initially wrote my first fiction novel, ‘Seasons of Flight’, in the first person because there was only one perspective. However, I soon realised that it didn’t work, and I changed it to a third-person narrative, which effectively captured the character’s inner voice. In a first-person narrative, you must convey the world through the character’s authentic voice. This reminds me of Kazuo Ishiguro’s ‘Remains of the Day’, a technically proficient novel told through first-person narration. When the main character begins to lie, readers understand that the character is being untruthful, which is a difficult feat. The novel I’m currently working on is written in the first person, so we'll see how that unfolds.

Manjushree Thapa’s book recommendations

Ducks

Author: Kate Beaton

Year: 2022

Publisher: Drawn and Quarterly

I’m not familiar with the graphic book format, but I enjoyed reading ‘Ducks’. I loved how it doesn’t follow a linear story and has great visuals.

The Ecological Thought

Author: Timothy Morton

Year: 2010

Publisher: Harvard University Press

This is a book I wish I had read when it was first released. The concepts of entanglement and the uncanny explored in this book are thought-provoking.

We Don’t Know Ourselves

Author: Fintan O’Toole

Year: 2021

Publisher: Head of Zeus

Exploring the history of Ireland, Fintan O’Toole’s ‘We Don’t Know Ourselves’ is a fascinating and remarkable account of modern nation-building. It details the astonishing journey of Ireland as a country.

Priestdaddy

Author: Patricia Lockwood

Year: 2017

Publisher: Riverhead Books

Patricia Lockwood’s memoir is fun to read. It details her life as she and her husband find themselves living in her father’s rectory due to financial troubles.

Arctic Dreams

Author: Barry Lopez

Year: 1986

Publisher: Charles Scribner’s Sons

While focused on the Arctic, this book prompted me to think about the myths that animate the land I was walking through on my trek to the Makalu Base Camp.

23.83°C Kathmandu

23.83°C Kathmandu