Opinion

Locomotive dreams

In the past, Nepal shunned the idea of developing a railway network and focused on roads instead

Amish Raj Mulmi

After being told for many years that railways were not feasible in Nepal because of the terrain and the high capital costs, we are faced with a future where China and India are both connected to Kathmandu via trains. Prime Minister KP Oli’s Delhi visit, successful by all accounts, saw agreements being signed on initiating a railway link between Kathmandu and Raxaul, and on utilising the waterways for transport. India is stepping into an infrastructural game where China has already taken the lead. But given the delay in any infrastructure project in Nepal, it’d be prudent to hold any expectations until the locomotive starts rolling.

Having said that, Nepal’s history with railways goes back before the 1920s, when the Amlekhganj-Raxaul railway was initiated. Much of it revolved around the export of products, especially timber, to India during British times, rather than increasing connectivity within the country. While under the Ranas there was an obvious hesitation to improve transportation systems inside Nepal unless it was for economic reasons, post 1950, despite a World Bank transport master plan that outlined railway development in Nepal, the development of road networks took priority.

In many ways, the expansion of railways into northern India ‘pushed the country deeper into the vortex of India’s growing economy’, as historian MC Regmi put it: ‘The commercial importance of existing towns on the Nepal-India border, particularly Nepalgunj, increased almost overnight. In the central sector, the Nepali border market town athwart the Indian railroad terminus at Raxaul was rebuilt and renamed as Birgunj, obviously after Prime Minister Bir Shumsher.’

The beginnings

When the first Indian passenger train chugged from Bombay to Thane in April 1853, it would end up being a ‘memorable day’ not just for the British, but for the Ranas in Nepal too. As the British developed an infrastructural network across much of northern India, the demand for timber—to be used as railway sleepers, railroad ties, planks for bridges, or for use in homes—grew exponentially. As most of north India’s sal forests began to be depleted, “the major sources of supply were, consequently, left on the Nepali side of the Tarai border.” An 1897 report stated, “The great marts of Nepal on the border of Oudh are Golamandi and Banki, alias Nepalgunj… The policy of the Nepal Durbar is to force all hill produce to be brought to these places,” from whereon Nepali timber was sent forth to India.

Regmi notes that the waterways earlier used for trade with India declined in importance after the introduction of railway junctions near the Indo-Nepal border, as railways were safer, more reliable and even ‘small consignments’ could be transported on them. Although railway lines on the Indian side of Nepalgunj opened in 1885, and another line connected Forbesganj in eastern Bihar, adjoining Rangeli, in 1890, by 1908, ‘the bulk of the [Indo-Nepal] trade pass[ed] through Raxaul, the terminus of the Sugauli-Raxaul branch railway’, which was connected by rail in 1898. ‘Thanks to those railroad connections, it now became possible to transport Nepal’s exports by boat or ox-cart up to the nearest Indian railroad terminus and then by railroad to different destinations in India,’ wrote Regmi in An Economic History of Nepal (1846-1901).

The extraction of timber also provided the impetus for Chandra Shamsher to rope in JV Collier, a British forestry official, in 1923, who had a ‘short stretch of narrow gauge’ pushed into the west Tarai. Hunter-conservationist Jim Corbett writes of the timber tramway: ‘The [Mahakali/Sharda river] gorge is four miles long and was at one time traversed by a tramway line blasted out of the rock cliff…[it] has long since been swept away by landslides and floods.’ The first passenger railway inside Nepal, between Amlekhganj and Raxaul began in 1927, while the now defunct Janakpur-Jaynagar line began in 1937.

Although intended for timber export, with multiple railheads now across the border, and because of the lack of roads within Nepal, transportation began to witness a distinct change with the railways. Historian Perceval Landon wrote in 1928, ‘For any long distance, it is now easier and quicker and, it may be added, cheaper for a Nepalese to make his way either to one of the railway stations on the Indian border....and then join the Indian railway system for an excursion east or west even when his destination is in his own country.’

This was a massive disruption to existing transportation networks within Nepal, even the few that existed. New economies started to emerge around the border towns near railheads. One visible impact of railroads was on the trans-Himalayan trade, where Newar traders found it simpler to take the train to Calcutta, from where they would purchase their wares, and then onwards to Lhasa via Kalimpong than using the old passes of Kuti and Kerung. Nepal’s external trade began to be shaped by its proximity to railway connections in India, which continued into the modern era.

The recent past

‘The principal function of railways in Nepal will be to facilitate and improve the movement of goods into and out of Nepal across the Indian Border. This will be done by, in effect, extending the most important Indian Railways into Nepal,’ concluded a 1965 World Bank report on a national transport system for Nepal.

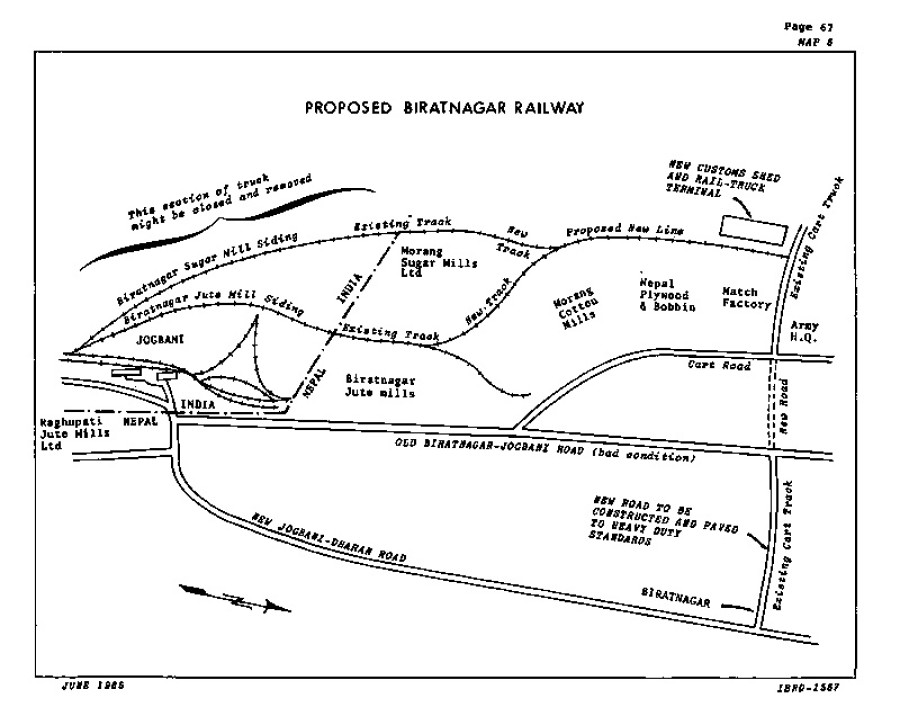

The report recommended Nepal develop three cross-border railway terminals in Nepalganj, Biratnagar and Birgunj. ‘The general idea is for the Indian Railways to provide all freight cars, use their own locomotives, and maintain all rolling equipment necessary for the operation of these terminal railways. The Indian Railways would bill each local Nepal railway separately for the actual cost of services provided.’ The masterplan suggested the construction of a new Birgunj railway terminal beyond the 1927 Nepal Government Railway between Amlekhganj and Raxaul, as ‘the present [...] narrowgauge line cannot perform the necessary terminal function because of the change of gauge at Raxaul.’ In Biratnagar, the new terminal would include petroleum storage tanks (see picture), while at Nepalganj, a feasibility study was recommended first. The study presciently said the line between Amlekhganj and Raxaul should not continue because of high repair costs, and the ‘serious problem’ of changing gauges at Raxaul. The line was finally shut down in 1965 itself. The ‘continued operation’ of the Janakpur-Jayanagar line was recommended after repairs, but even then, ‘the railway’s value beyond [five to ten years] is questionable’.

This report highlighted the low volumes of passenger movement which would negate the investment costs required to develop railways within the country. The construction of an East-West railways in the Tarai was ‘technically feasible, though costly’, as were any ‘North-South’ lines connecting the plains to the hills. ‘The construction of an east-west railway out of Kathmandu was considered completely impractical because of extremely high costs and low traffic potentials suitable to a railway. Further, such a line would operate under a severe economic handicap if it could not be linked at some point to an existing railway system.’

Times change

But the report’s railway recommendations didn’t go through. Post 1950, up to 40 percent of the total outlay for the first five-year plan, declining to 35 percent in the third five-year plan, was dedicated to upgrading transport infrastructure in Nepal. However, the development of railways was not as much a priority as roads were, as former Nepal Rastra Bank governor Yadav Prasad Pant wrote in 1962: ‘In view of the country’s limited resources in the years to come, it would be necessary to concentrate on one mode of transport. For topographical reasons, development of roads will be most suitable for Nepal.’ It’d suffice to say this remained the policy directive until most recently.

Now, with a future where Kathmandu could see trains both to China and India, a reasonable assumption holds that a China-Nepal-India railway connection that turns Nepal into a transit market will be of greater advantage than discrete and unconnected networks with the two neighbours. The future development of railways in Nepal, although geopolitically motivated, is dependent on its long-term economic viability. China and India may provide the technical know-how and the capital required, but it’ll be up to us to gauge what we want to do with it.

19.05°C Kathmandu

19.05°C Kathmandu