Opinion

A lot to do

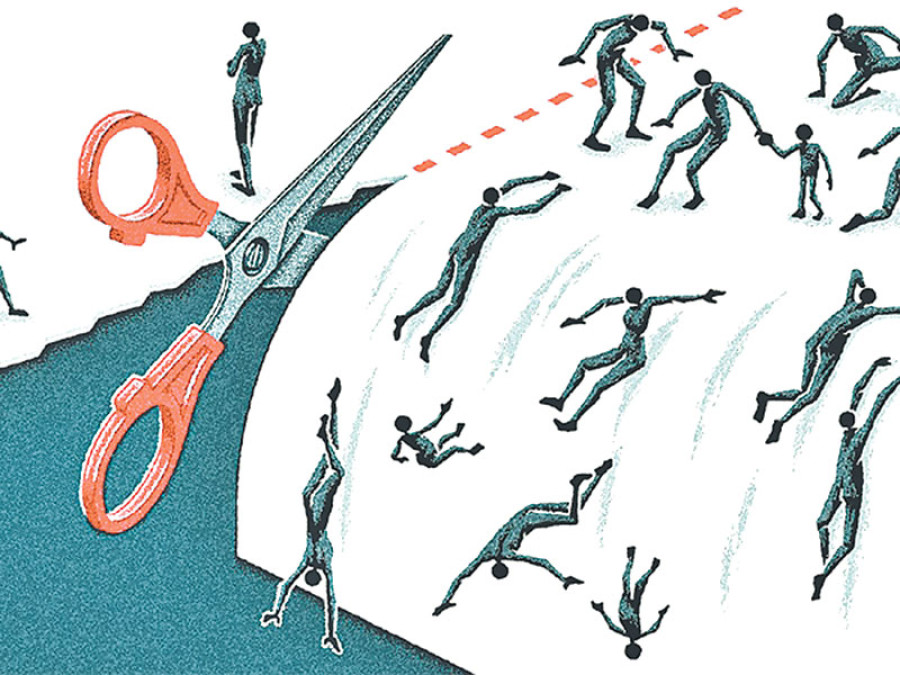

Decentralisation was expected to solve the problem of governance but there is a long way to go

Upendra Bahadur BK

Deepening democracy at the local level leads to the empowerment of citizens. Empowerment is a process of enhancing the capabilities of diverse groups to hold and influence the stakeholders accountable to them. Local level abounds in resources and capabilities including the social, cultural, economic and political processes for mutual interactions and interdependences among the social groups. Local governance is beyond the constraints of centralisation and recentralisation of powers and authorities.

Meaningful participation of citizens in decision-making processes heralds a social justice irrespective of their diversities and differences. Once upon a time, highlighting the significance of grassroots, Chanakya had rightly said, “Power comes from the countryside”.

As seen in Surkhet

The successful completion of elections at all three tiers—the federal, provincial and local level, ended a long political impasse, especially at the local level. Citizens contribute to the renewal of a political system through voting on the one hand and on the other hand make a contribution by paying taxes to the government. Local levels are therefore constitutionally endowed with legislative, executive and judicial powers to effectively ease the problems faced by marginalised and deprived people and provide access to social development to all.

The local democratic practices at eight local level units in Surkhet district is a case in point.

As we enter the fiscal year 2018/2019, the local governments have completed their first year. Citizens have a direct access to the representatives and bureaucracy to settle the grievances in the course of service delivery. The incorporation of plans and programs suggests that there is a system of organising assemblies and meetings of citizens from different walks of life at the settlement level to identify and assess the local needs. The list of demands underlined by the community people should be submitted to the ward level for a decision. The priority of needs made by the ward should then be forwarded either to the village council

or to the municipal council for policy alternatives.

Despite the guidance, the predominance of local elites and tycoons subdues the voices of poor and marginalised sections in formal meetings at the micro-level. The citizens who attend the initial stage of such planning meeting are barely able to muster the courage to voice their concerns.

Demands pertaining to areas to work upon, that is ultimately sent to the ward, too is narrowly prepared by a few people who are known to be close to the leaders. The ward chairperson and his/her political allies intend to maneuver the demands aligning with the political influence. As a result, both the village and municipal councils seem to be filled with hubris when it came to manipulating the demands stemming from the bottom.

Regrettably, even the local level governance did not seem immune to the (in)famous Asharey Bikas—the tendency of hurriedly wasting resources at the end of Ashar. The local development schemes of irrigation, roads and schools are carried out through a way of formulation of users’ committees rather than a process of tendering. The members of users’ committees are nominated by the chairpersons and their aides instead of selection through a meeting of users. Besides, members are sought from own family. Such practices pave way to hide and embezzle resources for their personal gains.

The institutionalisation of planned developmental practices is the need of the hour to orient and reduce poverty and underdevelopment handed down for generations. The politics of appeasement for party workers and coterie by involving them in small sized development activities is another problem. It results in systematic corruption and further worsens the the plight of local people.

Pay heed

The above-mentioned instances are just the tip of the iceberg. The stakeholders do not attempt to learn from their past mistakes as they are used to taking benefits of local resources. The example of drinking water is enough to illustrate a worst case scenario.

People are still deprived of the access to drinking water when annually budget is allotted for projects pertaining to drinking water. The intra party and inter party conflicts do not represent a scenario of expected changes to strengthen democracy but only revolve around the concerns how to take benefits of public resources. Differences vanish among the stakeholders while enjoying benefits and they reemerge according to their convenience.

The slogan of good governance serves as the external tooth of an elephant that is only used to demonstrate but has very little actual usage. A survey was conducted among one hundred fifty stakeholders of different identities covering all levels. 70 percent of the respondents opined that the volume of corruption has been increased compared to the past due to unholy alliance between bureaucrats and the politicians.

More than 60 percent of the respondents mentioned that the targeting of resources is determined by the elite whims that ultimately pushes the common voices to the periphery. The decisions to open a gymnasium and purchase a drone camera in the rural areas are testament to their mindless spending.

A further sixty-five percent of the respondents said that local networks and pressure groups formed seem to have been indulging in collaborating with local elites to take benefits of public resources rather than voicing about changes.

Local democracy is a way of attaining autonomy for citizens to change unchanged power relations in the society. Only the empowered citizens can change the landscape of domination in governance process. We lack a vibrant civil society to think of the social issues benignly.

Local governments have the ability to inspire and lead communities through meaningful engagement. The people have huge expectations from them. They should do their best not to disappoint the citizenry.

B.K. is a lecturer of Political Science at the Department of International Relations and Diplomacy at Mid-Western University, Surkhet, Nepal

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu