Opinion

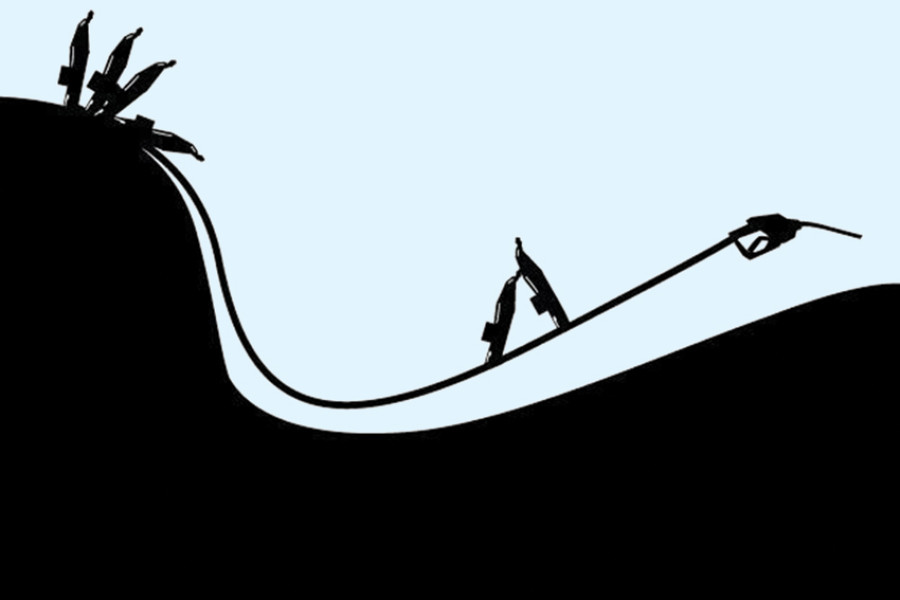

A twist in the pipeline

Nepal’s energy dependence on India will continue to constrain its ability to negotiate bilateral issues

Bibek Raj Kandel

Nepal’s recent fuel crisis originated from the unofficial Indian blockade. The country’s subsequent attempt to cement closer ties with China brought more domestic and foreign policy riddles to the country. Recent turn of events pose a number of questions. How would the KP Oli government have dealt with the Madhesi protestors had the blockade not been there? Would PM Oli have visited China before India? What different measures would the Madhesi protestors have adopted to show their dissent over the recently promulgated constitution, if the country was completely energy sufficient? There are no easy answers to all these questions, but they are all entangled in Nepal’s sole dependence on India for petroleum imports and its long-standing inability to exploit domestic energy potential.

While the Madhesi issues primarily stemmed from the dissatisfaction over the proposed federal division of the states and power-sharing in the country’s new constitution, Nepal’s crisis grew deeper when India sided with the protesters by tightening the fuel supplies. India is by far the largest trading partner of Nepal accounting for 64 percent of its foreign trade. The Indian Oil Corporation (IOC) is the sole supplier of petroleum products to Nepal. As it started cutting off supplies to Nepal, the fuel crisis started to hurt the economy severely, giving rise to black marketeering, a sudden hike in commodity prices and eventually a decline in development activities. Various sectors of the economy as well as reconstruction efforts suffered under the crisis.

Help from the north

Despite Deputy Prime Minister Kamal Thapa’s trips to New Delhi to persuade it to lift the blockade, IOC continued to slash supplies. As the Nepal government was heavily criticised for failing to abate the crisis, it was left to seek every potential alternative and assistance from every possible direction. Despite the abundant potential of home-grown generation with arguably over 40,000 MW of hydropower potential from its water resources alone, Nepal’s energy situation is quite depressing. Around 30 percent of the population still does not have access to electricity and even those with access suffer from as much as 15 hours of power cuts a day. On the other hand, supply side constraints and policy inconsistencies are putting stress on hydropower projects under construction. The message is clear: Nepal lacked the ability to deal with the recent fuel crisis without external assistance.

China came to Nepal’s rescue, providing 1,000 metric tones of oil in grant as a symbolic gesture to cope with the gloomy fuel situation. Nepal on its part was more willing to explore possibilities of obtaining fuel from China on a long-term basis and keen to enter an oil trade agreement to import as much as one third of its fuel supplies. Many applauded the move as an attempt to end the Indian dominance on petroleum supplies to Nepal. And, that stirred new foreign policy debates in both Nepal and India. Certain section of Indian parliamentarians, media and foreign policy experts in New Delhi accused the Indian government of pushing Nepal closer to China while unnecessarily trying to micromanage Nepal’s internal affairs.

However, the difficult mountainous trade routes, logistic hurdles and high cost of trade made it hard to bring in fuel from China. On the other hand, the Nepal government’s distress was visible, as it was also worried that a new deal with China might worsen its ties with India, which could impose a tighter blockade.

Dependence continues

The likes and dislikes of Nepal’s southern neighbour are often speculated to be the fulcrum of the stability of every government in Nepal. Evidently, more than dealing with the Madhesi leaders at home, the Nepal government was busy sending its envoys and using its diplomatic channels to woo New Delhi. China may also have been a little sceptical of Nepal’s aberrant diplomatic exercises and political inconsistencies and assumed that Nepal would eventually return to the status quo. Nepal energy’s crisis turned out to be a new triangular foreign policy conundrum between Nepal, India and China.

When viewed in light of Nepal’s long-time fuel dependence on India, the recent crisis, however, is less surprising. It is reminiscent of a similar episode of 14 months of Indian blockade of Nepal in 1989. Nepal had a relatively moderate growth rate of over 7 percent in 1988, which later dropped to about 4.3 percent in 1989. But Nepal had relatively smaller fuel dependence in 1989 than it has today. That gave a bit of a breathing space to the then Prime Minister Marich Man Singh Shrestha to negotiate bilateral issues with India and was probably the very reason Nepal somehow managed to survive a blockade for over a year. A lot has changed in between. There has been an increase in Nepali population by 10 million and a four-fold rise in per capita petroleum consumption-from 0.01 kg to 0.04 kg of oil equivalent—since 1989.

With the recent 80 MW power import deal with India and plans to import an additional 580 MW by next year, this huge energy dependence will continue to constrain Nepal’s ability to negotiate any bilateral issues with India and could further limit its capacity to maintain a balanced relationship between China and India. The bleak energy situation at home and the dependence on India would neither allow Prime Minister Oli to comfortably negotiate past treaties and agreements with the southern neighbour, nor discuss other bilateral issues, let alone question the recent blockade. Like most of the previous visits of Nepal’s prime ministers, it will be another ‘friendly visit’, which the Nepal government will invariably claim as having set a new milestone in the history of Nepal-India relations.

Kandel is a national advisor at Alternative Energy Promotion Centre; views expressed here are personal

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu