Culture & Lifestyle

Instagram was once for the artists. Today things have changed.

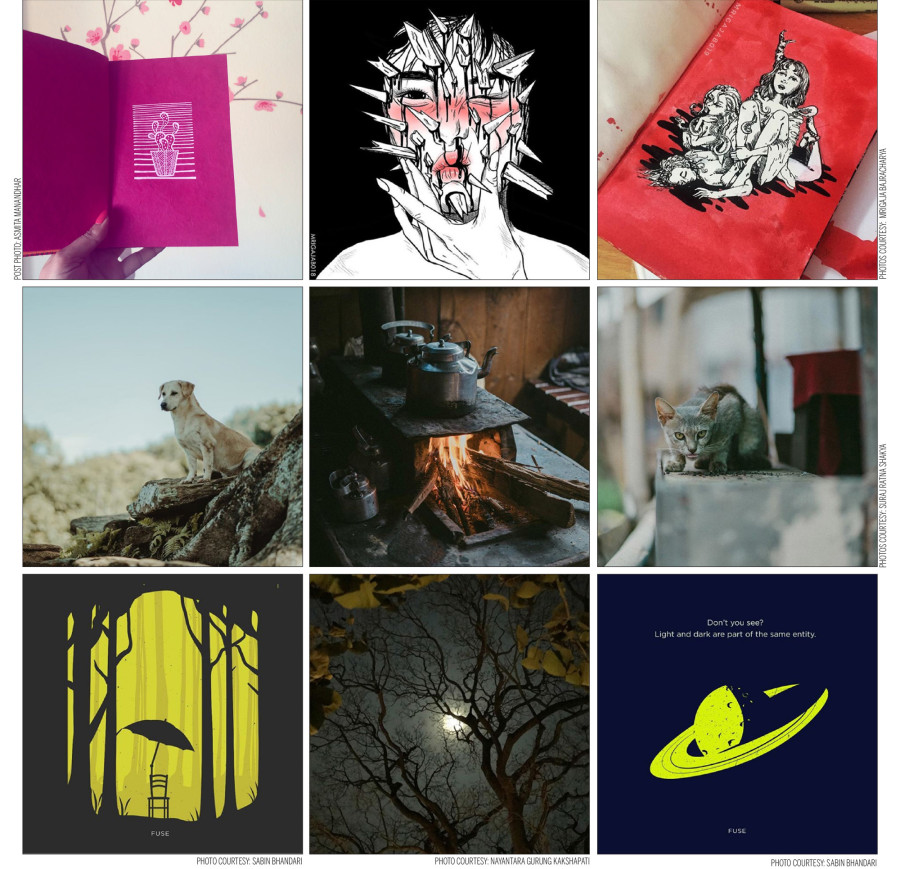

With its ever-growing userbase and commercial repurposing, is this social media platform still a place for artists?

Abani Malla

Freelance photographer Suraj Ratna Shakya first joined Instagram in 2011, sharing random and personal visual collections.

Over time Shakya started seeing his profile as a portfolio, one through which he started building his own network of connections with global artists, and, as a result, even started collaborating with other artists.

Once a vibrant community mostly occupied by photographers and enthusiasts, Instagram slowly morphed into something more. This change came after Facebook purchased the application for almost a billion dollars 18 months after its release in 2012. The purchase enabled Facebook users to inhabit the visually driven social medium in no time, and now, many communities—such as comedy, cinematography, music, travel, food, and fine arts—have delved into the application, changing what the social media platform meant for artists.

Shakya recalls using the application when having just 100 followers felt like an achievement. Instagram even featured Shakya once he reached that milestone in 2012, he says. Today, Shakya has over 14,000 followers.

“Before, I used to post whatever I wanted to,” says Shakya. “Now, I curate my feed and maintain it professionally by posting only pictures that I feel are worth exhibiting.”

Once a place simply for photos, with the co-founders’ filter feature, Instagram has now become a virtual museum of memes, illustrations, and daily snippets called stories.

“Filters are not the billion-dollar business,” said co-founder and former CEO Kevin Systrom told The New York Times in 2010. “It’s photography. The next network is people interested in sharing life visually.”

Exclusively launched for iOS users in 2010, the photo-sharing platform garnered 25,000 users within its first day of launch, becoming the “#1 free photography app”. Available for Android since 2012, it is now a global social media network with more than a billion active monthly users—there were 1,123,400 Nepali in June, according to Napoleoncat.

As well as being directly integrated with the social giant Facebook, Nepal Photo Library co-founder Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati says wider access to smartphones may have encouraged more Instagram users in Nepal.

This may have appealed to the masses but it wasn’t necessarily something artists wanted, says Shakya.

According to him, the further addition of feature accounts, which repost posts verbatim, promote artists, but they also spread redundant content. “Once Instagram turned commercial, the quantity of posts started growing rather than the quality,” he says.

Facebook’s advertising algorithms have been introduced to the once ad-free space, which changed the entire Instagram sphere by linking the sites and monetising posts. The growing commercial presence has been disturbing their reach, say creators.

“Now our posts don’t reach many users organically,” says designer Sabin Bhandari. “Like on Facebook, one has to boost posts in order to reach a wider crowd; only about 10 percent of the hard-grown followers see the posts directly through the algorithm.”

Some creators opt to use other creative applications specifically targeted to artists and photographers, such as EyeEm, 500px, Behance, Dribble, Deviantart, or VSCO, to build professional online galleries. Even after joining those sites, Instagram still remains one of the most efficient applications to showcase and discover visual artistry.

The 2016 addition of a Snapchat-style story feature has proven to be an effective means of testing artistic waters too, because they are fleeting displays of their work, rather than permanent exhibits, says Bhandari.

Those changes, however, lead to co-founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger’s exit from their own company, as a part of a larger “sour” experience under Facebook’s guidance. Although the social network’s massive growth had its own negative consequences—cyber bullying, spam, and the rise of deceiving influencers and online shops—Instagram still remains a place for good, thanks to its own limitations.

Bhandari, who joined the platform in 2015, enjoys the limitations imposed by Instagram. According to him, it enables one to carefully work on their captions and even filter their content.

However, the change in design, from the retro Instagram to a flat design oriented one, doesn’t bother users like Shakya and Bhandari. For them, the interface changes were user-friendly enough to continue relatively undisturbed.

Amidst all the changes, Instagram has preserved its distinct original feature: its feed. The gallery still lets one curate their own profile carefully, according to their own taste, which Instagram users call “feed game”.

“One can decipher the personality and image of a user through their feed,” says Nepal Photo Library’s Kakshapati. “I follow people based on the work they exhibit.”

As more profiles join the community, it has slowly started to become like Facebook, which Bhandari describes as “noisy and crowded.”

The challenge for users is to find communities they’re interested in, within a pool of irrelevant content that repels them from using the application. “As the application was focused on photography, I wasn’t much interested initially,” says Bhandari. “But once I discovered good artists, the community started to inspire and encourage me to be creatively active.” Bhandari believes core features that let users follow, unfollow, and block profiles solve the problem.

With some hurdles here and there, Instagram still remains to let the community of artists thrive within its vast outskirts. For Nepali artists, the platform’s growth has given great opportunities to connect with global and local communities, but it depends upon how they limit their distraction. Thankfully, however, the application still lets them control their interactions.

“If one curates their feed well, the creative community will thrive,” says photographer Shakya. “Otherwise, you’re just going to make noise.”

9.83°C Kathmandu

9.83°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)