Opinion

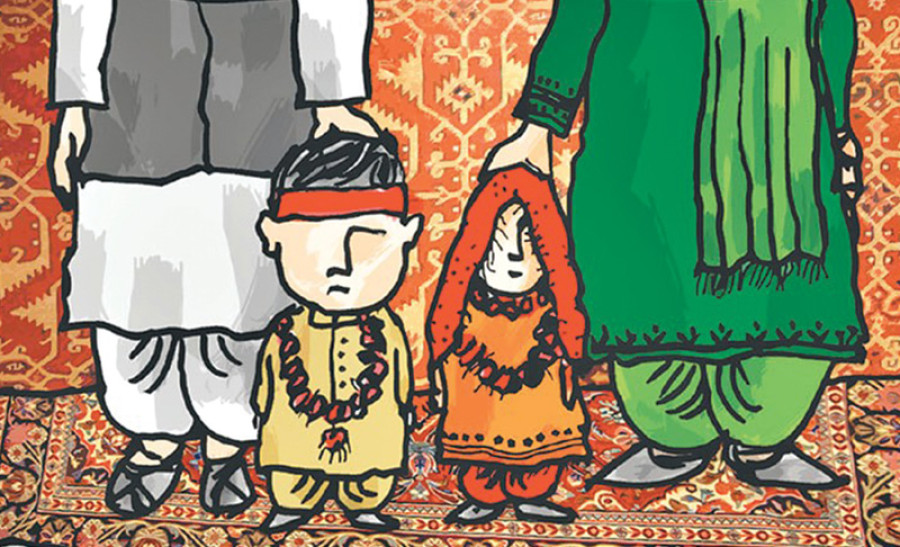

Too young to marry

On October 22nd 2016, the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare and a host of international donors marked the International Day of the Girl Child.

Sarah Rich-zendel

On October 22nd 2016, the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare and a host of international donors marked the International Day of the Girl Child. The focus was on child marriage. The speakers and participants discussed Nepal’s troubling child marriage statistic—37 percent of girls are married by the age of 18—which they attribute to the harmful practice of dowry, rooted in the social perception that girls are an economic burden on the family.

The stage, lined with honoured guests, most of whom were men, saw one speaker after another, from the ministry to community organisations, declare their commitment to protecting Nepali girls from early marriage. Their recommendations included a catalogue of technocratic and fundable solutions: awareness raising, strengthening and enforcing policy, and more education for girls. Each speech was punctuated by the worst-case child marriage scenarios articulated through dance. At the centre of the event hall was Ashmina Ranjit’s Red Glass Dress. The dress served as a euphemism for what all the participants seemed intent on ignoring: at the heart of child marriage is the control of female sexuality.

Pre-marital sex

The Ministry’s own Event Report, summarising key findings from community-based focus groups, alludes to the relationship between child marriage and a girl’s sexuality. It references parents’ fears that their daughters will have premarital “relationships” or take a “lover” and defame the family. Even more ubiquitous was the trend of adolescent “elopement” and “love marriage” self-facilitated by increased access to social media. “Technology, mainly the internet (Facebook) and short text messaging [contributes] to child marriage as adolescents communicate amongst themselves more easily and enter into relationships themselves.” The report aligns with other research that finds pre-marital sex is on the rise in Nepal. Despite these findings, there was no direct mention of sexuality anywhere in the report or at the event. Even more troubling was that none of the Ministry’s recommendations reflect the links between female sexuality, pre-marital sex and child marriage found in their own data.

If the Ministry wants to alleviate child-marriage, it must address the particular ways that premarital sex impacts a girl’s life. In Nepal, a girl’s virginity is highly prized and tightly controlled. This makes girls particularly vulnerable to policing and surveillance when faced with the natural adolescent quest to explore one’s sexuality. Until marriage, a girl’s social status is under constant threat by everything from immodest dressing, staying out too late, walking around with an unrelated male, and even being a victim of sexual violence. In fact, Meri Saathi, a sexual health helpline, notes that the primary reason young women call is for assistance handling sexual propositions outside of marriage.

Burden of honour

In Nepal, marriage is the most sacred social institution and, other than having children, marks the most important point in a woman’s life. Marriage is also the only socially permissible route for women to engage in sexual activity without undue risk to her social status. It is no wonder then that families and girls themselves feel the need to marry early. In fact, given the social pressure girls face to protect their virginity until marriage, it seems the only practical thing to do.

If Nepal wants to seriously address child marriage, it needs to seriously address premarital sex and female sexuality. The Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare would do well to acknowledge that focusing solely on the economic causes of child-marriage is short-sighted. If child marriage is caused by the harmful perception that girls are a burden, the burden is both an economic and a moral one.

Instead of raising the marriage age to 20 and increasing the number of people you can count under Nepal’s alarmist child marriage stat, maybe it is time to endorse comprehensive sexual education that promotes female sexual autonomy. Perhaps we should discourage the social policing of girls’ bodies and instead encourage safe and responsible attitudes towards pre-marital sex. To end child marriage, we must remove the collective burden placed on the bodies of girls to carry their families’, and the nation’s, honour.

Rich-Zendel is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto, Canada

14.09°C Kathmandu

14.09°C Kathmandu