Politics

Could the ordinances backfire on coalition if Assembly rejects one?

Constitutional experts argue that losing a majority in the upper house is no threat to the government.

Binod Ghimire

The ruling alliance is in a spot of bother after the Janata Samajbadi Party-Nepal (JSP-Nepal), on Tuesday, decided to vote against the ordinance to amend land related laws.

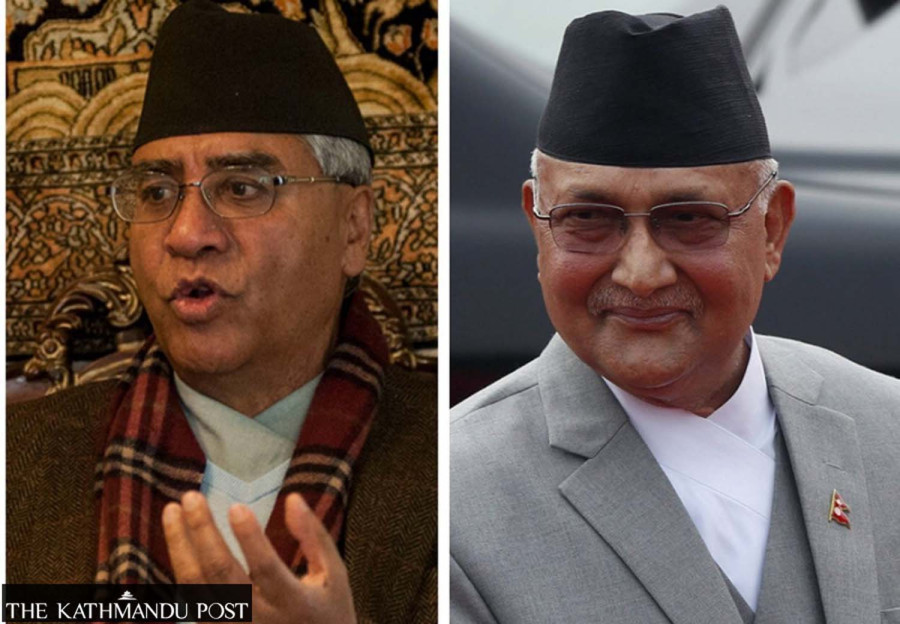

Its trouble escalated after the Loktantrik Samajbadi Party, which is a partner in the KP Sharma Oli government, decided on similar lines. Both the Madhes-based parties have claimed that the ordinance only benefits the corrupt, land mafia and people close to the government who eye public land across the country.

Though the UML-Congress coalition enjoys a thumping majority in the House of Representatives, it is shy of the halfway mark in the National Assembly, the upper house. As a result, the Oli administration has not tabled six different ordinances in Parliament for endorsement even though they were scheduled to be put to a vote last week.

Now opposition parties claim a government that doesn’t have strength to get the ordinances and bills through Parliament has no authority to remain in power. Speaking at a public function on Wednesday, Jhala Nath Khanal, former prime minister and senior CPN (Unified Socialist) leader, claimed the CPN-UML and the Nepali Congress have no right to remain in government.

“The government is shying away from tabling the ordinances in Parliament because there is no hope of their endorsement. The government does not have a majority in both Houses. Can the two parties still remain in the government?” he questioned.

The Congress has 16 seats in the 59-strong upper house and the UML has 10 seats. If Anjan Shakya and Bamdev Gautam, both nominated by the government, side with the ruling alliance, it will have 28 seats, two short of a majority.

Unlike the claim of the opposition parties, constitutional experts think that losing a majority in the upper house is no threat to the government. It is the lower house with the sole authority to make and unmake governments. As long as it commands a majority in the House of Representatives, the Oli government is comfortable irrespective of whether the ordinances or bills get through the National Assembly, they say.

“There can be no moral or legal question before the government even if it fails to prove a majority in the National Assembly,” said senior advocate Bipin Adhikari, professor at the Kathmandu University School of Law. “However, it means the government is not strong enough to make the policy revisions it wants.”

Ever since its formation in July, the Congress and the UML have been boasting that the incumbent government is strong and even has the mandate to revisit the Constitution of Nepal. But its recent struggle to get the parliamentary nod on ordinances suggests the claims were built on a shallow foundation.

“Failure to command a majority in the upper house entails that the ruling coalition brings other parties on board,” said Adhikari.

Ruling party leaders say they are in continuous dialogue with different parties including the JSP-Nepal. Shyam Ghimire, the Congress chief whip, said the ruling party is surprised at the LSP’s decision, saying a party in the government cannot stand against any bill or ordinance. The Oli-led Cabinet, which had participation of Sharat Singh Bhandari, a JSP leader, as minister, had recommended the President issue the ordinances.

“The ruling coalition is confident that the ordinances will be endorsed,” said Ghimire. “We are in serious talks with the JSP and other parties.”

The ruling parties want the Upendra Yadav-led JSP-Nepal, with three seats in the upper house, to vote for the ordinances. If not, they want both Madhes-based parties to abstain from the voting process.

Any bills including the ordinances can be endorsed by a majority of the total present members in the particular meeting. Absence of four lawmakers would mean the ruling side would have 28 votes against 27 of the opposition parties including the chair who can only cast decisive votes.

If the ruling parties’ attempts to secure a majority for the ordinances fail, it has no option but to drop them from parliamentary agenda. They become ineffective if they don’t get through both Houses within 60 days.

16.41°C Kathmandu

16.41°C Kathmandu