Opinion

Down and out

Government schools need to improve; making education free is not the solution—at least for now

Shail Suman Silwal

Imagine a new Nepal—one with free education—where the rich and the poor could assemble in the same hall, play in the same school ground and study in the same class. Sounds alluring, right? But can Nepal afford free education? Is free education actually free? With some political parties seriously pitching the idea of free education, we should analyse how feasible it is in today’s context.

There is indeed a big difference between the performance of students from private and public schools. Government schools are in decline; the teaching quality is below par and there are not enough resources. Students do not receive adequate practical knowledge and English skills. Too often, classes are not held regularly. This makes it tough for government school students to compete in the global arena. Political influence and political instability add to this problem.

Students who perform poorly are usually from public schools whose success rate in SLC exams is low. This is all the more disheartening, given that a big majority of Nepali student go to public schools.

Dissatisfied with the public schools’ inability to prepare their children for a cut-throat competitive world, parents who can afford it either send their children to private schools or abroad. Private schools hold classes regularly. They follow a strict calendar and timetable. Assessments and staff meetings are held regularly to evaluate and discuss students’ performance.

Refuge for the disadvantaged

In public schools, teacher absenteeism and turnover are high. Weak management skills, inconsistent appraisals, appointments and promotions through political affiliations or kinship ties have often left teachers suffering from low morale. There is hardly any extra support for struggling students. There is little focus on critical thinking, fostering understanding and applying ideas to practice.

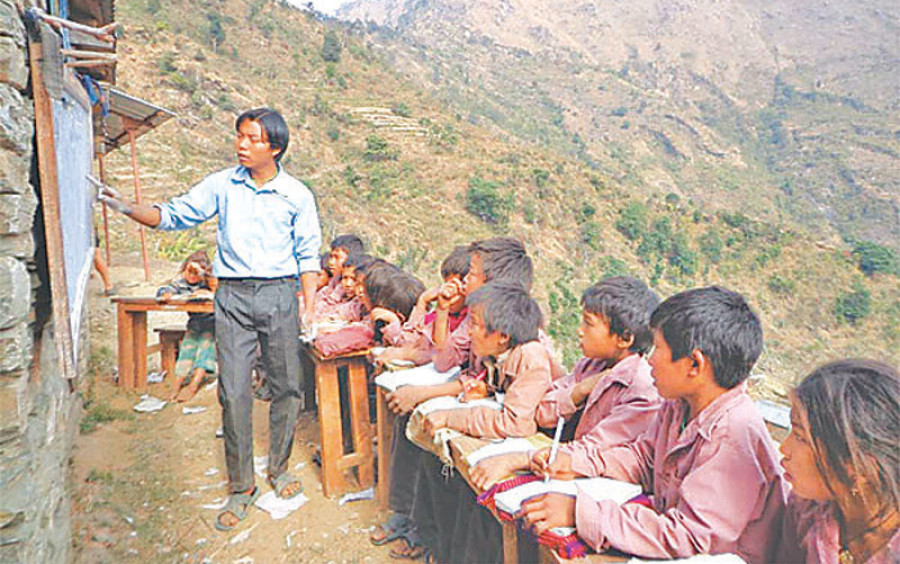

Libraries may have been set up, but the environment for students to go there and study is lacking. Often, schools in rural areas are dirty and without inadequate infrastructure. Many of them lack proper toilet facilities, due to which female students have difficulty going to school when they are menstruating. Even when the resources are available, they are not utilised to their full potential. There are areas where the government is unable to send textbooks, sometimes even until the entire course is completed. In public colleges, political interference by student and teacher unions has hit education hard. When the demands of the student leaders are not met, they are likely to resort to vandalism and agitation.

Public schools have now become a refuge for the children of the poor and the disadvantaged families. The growing gap between the two types of schools is widening social stratification and undermining our social cohesion.

Undiscovered talent

In such a bleak scenario, will free education offer a solution? Will the culture of mediocrity disappear if education is made free? What will happen to the investment that has been made in the private sector? Even if the country starts providing free education, it cannot be assured that students would take school more seriously. Most people value something only when they have to pay for it. “Parents have little or no investment in their children’s education”, states Nawang Thora Sherpa, a ‘Teach for Nepal’ fellow. “I conducted a diagnostic test during my initial phase of teaching and was shocked to see that the students of grade six could not even pass the test of grade two.”

Nepal is not a poor country; it is a poorly managed country. There are political outfits in the country that constantly complain about the widening gap between public and private schools, try to close private schools down and sometimes even plant bombs in them. Instead of indulging in such futile and even destructive acts, the focus should be on improving the existing situation. In the long run, Nepal can have a free education system like in Finland, Norway, Sweden and Germany. But for now, Nepal needs to enhance and monitor the existing education system. The government should tap the huge resources at the country’s disposal and discover and nurture the raw talent of its young people that is hidden because of poverty and lack access to good educational opportunities. It should create an enabling academic environment for youths to study. Students should be politically aware, but politics should not be a hindrance to education.

Silwal is Vice President of Leo Club of Kathmandu Central Town

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu