Culture & Lifestyle

Minpachas: Adventures in the time of Kathmandu’s long winters

Old residents of the Valley recall how they eagerly waited for schools to close to indulge in games or to travel to the Tarai.

Prawash Gautam

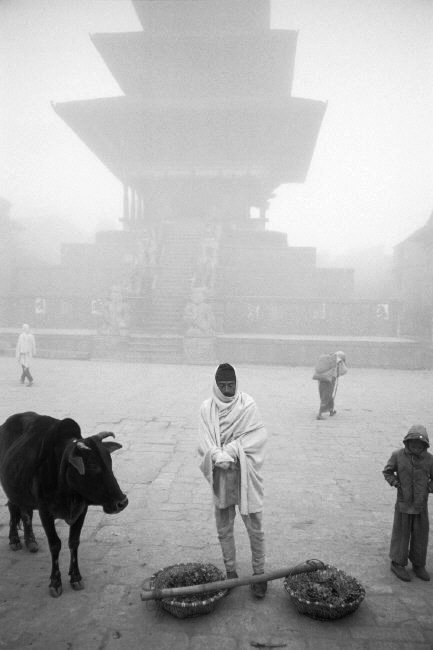

The atmosphere engulfed by a thick fog and grounds frosty, Kathmandu Valley would have already been deep into winter by mid-Mangsir. Sitting for final exams, Sagar Neupane’s hands turned stiff with freezing cold and his heart stirred a little in the fear that he might fail. But there was something that warmed his core.

“More than the fear of failing the exams, my heart would be filled with the happy anticipation of minpachas right around the corner,” said the 60-year-old from Chuchhepati.

Minpachas (min means fish, pachas is fifty in Nepali) or the fifty days from mid-Mangsir to mid-Magh were so cold that even fishes deep under the waters hid below the rocks to keep warm. And schools closed.

As biting cold gripped the valley, its students found their moment of freedom. Cut loose from the monotony of school, before them unfolded the season of games, adventures and travels.

Out of Kathmandu’s biting cold, a time of freedom

Gobinda Khanal, 87, grew up in Shankhamul by the banks of Bagmati, and carries vivid memories of Kathmandu's long, freezing winters with characteristic dense fog and frosty grounds.

“Cold would have already set in by Kartik,” he said. “Mid-Mangsir through Paush and Magh, all we saw was the dense white fog obscuring everything before us. The grounds would be white with frost. The fog cleared only around noon when the sun rays cut through it. During Paush and Magh, winter peaked.

“As children, we filled bowls with water and put them on the rooftop in the evening. In the morning, we found the water frozen into an ice sheet as thick as a table mirror. Even the flowing waters of Bagmati froze. Thin sheets of ice formed on its surface.”

To beat the cold, Kathmandu sat around its agenos, a traditional Nepali fireplace, or makal, an earthen coal-carrier.

For schools, minpachas offered a strategy to close for cold as well as wind down the academic calendar.

“For the entire year, we had to be under the watchful eyes of the teachers, but during minpachas we were free,” said Jeetendra Vaidya, 56, from Jayabageshwari.

This allowed the students time for travel, tours, games and adventure.

Travels to the Tarai farms and maternal homes

Veteran filmmaker and lyricist Yadav Kharel’s family had an estate in Saptari. Every minpachas, Kharel travelled with family to spend the holidays there. In an article "'Black out' Gariyeko Yuwaraj Birendrako Tyo Antarwarta" by Ghanendra Ojha published in Shilapatra, Kharel describes his journey to Saptari via India in the 1950s.

“After reaching Amlekhgunj on foot, we travelled via small train up to Raxaul, and from Raxaul we travelled on the train across India to reach the Indian border at Saptari. Then we crossed back to Nepal and travelled on a bullock cart to reach our farmlands,” the 81-year-old is quoted as saying.

Like Kharel, Kathmandu residents who had estates in the Tarai moved to their farmhouses during minpachas.

For Govinda Tandon, who was born and grew up in Battisputali, minpachas meant travelling to his family’s estate in Chaughada near Hetauda in Makwanpur since he was seven years old.

“We spent almost all of minpachas there and returned just a few days before the school reopened,” said the 69-year-old historian and heritage expert.

From Chaughada, Tandon also went to his maternal home in Trishuli Danda, which was not far from his family’s estate.

In fact, those growing up in the 1990s or before state that their visits to maternal homes specifically happened during these holidays.

“Whenever I think of the term minpachas, I remember my maternal home,” said 64-year-old Bishnu Bhakta Shrestha from Bhaktapur. “We travelled on foot from Kathmandu, staying over at someone’s place for the night before reaching our maternal home in Khursanitar in Nuwakot.”

Children’s season of marbles

What about the children who did not have a distant place to go to?

“Children who didn’t have anywhere far to travel made plans well in advance about how they would spend the holiday locally with friends,” said Tandon.

Among these games, one reigned across generations.

In ‘Tyas Bakhatko Nepal’, speaking about Kathmandu in the first half of the twentieth century, Bhim Bahadur Pande writes that “the most popular game for the boys was marbles”.

“The main game we played during minpachas was marbles,” said biodiversity specialist and botanist Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha, 86, speaking of his childhood in the 1940s and early 1950s in and around Mahabauddha.

Children collected packets of cigarettes—Fulmar, Busmar, Otmar, Catmar, Asha, Craven, 555—and neatly cut them into pieces and set monetary values on them. Winners of the marble games received the kittas depending on the value set for the papers.

“High-quality cigarettes like Craven and 555 had high value because they were foreign and rare, while local brands had lower value,” Shrestha said. “We stacked our wins and took home and took delight in our prize, that’s all.”

Three decades later, in the 1970s, Neupane was also playing marbles with his friends during minpachas using kittas, as was Raju Kapali from Patan in the 1980s.

When schools reopened, the marbles mysteriously disappeared, Kapali said when I interviewed him in 2018 for an article ‘Minpachas: Nepal’s Winter Holidays of Yesteryears’, published in ECS Nepal magazine. He said that children returned to school and bragged about how many marbles they had won.

Fishing in Kathmandu rivers

Rabindra Man Joshi was born in Chabahil, which, up until the 1970s, was a small settlement on the outskirts of Kathmandu. For him and his peers, minpachas meant fishing in Bagmati.

“My friends and I prepared fishing lines and caught fish in Bagmati right down Pashupati in the Tilganga area,” Joshi said in the interview for the 2018 minpachas article.

Indeed, for many boys growing up in the Valley until the 1980s, fishing was a common activity throughout the year.

“We even bunked our classes to go fishing,” Vaidya said. “Obviously, during minpachas, more leisure provided more time for fishing.”

Kathmandu’s rivers were always central to minpachas for generations before Joshi’s. When Khanal was growing up, groups of boys from Patan core came down to Shankhamul. Khanal spent many minpachas afternoons sitting by the Bagmati banks, looking at those boys fishing.

“Fresh, clear water flowed in the Bagmati and you could see a large number of asala machha [snow trouts],” Khanal said. “The boys blocked the water with sand and stones and pebbles to form a pool and caught fish using their hands.”

While fishing was a common minpachas activity for many children in different parts of Kathmandu, those growing up around airport, like Joshi and Vaidya, also had certain unique experiences. Indeed, there were games and adventures that were specific to particular localities and generations.

.jpg)

Quail fights, airport adventures

Shrestha’s father raised a few quails during the months of Mangsir-Magh every year in the 1940s and 1950s.

“He reared them for quail flights, something that specifically happened during minpachas,” said Shrestha. “During minpachas, it was common to see people gathered for cock and quail fights in different localities.”

On Tuesdays and Saturdays, the quail owners brought along their best fighters and gathered in the set locations. They placed bets of Rs10, Rs20 or sometimes even the fighting quail. Shrestha accompanied his father or went on his own, taking his most prized quail for fights.

Such fights were also organised in the Rana durbars, and Shrestha has fond memories of taking his quail for fights at Basanta Shumsher’s Bagh Durbar in Sundhara.

“We took our best quail to fight at Sushil Shumsher’s if we felt that it was good enough to win over others,” he said.

While these games, Shrestha recalled, were specific to a generation, there were adventures that were specific to particular locations and generations. Adventures in Kathmandu’s Gauchar airport stood out too.

For decades after it officially opened, the Gauchar airport was cleared of grazing cows and playing children only to allow planes to land and take off. Later, only a wire netting bound its territory. Well into the 1970s, for children from the airport’s surroundings, minpachas was a time to experience adventure like no other.

During the interview for the 2018 article, Joshi said that he and his friends often crossed over the wire nets into the airport and dug through garbage bins near the terminal building.

“We mostly looked for empty, colourful packets of cigarettes tossed by foreigners,” he said.

Sometimes, greater adventure lay in store: the hanger would be open, as well as the door of the plane inside.

“We climbed into the planes and hunted for chocolates and toffees and their bright wraps,” he said. “It was a different world inside the plane.”

Teenagers’ time for tours and picnics

By the 1970s, students were already planning and taking tours during minpachas. As a teenage student in the 1980s, Vaidya made several trips to Manakamana, Gorkha and Pokhara with his friends.

He visited Manakamana for the first time with his parents during minpachas. Later, in senior classes, he and his friends went on trips of their own.

“We waited for these trips and planned for them before minpachas started,” said Vaidya during an interview for the 2018 article. “Some groups combined trips to the historical Gorkha, then to Manakamana Temple, and then finally to Pokhara.”

Picnics were also common during minpachas. Schoolchildren formed groups and organised picnics in the open fields or jungles near their homes.

“For such picnics, we took food and other materials from our respective homes and cooked and ate in the open fields near the back of our homes. Boys and girls had separate groups, we didn’t mix,” Neupane said.

Return to books

In a letter to the editor of Gorkhapatra dated January 5, 1948, a student complained that long holidays like minpachas cut down on teaching time.

“Those who cannot afford to keep home tutors have to rely on school for their studies,” the student wrote. “Due to vacations like minpachas, Dashain and Tihar, schools run for only 4–5 months.”

The sight of their children running carefree worried some parents lest they strayed from their studies forever.

“Some of my friends played hiding from their parents,” Neupane said. “Sometimes the parents came chasing their children with sticks and took them home to study.”

Many parents and guardians found ways to continue their children’s studies. Schools in the plains would be running as were many in the hills. Many, like Kharel, who went to these places enrolled in local schools.

“I enrolled in a local school in Saptari for the entire period of minpachas,” he is quoted in the article.

Minpachas also offered a reason to celebrate books. The final exam results were out around mid-Paush. This unleashed an excitement of buying and engaging with books.

Kapil Lohani, who grew up in Kathmandu, rejoiced in receiving new books during minpachas.

“We were called to school once during Magh with our guardians to receive our results and report cards,” he writes in his article ‘Pustak Padhnuko Afnai Majja’ published in DC Nepal on March 23, 2023. “We were also handed a list of books of the upper class during the occasion.”

“We felt such unique excitement and energy while going to buy books and copies [note books] according to the list and putting covers on those books,” he said. “We spent the next few days browsing the new books.”

End of minpachas

Just like Kathmandu’s winters, minpachas is long gone.

Kathmandu’s temperature has increased in the past 30 years as climate change combines with the urban heat island (UHI) effect caused by unplanned urbanisation.

“To some extent, the end of minpachas could be due to warmer winters,” said watershed expert Madhukar Upadhya, who grew up in Deupatan. “But I think it mainly owes to the change in the academic calendar. Classes started in Falgun and we had final exams in Mangsir and then we had minpachas. When a series of changes happened in the academic calendar and curriculum with the initiation of the New Education policy in 1972, this eventually also impacted minpachas.”

More recent academic calendars start in Baisakh and end in Chaitra.

But what if Kathmandu’s winters were longer and colder and minpachas was still around?

“Where is that Bagmati where children could go fishing?” said Khanal. “Would children find fish in this Bagmati where sewage flows?” said Khanal.

But children might not even want to go out fishing in the first place, or go hunting for cigarette packets to create kittas for their marble games. Nor would mothers have to go after their children and bring them home to read. For, with the digital age, children have turned to screens as a perpetual source of entertainment.

“Today’s children don’t have the opportunity to experience the games and adventures in nature that we did,” Neupane said, echoing the sentiments of his contemporaries as well as generations before his. “Kathmandu no longer has open space for play. They too would prefer their mobile phones to outside adventures.”

9.33°C Kathmandu

9.33°C Kathmandu