Culture & Lifestyle

The fabrics of success

Heritage Fashion nurtures a family-run legacy, emphasising sustainability in the evolving landscape of the fashion industry.

Ayse Turcan

There is something comforting about the rattling of a sewing machine, especially when hearing several machines simultaneously. Paired with quiet conversations, it creates the soundscape of a garment factory. Yet, not every room in the expansive Heritage Fashion premises is filled with the familiar clatter of sewing machines. Some store fabrics or finished garments, while others house thousands of yarns and buttons. In most spaces, individuals are engrossed in the meticulous process of completing the garments, involving over 15 distinct steps.

Guiding us through the sprawling factory is Heritage Fashion’s CEO, Shashank Agrawal. He navigates the premises with ease, ascending and descending stairs, moving between buildings and transitioning through doorways from compact to spacious rooms. There’s an evident pride in showcasing this family-run enterprise.

In a well-lit hall featuring ample tables and patterns adorning the walls, a woman skillfully cuts a rich bordeaux-red fabric along a crisp white line. Shashank later reveals the finished product—a medieval-style garment crafted for a German brand with whom Heritage Fashion has maintained a steadfast 28-year partnership. Considering the industry’s fluctuating history, the enduring presence of a clothing factory over such a prolonged period is undeniably noteworthy.

Thanks to the Multi Fibre Arrangement from 1973 and its successor, the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC), the Nepali ready-made garment industry flourished over decades. The agreements regulated the amounts of clothing that developing countries could export to developed countries and defined sales quotas. This led to the manufacturing of rather low-quality products for the US market. In many cases, fabrics and patterns were delivered by the customers, and the creative work for the producing factories was limited to a minimum.

In the decade leading up to the discontinuation of the ATC, until the close of 2004, readymade garments accounted for 20 to 30 percent of the country’s total exports. However, following the end of the agreement, the industry experienced a swift decline. Just 18 months after the phase-out, a mere 30 garment factories remained. In the aftermath of this abrupt shift, the sector appeared on the verge of extinction.

Heritage Fashion is one of the few factories that survived. The company was founded in 1988 under a different name, the company initially produced on a larger scale and also exported goods to the US market. However, anticipating the phase-out of the quota system, the company strategically shifted focus to other markets like European countries and began producing higher-quality garments. This proved to be a successful strategy. “Our clients chose to stay with us when the quota phased out,” explains Shashank. A pioneer in sustainability, the company started using eco-friendly fabrics, a rarity at the time.

Another likely contributor to the company’s success is its commitment to seemingly fair working conditions. Shashank notes that the 150 employees work regular hours from nine to five, earning comparatively good wages within the industry standards. “Our tailors are among the highest paid in Nepal,” he asserts. According to him, highly skilled tailors can earn up to $350 to $400 per month. Inquiring about a man’s tenure with the company, who diligently works on a sewing machine, Shashank learns it’s been 15 years—an impressive feat in the often unpredictable garment industry.

When questioned about the reasons behind the fair treatment of workers, Shashank emphasises the importance of a mutually beneficial business scenario. “I don’t collaborate with brands pushing for cheap production,” he asserts. He underscores the need for the business to be advantageous for both the workers and the brands that engage the company.

The rest of the Nepali garment industry took a slow path to recovery after the quota phase-out. In 2019, the sector saw its exports reach a 13-year high, primarily due to a shift towards higher-quality products. However, the sector’s recovery has been slower than anticipated, according to Sanjai Agrawal, founder and chairman of Heritage Fashion, Shashank’s father, and a member of the executive committee of the Garment Association, representing the sector’s interests. Currently, the association boasts 78 member companies. Sanjai acknowledges a gradual shift towards higher quality but notes, “It’s still a minority of the companies that produce like this.” Expressing disappointment, he highlights the lack of government support for the industry post-phase-out during the pandemic and to this day.

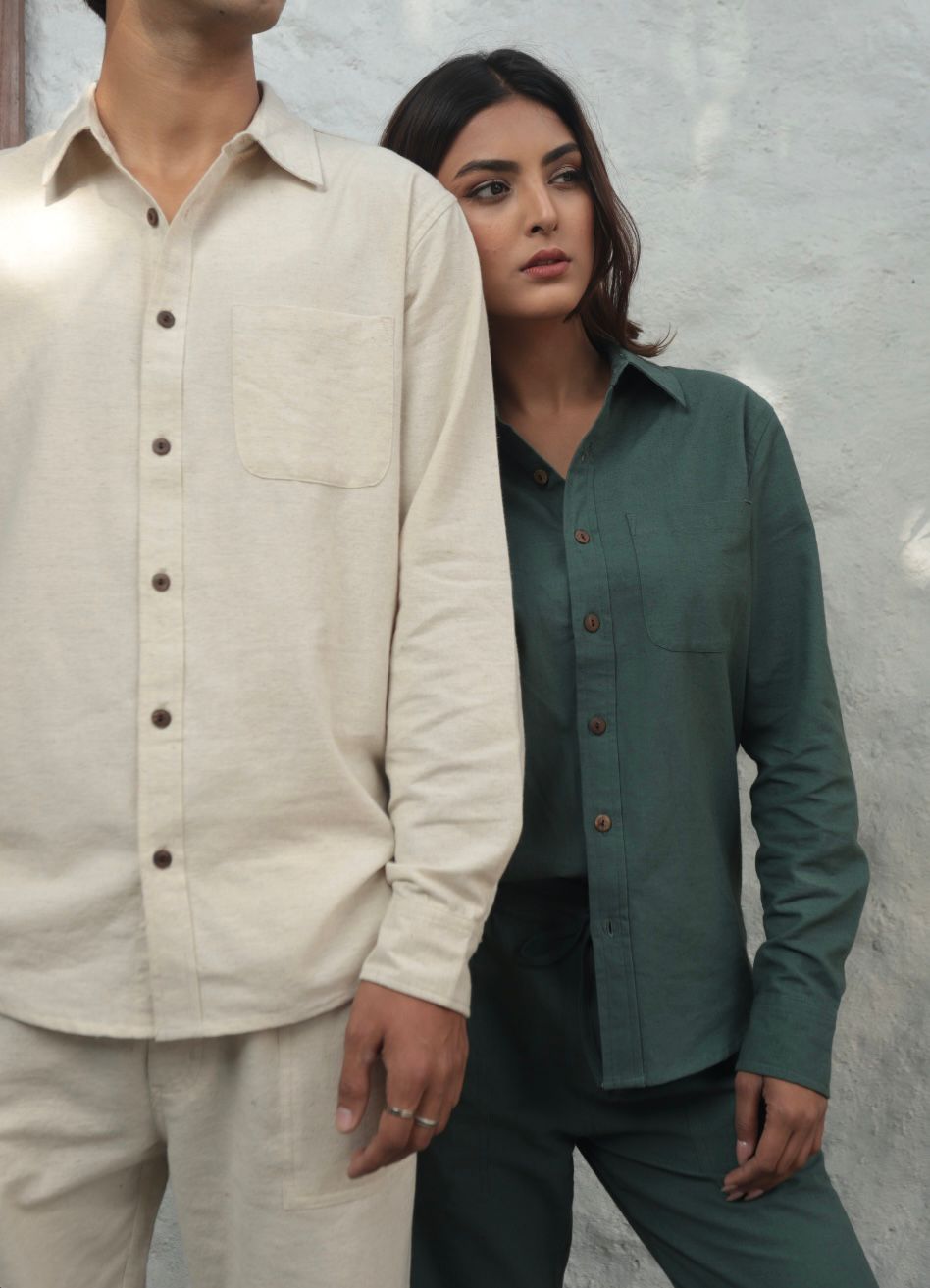

One positive outcome of the pandemic, according to Shashank, is the increased local production by Nepali brands. With Covid restrictions limiting import and export, more local firms collaborated with homegrown companies like Heritage Fashion. In addition to serving international clients, the company now works with an expanding number of Nepali brands. Basemark, self-proclaimed as the country’s “largest fashion brand”, and emerging labels like Soul Khumbu are among them.

As Shashank ascends a staircase, he introduces a smiling lady, his mother, who plays a pivotal role in the company. Describing her as the “backbone”, Shashank explains that she oversees various processes, including quality control—a critical step in the manufacturing chain. The atelier, where prototypes and samples are developed, becomes the focus. “This is from our winter 2024 collection,” Shashank points to a mannequin adorned in a stylish checked blazer with golden buttons. When he refers to “our collection”, he means the newly established family-owned brand, Arko, designed and entirely produced at Heritage Fashion.

The latest collection from the emerging brand is available for purchase online or at the recently opened Co-Creative Boutique in Thamel. Launched in September 2022, the brand focuses on sustainable everyday clothing with a unique touch, crafted in Nepal. “Between 50 and 60 percent of the fabrics we use are organic or recycled,” Shashank proudly shares, emphasising the goal to enhance sustainability each year. He showcases a fleece fabric made from recycled polyethene terephthalate (PET( bottles, which feels warm and soft to the touch.

Looking ahead, Shashank expresses no intention for significant company growth, having already slightly reduced the variety of styles produced. “I think, when you become too big, you lose your passion,” explains the factory director after about an hour as he heads to a print shop to assess potential fabric screen printing.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu