Opinion

The provincial budgets are far from being implementable

They are a mere copy of the federal budget with unrealistic goals.

Chandan Sapkota

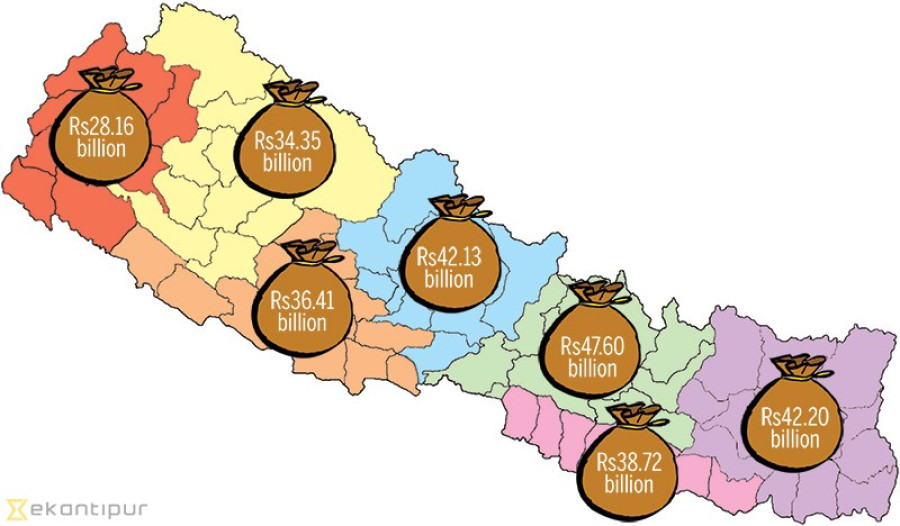

Earlier this week, the finance ministers of the seven provinces presented their budgets for the fiscal year 2019-20 to their respective provincial assemblies. This is the second full budget the provinces have unveiled. They have relied on federal fiscal transfers (in the form of fiscal equalisation, conditional, matching and special grants), value-added tax and internal excise duty collections shared by the federal government, and cash savings from the fiscal year 2018-19 (which basically is the unspent resources from last fiscal year) to finance a combined Rs259.6 billion expenditure plan in the seven provinces.

The internal revenue mobilisation target is too small compared to the expenditure needs, as the provinces are still struggling with adequate human resources and a systematic mechanism to collect taxes that fall under their jurisdiction. Still, the provinces have increased the budget envelope drastically by including too many projects that they will not be able to execute. Furthermore, they have copied wholesale some of the bad budget practices of the federal government, including funds for parliamentarians.

Provincial outlays

Province 1 has earmarked Rs42.4 billion for FY2019-20—of which about 55.6 percent is capital expenditure. It is planning to meet 75 percent of the expenditure need by relying on fiscal transfers and revenue shared by the federal government, 15.7 percent using last year’s savings, and the rest by mobilising internal revenue and borrowing about Rs10 million from the internal market. Similarly, Province 2 has earmarked Rs37.4 billion for FY2019-20—of which about half is capital expenditure. It is planning to meet 69 percent of the expenditure need by relying on fiscal transfers and revenue shared by the federal government, 19.9 percent using last year’s savings, and the rest by mobilising internal revenue and borrowing about Rs1.3 billion from the internal market.

Province 3 has earmarked Rs47.6 billion—of which about 48 percent is capital expenditure. It is planning to meet 66.1 percent of the expenditure need by relying on fiscal transfers and revenue shared by the federal government, 14.2 percent using last year’s savings, and the rest by mobilising internal revenue. Meanwhile, Gandaki has earmarked Rs32.1 billion—of which about 61.8 percent is capital expenditure. It is planning to meet 68.7 percent of the expenditure need by relying on fiscal transfers and revenue shared by the federal government, 14.9 percent using last year’s savings (unspent budget), and the rest by mobilising internal revenue and borrowing about Rs2 billion from the internal market and federal government.

Province 5 has earmarked Rs36.4 billion for FY2019-20—of which about 51 percent is capital expenditure. It is planning to meet 73.7 percent of the expenditure need by relying on fiscal transfers and revenue shared by the federal government, 13.7 percent using last year’s savings (unspent budget), and the rest by mobilising internal revenue. Similarly, Karnali has earmarked Rs34.4 billion—of which about 62 percent is capital expenditure. It is planning to meet 71 percent of the expenditure need by relying on fiscal transfers and revenue shared by the federal government, 26 percent using last year’s savings (unspent budget), and the rest by mobilising internal revenue and borrowing about Rs800 million from the internal market.

Meanwhile, Sudurpaschim has earmarked Rs28.2 billion for the upcoming fiscal year—of which about 62 percent is capital expenditure. It is planning to meet 81.6 percent of the expenditure need by relying on fiscal transfers and revenue shared by the federal government, 17 percent using last year’s savings (unspent budget), and the rest by mobilising internal revenue.

Defining features

First, compared to the first provincial budget, this one is much more coherent in terms of presentation and accounting methodology. This sort of coherency in budget preparation across the three tiers of government is essential for budget accounting as well as for informed analysis. However, there is no need to make provincial budget-making processes and practices an exact copy of the federal budget, especially the tendency to distribute meagre resources across sectors and in projects that are not implementation-ready. This has heightened the risk of malpractices and budget under-execution. The provincial government should ideally focus on priorities that are unique to the provinces, create an institutional mechanism to link and cooperate on projects and programmes with local governments and the federal government, and compete with each other to attract private sector investment by offering the best investment regime. This is the whole essence of cooperative and competitive federalism. Unfortunately, this characteristic is missing in the provincial budgets.

Second, provincial finance ministers have copied the federal government’s unpopular programme to distribute money to parliamentarians to fund projects of their choosing. This is wasteful spending riddled with malpractices and corruption. Except in the case of provinces 5 and Gandaki, the money allocated to fund pet projects of assembly members account for more than 20 percent of their internal revenue. For instance, such spending account for almost half of the projected internal revenue of Province 1. It is 78.4 percent of projected internal revenue in the case of Province 2, 21.1 percent in Province 3, 342.4 percent in Karnali province, and 282.3 percent in Sudur Paschim Province. Cumulatively, federal and provincial constituency development funds amount to about 0.7 percent of the GDP. Gradually, even the 753 local governments will follow the same practice when they present their budgets.

Third, Provinces 3, Gandaki and Karnali are planning to borrow money to meet expenditure needs. Although the federal government has published guidelines for internal borrowing by provincial and local governments, they haven’t actively borrowed money from the internal market so far. It remains to be seen how they will price their bills and bonds, and what interest rates will be charged by the market.

Fourth, as in the case with the federal budget, none of the provincial finance ministers has presented a viable plan for effective budget implementation. They have hardly used half of the allocated budget for this fiscal year and they still lack the required institutional setup and human resources to plan and implement projects. The tussle between federal and provincial governments over staff recruitment is not over yet. Capital spending will be affected by the lack of coordination between federal and provincial governments (especially on timely delegation of projects and authority to use funds), lack of human resources and institutional setup, and lack required provincial laws and regulations.

Sapkota is an economist.

8.67°C Kathmandu

8.67°C Kathmandu