Opinion

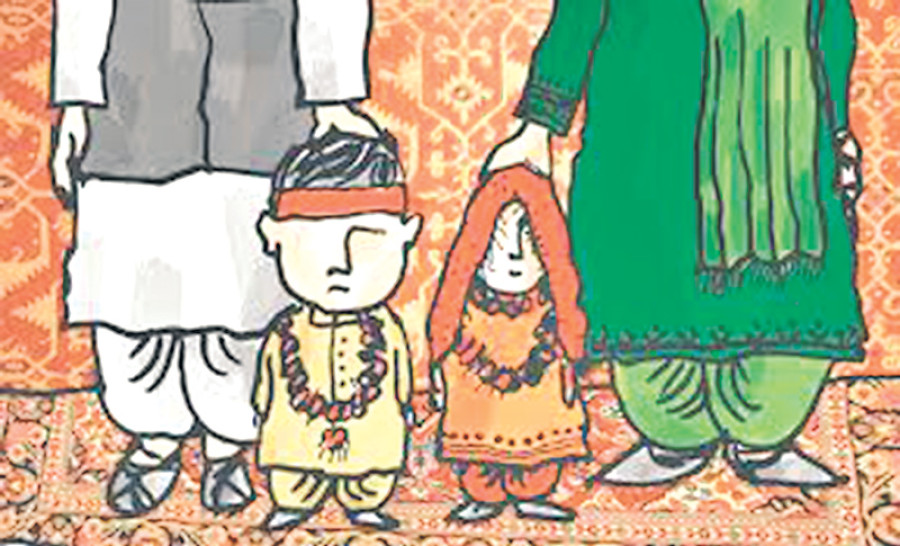

A national shame

Even as Nepal preps to plunge into the modern age, evils like child marriage persist

Maina Dhital

While Nepal’s leaders are focusing on big infrastructure projects like railways and metros, news stories about child marriage frequently appear in the media which shows that the social mind set is still basically backward. The minimum marriageable age for girls is 20 years, but more than one-third of Nepali girls get married before that age. According to the Girls Not Brides, Nepal ranks in the 16th position in the global child marriage index. In South Asia, Nepal has the second highest rate of child marriage of 37 percent after Bangladesh (59 percent).

Child marriage has become a big challenge in South Asia. Studies indicate that many factors including poverty, rape, dowry, physical security, deep-rooted social norms and values including family honour, culture and religion contribute to child marriage. In many cases, parents force children to marry at an early age. There are also examples of young girls and boys eloping when families and society do not accept their relationship.

As per the reports

In 2016, Human Rights Watch recorded a case in which a 14-year-old girl identified as Sharmila ‘eloped at age 12 and married an 18-year-old man’. According to her, when talk spread in the village about her relationship with her boyfriend, her parents tried to separate them and that forced them to elope. As physical relations before marriage is forbidden in most South Asian societies, parents are afraid of their daughters getting a boyfriend and having sexual relations before marriage.

Furthermore, a girl marrying a younger boy is generally not considered as a good thing given the patriarchal values of society. This mentality has reinforced the practice of child marriage, especially of girls. Many parents still believe that if they do not marry off their daughter when she is young, it will be difficult to find the ‘right husband’ for her, and she may end up an old maid. For many poor parents, early marriage has become a means of transferring the responsibility of their daughter’s care to another family. Furthermore, poor parents, especially in Tarai-Madhes, believe that early marriage can reduce the burden of dowry as the amount is strongly associated with the groom’s education, earning and family status.

A report entitled Economic Impacts of Child Marriage issued by the World Bank and the International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW) indicates that the major economic impacts of child marriage are related to education, income, fertility and population growth, and the health of kids born to young mums. Child marriage has significant ramifications on women’s potential earnings and productivity. In many cases, married girls are forced to quit school to carry out household responsibilities. It also downgrades their prospects of entering the labour market. Those who work for the household to survive will have to work for low pay due to lack of higher education and skills. It further leads to the vicious circle of poverty. Additionally, it restrains their influence within the family and curbs their bargaining power.

The girls who are forced to get married at an early age often face the risk of early pregnancy and childbirth leading to death. According to Unicef, ‘girls between the ages of 15 and 19 are twice as likely to die of pregnancy and childbirth complications as women between ages of 20 and 24’. They are also vulnerable to life-threatening diseases like HIV and AIDS. Despite the multiple disadvantages of child marriage, the consequences are hugely understated in Nepali society.

The World Bank and ICRW report suggests that ‘the investments in ending child marriage can help countries achieve multiple development goals’. They can increase their national earning by 1 percent on average by stopping child marriage which can save the global economy trillions of dollars by 2030. Nepal alone can save $710.6 million annually by ending child marriage, according to the study. In order to eliminate child marriage, the federal, provincial and local governments should collaborate and speed up multiple initiatives. Similarly, social awareness about child marriage can be raised by educating and mobilising local religious, social and political leaders including teachers.

Role of local government

Rural municipalities and their ward units should be held responsible if child marriages occur within their jurisdictions because they are the ones who maintain marriage records. These offices should not be allowed to issue marriage certificates to underage couples. There should be a provision to void child marriages across the country. The government can also introduce incentive programmes to support families. For instance, providing compulsory and free education up to the undergraduate level and economic opportunities to unmarried girls may be helpful in controlling child marriage.

Local governments and NGOs can encourage families or girls by publicly recognising those who get married only after graduation. Also, law enforcement authorities and local governments need to collaborate with the local media to raise awareness against child marriage. Without strong government intervention, NGO efforts alone cannot bring the desired outcome in this regard. An effective mechanism is also required to receive complaints against child marriage and take immediate action.

As dowry has encouraged child marriage, especially among poor families, in the Tarai region, local and provincial governments should effectively enforce the law against the practice. Families should also be held accountable for underage marriages. To end impunity, laws should be effectively enforced and regulated. As the country has already come out of political transition, there should not

be any excuse for lack of law enforcement. Getting rid of child marriage should be as important as building infrastructure for the government. Regardless of whatever development is achieved, it will not make the people proud as long as child marriage persists as a national shame.

Dhital is a US-based freelance journalist

13.85°C Kathmandu

13.85°C Kathmandu