Books

Doab Dil is a pleasure to flip through and ruminate over, but it is also haphazard and pretentious

Divided into 11 chapters, the writer flits between subjects and associations with a practiced, if clumsy, tread. There is much thought spent on gardens and their benefits; changing landscapes; histories and nocturnal activities; libraries and truths.

Richa Bhattarai

“Doab Dil brings together drawings and text like two converging rivers,” claims the book’s introductory remark. It informs us, in a poetic, dreamy style, that “The fertile tract of land lying between two confluent rivers is called a doab (Persian do ab, two rivers).”

This promising preface is backed by the graphic novel’s jacket—a lone woman perched at the edge of a rock stares into the blue-white skies, cup of tea in hand, hills rolling by, fields in bloom, a river winding through. It is enough to evoke strong emotions, of an era gone by, of a memory from a distant hillock that still lingers in the mind.

Turning the page over, we spy a man who carries a house on his shoulders. On the next page, an ordinary office-goer morphs into a pot-bellied superhero. After all these whimsical creations whet our appetite, we begin to ask, so, what is this mingling of drawings and text that the writer talks of? The amalgamation is, at times, a beautiful spectacle to unravel. In other pages, while the art is spectacular, the text falters. Or is irrelevant, leaving readers flummoxed.

At the very beginning, author Sarnath Banerjee explains that this work is a product of the non-fiction texts he read over time. Eleven books are listed, ranging from a biography of Thomas Browne and a history of popular culture in the sixteenth century to Walter Benjamin and Rebecca Solnit. There is barely a thread connecting them. The author intends to bring them all together, in a mélange that could have been highly entertaining and riveting, but ends up being a pale shadow of all the books that he draws from.

Divided into 11 chapters, the writer flits between subjects and associations with a practiced, if clumsy, tread. There is much thought spent on gardens and their benefits; changing landscapes; histories and nocturnal activities; libraries and truths. The dichotomy of history and truth, a need to maintain objective balance, yet express pride in one’s identity is carefully explored.

There are also anecdotes and incidents concerning a handful of exciting personalities—Darwin and Mendel, Kitagawa Utamaro and Werner Herzog. There are men and men, an overwhelming abundance of men read, quoted and described. And as if to compensate, there are plenty of women in the illustrations, leading and working, reading and sunbathing.

There are certainly interesting nuggets that would be hard to come by otherwise. We learn of Caroline Wyburgh, arrested in London under the Contagious Diseases Act for walking unescorted: “If the arrested woman refused to undergo medical punishment, which was painful and humiliating and a punishment in itself, she would be put in prison. Strolling, wandering, roaming, straying meant different things for men and women. It had been implied that women walk not to see, but to be seen.”

We read of Søren Kierkegaard’s peculiar habit of pacing the streets. He “literally walked his way to his best ideas. The Danish philosopher often wrote his iconic essays as fast as his hand could move, which was only possible because he put all his thoughts into final form while walking. By and by, he left the streets of Copenhagen and resorted to walking in his spacious living room.”

The mention of bibliotherapy, too, is a soothing salve to book lovers—the fact that the word was “acknowledged in Dorland’s illustrated Medical Dictionary as early as 1941, and it is defined as ‘the employment of books and the reading of them in the treatment of nervous diseases.’” There are also philosophical observations, bizarre mini-stories and exaggerated emotions flung randomly into this page and that.

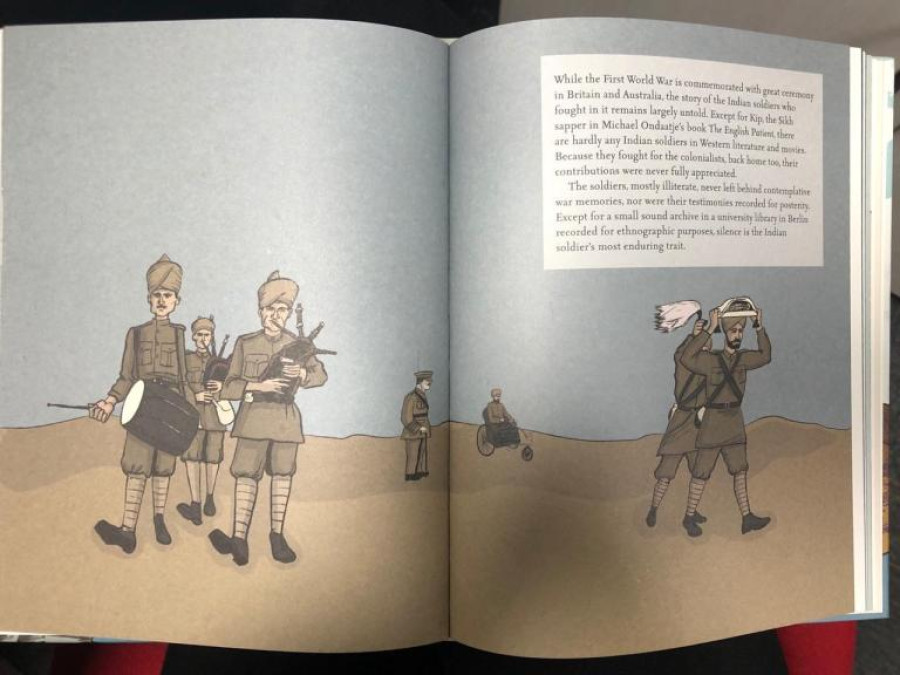

The book at times turns so haphazard and eccentric that it can leave trivia aficionados feeling dissatisfied and philosophy lovers cheated. The only true pleasure, then, comes from the pictures. It is certainly an aesthetic book, a pleasure to flip through and ruminate over. The pictures are brilliant—literally. They radiate colour and are lustrous, standing out from Banerjee’s earlier, paler illustrations. It is perhaps the colouring by Sudeep Chaudhari that leaves a warm glow on all these pages.

Dark woods remind us of Walden before we see his name on the page while Darwin and Mendel feed peas to exquisitely detailed birds as brilliant pink flowers bloom outside. Tiny leprechaun-like heads hang eerily from a lush green tree while a celebrated Japanese chef unclogs his fish-and-chips dinner from a newspaper wrapping. There is a lot of attention paid to textures and patterns, shades and pigments. There are very few of the panelled graphic comics we have come to expect, and some pages have little else except a comprehensive work of art.

One of the most interesting experiments in this graphic book is ‘The Daily Decathlon’, a series of convoluted, painful postures us humans master merely to go through work and daily life. It has a mixture of humour, irony and pathos that will stick in our minds as we prepare for one more mind-numbing day of work and mundane household chores. This chapter has no words, a format best suited to its mockery of human life.

Other chapters sometimes display a deep attachment between the text and picture, and the art is far more powerful than the words. At special moments, when you allow yourself to be lost in the author’s vision, the pages take you back to the unadulterated, priceless satisfaction of being a child, flipping through a picture book, matching story to picture.

And yet, the book suffers the fate of trying too hard, turning pretentious, haughty and ambitious when simplicity and artlessness really behooves it. It is, thankfully, never inaccessible, but it veers too close for comfort to narcissism and self-indulgence. From the very beginning, it lacks direction. There is loveliness, yes, and a far-off purpose, but it routinely languishes into oblivion. For example, the chapter on ‘Insomnia’ is a hotchpotch of third-hand experiences and surrealism.

There is a definite disjoint, an undeniable apathy and cutting off between texts on the same topic. What is truth, and what is fiction, and is the made-up paragraph necessary at all in a work such as this?

9.83°C Kathmandu

9.83°C Kathmandu