Books

Reading shapes my worldview

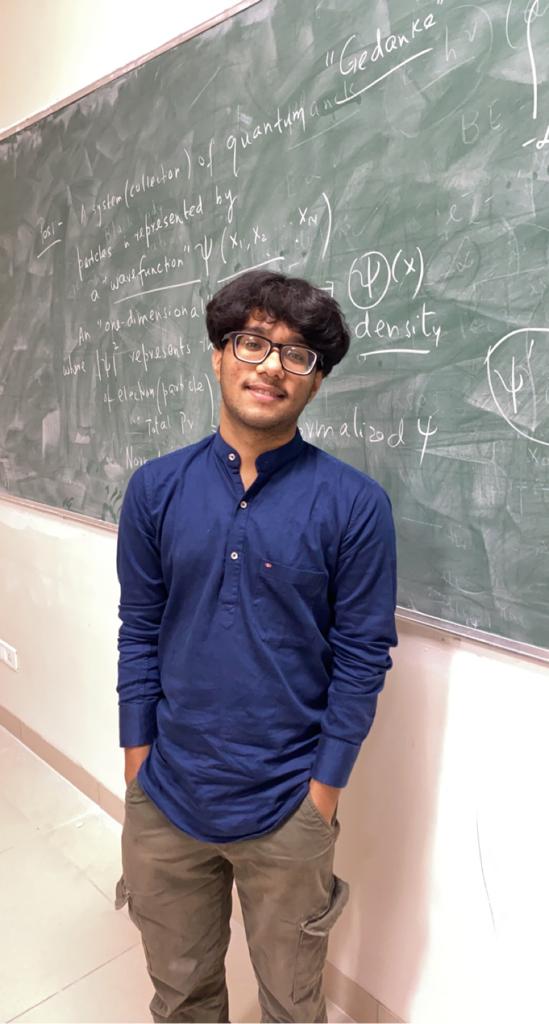

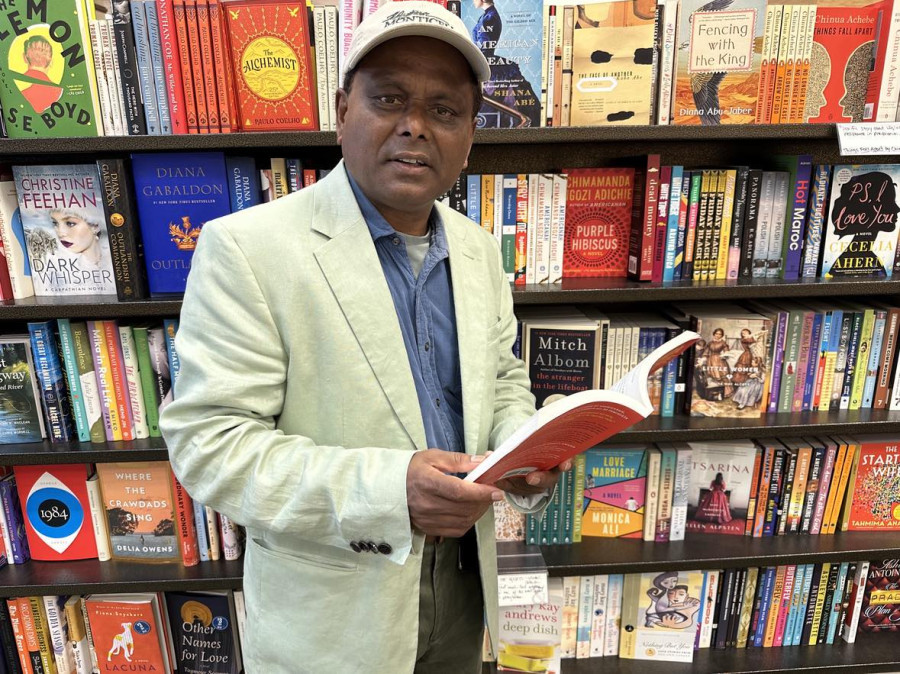

Pramod Mishra, researcher and professor of English, discusses his reading habits, literary inspirations and experience with local texts.

Kshitiz Pratap Shah

Professor Pramod Mishra teaches English at Lewis University in Illinois, USA, and has a PhD in English literature and theory from Duke University. He taught English for several years in Nepal before going to the US. Besides his academic writings, he wrote a regular column for The Kathmandu Post from 2009 to 2021 under ‘Crossroads’. He also writes occasional pieces in Nepali for Kantipur and in Rajbanshi for Kochila Samaad.

In this interview with the Post’s Kshitiz Pratap Shah, Mishra discusses his reading journey and experiences with texts in many local languages in Nepal.

When did you start reading? Do you remember your first read?

I started reading when I was four years old. The Hindi book ‘Manohar Pothi’ was my first read. Back then, books in Nepali were not available in my village. I remember reading about Gandhi as our Bapu.

Then the second book I remember reading was ‘Mahendra Mala’ in second grade. I remember it because this book was about a good boy, Binod, who always did the right thing. But reading that book, I felt that I was a bad boy. I never did anything right at that age. Binod was neat and clean, whereas I always got soiled playing in the village dirt. Binod completed his homework; I never did. His handwriting was beautiful; mine was terrible, and so on.

And then I stumbled upon a thick book called ‘Sukh Sagar’ the narrator of which was Sukdeo Muni. His stories of demons and gods, and his personality changed my life.

How have your readings inspired your academic works and writings?

My readings have made me who I am. Without my reading, I would just be a bundle of flesh and bones, nerves and sinew. My readings in English, Sanskrit, Hindi, Nepali and Bengali broadened and deepened my mental horizon. They gave me confidence and helped me understand the world—my place in the universe and society—better.

Coupled with my life experiences, readings gave me what in German is called weltanschauung, my worldview. They have made me an academic, one who looks at things in all their complexities with focus and depth in terms of time and space.

For many years, I didn’t write anything; I had no confidence in saying things that I wanted to say. But because of my accumulated readings, I gradually gained confidence and began writing. I still remember the lines from the Sanskrit animal fable, the ‘Panchatantra’, whose lines say, “Listening (reading) this story will make your speech (writing) unique everywhere besides offering you life lessons.”

What kinds of books do you like reading? What are you reading currently?

Well, for my work, I mostly read literary and scholarly works about literature and literary and cultural theory. But because of my interdisciplinary training in graduate school and wide-ranging curiosity, I read all kinds of books from various disciplines, from both scholarly and trade publications.

I am interested in novels, poetry, history, anthropology, sociology, psychology and so on. So, I read both fiction and non-fiction in multiple genres and disciplines and formats. I use Kindle, listen to Audible and get physical books. If you come to my house, you will find books in my study, car garage, basement and everywhere and anywhere. Sometimes, I feel one day, my books will kick me out of my house because of space constraints.

I am currently reading Salman Rushdie’s ‘Victory City’ and Sardar Bhim Bahadur Pandey’s ‘Tes Bakhat ko Nepal’.

What is a book that had a lasting impact on you?

At various stages of my life, different books have impacted me in specific ways. I mentioned the impact of ‘Sukhsagar’ earlier when I was seven years old. Later, while studying in India, I came across Jimmy Carter’s autobiography, ‘Why Not the Best?’ This book gave me encouragement and confidence at a time of severe financial difficulties and discouragement.

While finishing my studies in India, I discovered Bertrand Russell’s books—two in particular, ‘Introduction to Philosophy’ and ‘Conquest of Happiness.’ They gave me the courage to go through my twenties and thirties.

When I came to the United States, I kept three books by my bedside for years—Richard Wright’s autobiography, ‘Black Boy’, and Maxim Gorky’s ‘My Childhood’ and ‘My Universities'. Wright’s and Gorky’s books particularly helped me to channel my anger.

How do you differentiate between reading for academic or research purposes and reading for leisure? What kind of mindset change is there, if any?

When I read for academic purposes, I am slow and deliberate, working through a text, underlining, circling, taking notes, and writing in the margin if I own the book. I call this process “making it dirty.” I call this kind of reading “deep reading.” I look for keywords and ask the “WH” questions—who, what, where, when, how and whom. I read with the rhetorical situation of the book in mind—the writer’s credibility and background, the audience, the purpose, and the context in which the book was written. I look for the claim the writer is making about an issue in the book; the quality of the argument. I skim through the preface, the introduction and the conclusion before determining if I should read it more slowly and deliberately.

Reading for pleasure is what I call “beach reading.” I use multiple formats—digital, audio and physical book—for this purpose. In this case, I read both for the content and the beauty of language. If the language doesn’t give me pleasure, I quit.

What has your experience been in reading texts in various local languages of Nepal?

It has not been very good so far for several reasons. For one, there are not many written works available in local languages in which I have competence save for Maithili. I have read ‘Vidyapati’, but that’s more in bits and pieces and more in listening to his songs. Much of written Maithili suffers from two problems—its political marginalisation in both Nepal and India and its traditional stilted linguistic form valorised by the elite. This Maithili is distant from the masses and lacks the vigour and lifeblood needed to sustain and popularise it. These twin problems have formed a vicious circle.

Politically marginalised, Maithili could survive only in the hands of the elite, who kept it alive for identity and pride. When the written language remained confined as a hobby of the elite, it reflected their erudition and highbrow social and linguistic status, the problem that has plagued Sanskrit, for that matter, in all its history.

I have just begun writing in Rajbanshi because a quarterly magazine has just been launched in Jhapa by a Nepali language journalist Atmaram Rajbanshi. But without political empowerment in the form of use in government offices and public service commission, the talk of lifting the local languages will amount to only lip service. Look at the Nepali language, which I love and use widely. Because of political protection, patronage and use, the language that was a mere dialect a century ago now commands a vibrant literature and an ever-widening readership.

Pramod Mishra’s book recommendations

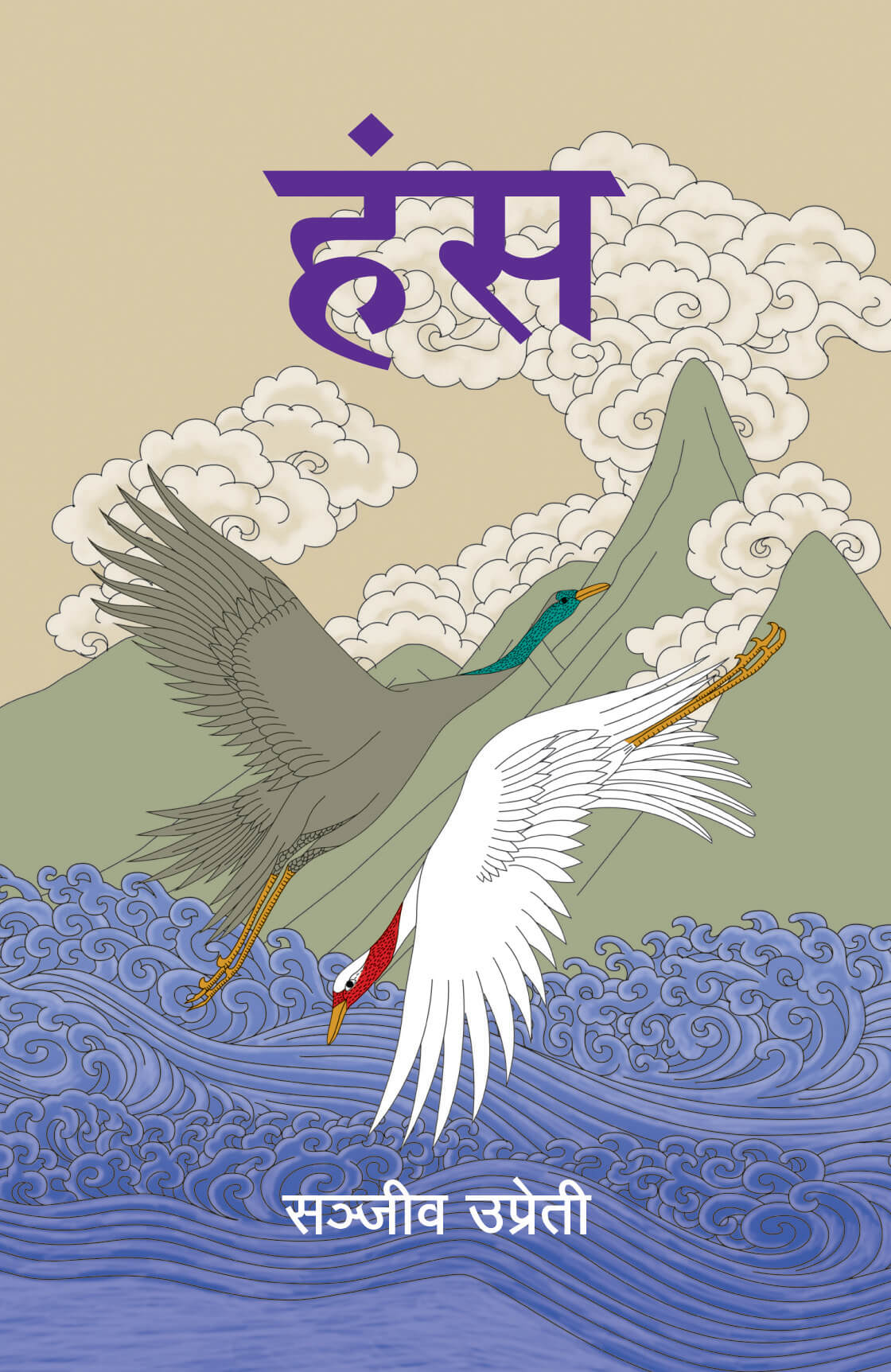

Hansa

Author: Sanjeev Uprety

Year: 2019

Publisher: Book Hill

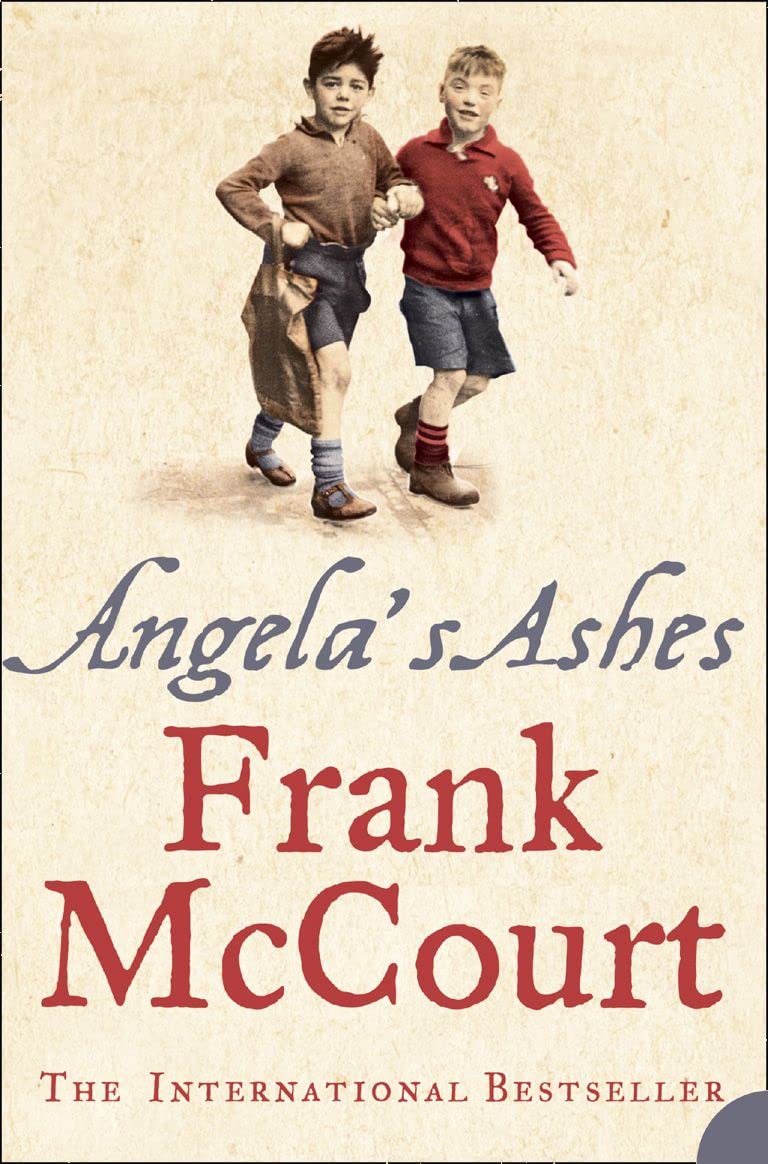

Angela’s Ashes

Author: Frank McCourt

Year: 1996

Publisher: Scribner

A House for Mr Biswas

Author: VS Naipaul

Year: 1961

Publisher: André Deutsch

Selected Poems

Author: Seamus Heaney

Year: 2014

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Gitanjali

Author: Rabindranath Tagore

Year: 1910

Publisher: Macmillan and Co Limited

The God of Small Things

Author: Arundhati Roy

Year: 1997

Publisher: Random House

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu