Books

Reflections of an administrative and a civil society rebel

The book features the many travails and tribulations that Pandey has faced in his life.

Madan Kumar Bhattarai

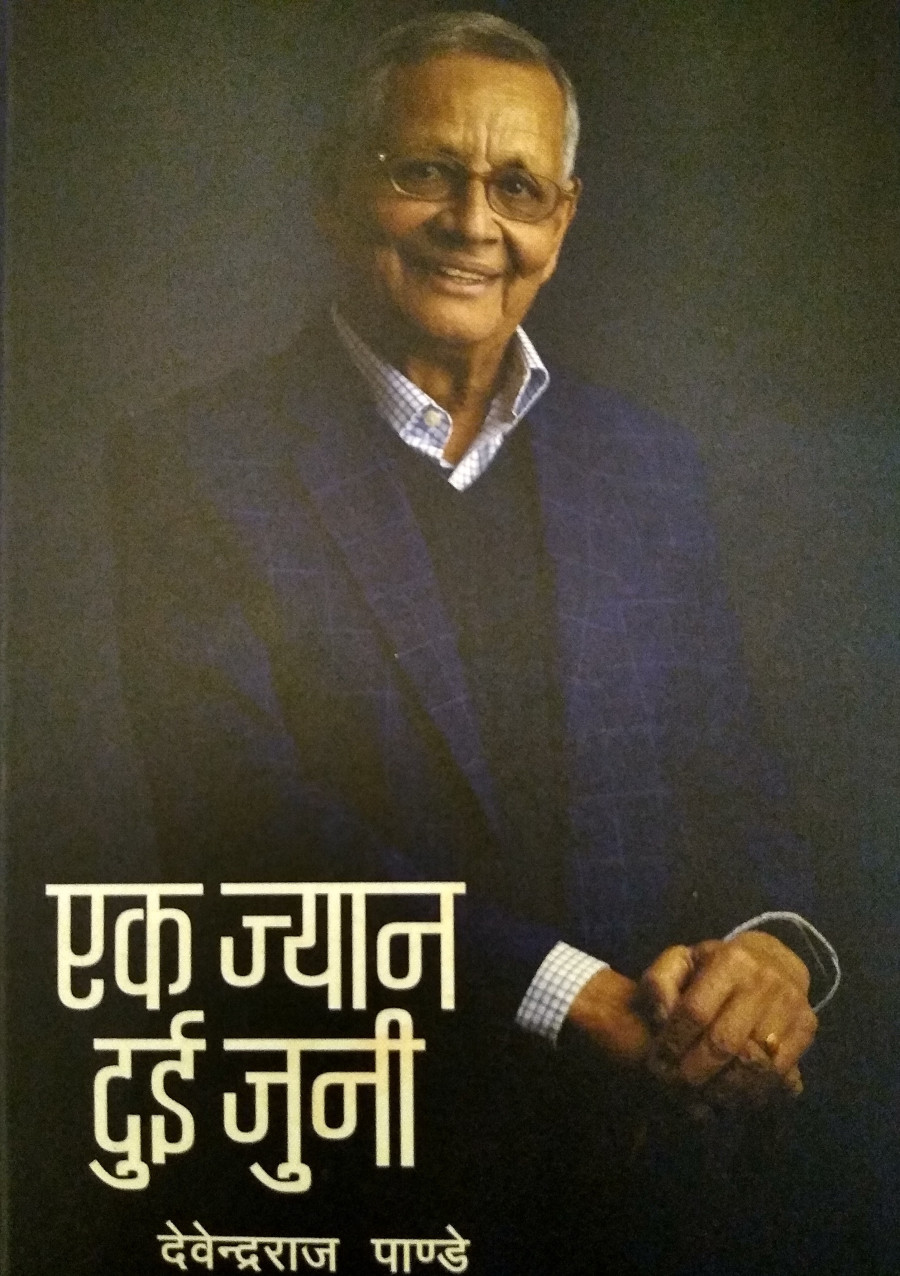

On the front cover of Devendra Raj Pandey’s book ‘Ek Jyan Dui Juni’, which can be roughly translated as ‘one body with two lives’, is an attractive portrait of the author. Pandey is a former senior civil servant and an intellectual. The book has ten chapters, but it can be divided broadly into two parts—the first part covers his life as a civil servant, and the second part deals with the rest of his life during which he took up many roles from a self-declared troubleshooter for the restoration of democracy, a civil society leader to the president of Transparency International Nepal.

The book features the many travails and tribulations Pandey has faced in his eventful life as a top bureaucrat who held lucrative positions such as finance secretary and finance minister, his deviations into politics, and his activities as a civil society leader. The writer frankly and candidly claims that he was a misfit almost everywhere in the Nepali context.

In the first chapter, which is titled as ‘Affluents of Kathmandu’, Pandey portrays illustrious lives of his ancestors including his own father, Khagendra Raj BA, a teacher of English, Science and Mathematics. Khagendra was picked by Commanding General Shingha Shamsher to be his private secretary. Pandey’s great grandfather and grandfather were top bureaucrats during the Rana period, and at least two of his elder brothers Dr Mrigendra Raj Pandey and Narendra Raj Pandey were renowned personalities in their respective fields. Dr Mrigendra Raj Pandey is considered one of our best brains in the field of medicine while Narendra Raj Pandey, who is no more, served the Royal Palace as top bureaucrat advising King Birendra on foreign affairs and retired as the ambassador to China. The book tends to show that despite apparent impressions of an affluent and a well-connected family, the family lost much of its financial strength and even political sheen in course of history.

The second chapter with the interrogatory title ‘Failed Civil Servant’ contains a mix of positive and negative aspects of the government administration where he served and in a short span of 19 years managed to hold the highly regarded position of a finance secretary. He acknowledges, albeit indirectly, that his connections with the then Royal Palace played a pivotal role in his quick rise up the ranks. Though he tendered his resignation citing policy differences with the government headed by Prime Minister Surya Bahadur Thapa on the eve of the national referendum held in 1980, Pandey finds Thapa as a leader imbued with all the necessary qualities and regards him as a determined, hardworking, knowledgeable and informed person.

Three other chapters are devoted to his life in the United States where he earned additional masters and PhD degrees and interacted with stalwarts from different walks of life. The sixth chapter titled ‘Kings, multiparty system and Maoists’ makes an odyssey of Nepal's quest for stability with the change of regimes, both individuals and system wise. While passing severe strictures on what he calls the political intentions of King Mahendra, Pandey liberally admires his art of decision-making, consummate skill and intelligence and regards him as someone who can get things done. But when it comes to King Birendra, Pandey portrays him as a decent person more qualified to become a constitutional monarch rather than an active king like his father.

The seventh chapter deals with Nepal’s transition from partyless Panchayat rule to the realm of republicanism. Though being quite modest in admitting his educational and professional achievements, the author highlights his determined endeavours and defining roles when it comes to political reforms in the country, from the restoration of the multiparty system to declaration of federal republic through inclusion of Maoists in the mainstream national politics.

The eighth chapter is very important as it pertains to Nepal's foreign policy with special focus on our immediate neighbours, India and China. This is all the more topical in the sense that the author used to be directly involved in most of these negotiations, especially relating to economic diplomacy and foreign aid. In this connection, he vividly depicts what he calls public lecture style approach of China's senior leader Deng Xiaoping during his talks with Prime Minister Kirtinidhi Bista during the former’s visit to Nepal in 1978. He also severely reprimands one ambassador with sarcasm branding him a suitable candidate for the post of viceroy had Nepal been a colony.

The ninth and tenth chapters deal with the writer's rather oscillating associations with various institutions and civil society including his defining linkage with Berlin-based Transparency International and several other international institutions of repute.

True to his style and approach, the author has criticised and appreciated many people he worked and was associated with, including stalwarts like Yadunath Khanal, Kul Sekhar Sharma and Bhekh Bahadur Thapa, who was instrumental in helping Pandey reach the top post of finance secretary.

With the book, Pandey gives the impression of being a rebel not happy with the scheme of things right from his early days as a civil servant to the latter part of his life.

One major lacuna of an otherwise must-read book is its sketchy conclusion. With everything covered in earlier chapters, it appears that Pandey felt he did not have anything left to conclude the book with. The book ends with words of gratitude for those who helped him and a special credit is given to his stenographer Shyam Maharjan.

————————————————————-

Ek Jyan Dui Juni

Devendra Raj Pandey

Publishers: Fineprint Books, Kathmandu, 2021

Pages: 306

Price: Rs 504

22.11°C Kathmandu

22.11°C Kathmandu