Movies

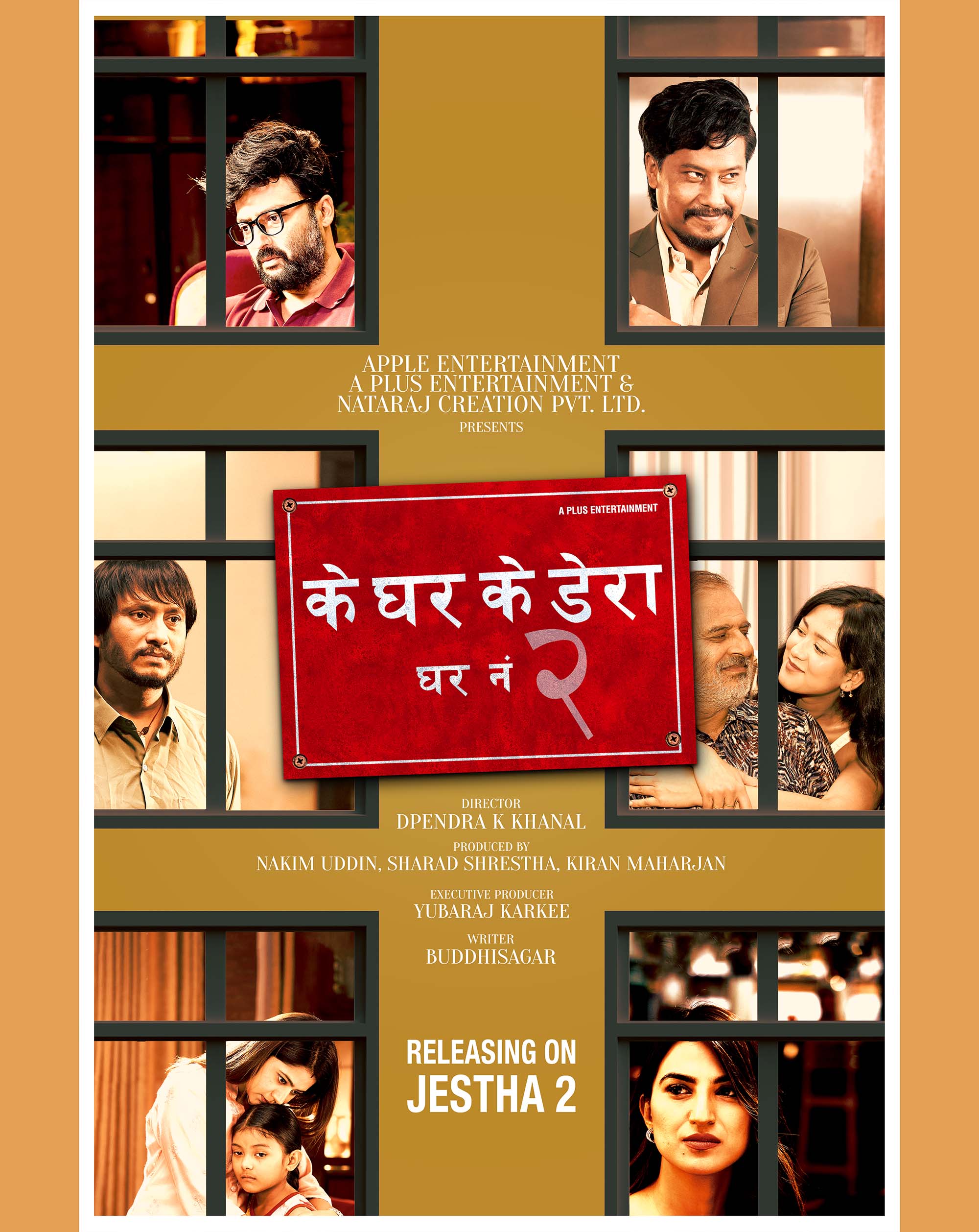

In ‘Ke Ghar Ke Dera: Ghar Number 2’, beleaguered businessmen and benevolent saviours

The film makes a sincere effort to portray characters struggling financially amid post-pandemic recession. But a contrived resolution highlights the film’s uninspired political imagination.

Timothy Aryal

The title may have one guess the film is about landlord-tenant dynamics but there’s little of that here. Instead, it’s about how various economic shocks in republic Nepal have left no one untouched, be it the landlords or the tenants.

The subtitle refers to the fictional Raunak Niwas, a two-storey brick-and-cement building at some Babarmahal Marga neighbourhood in Kathmandu, which houses most of the film’s major characters. The building is an old one. It has lately started leaking, leading to electric short-circuits and frequent power outages. Not so long ago, a dead rat got stuck in its drainage, forcing its inhabitants to use the neighbours’ toilet. Owner Raunak Thapa (played by Aryan Sigdel), a serial entrepreneur approaching middle age, could have sold this house and bought a newer one. But it holds an emotional value for him: it was passed down by his father, telling him its walls were not mere concrete but rather like his skeletons. So even while Raunak has a bank loan pending, he doesn’t sell it. Even after the bank has blacklisted him, publishing his name on the national daily. This has led to a frosty relationship with his wife, Reecha (Keki Adhikari). There’s a lot at stake here, and not just for Raunak; all other major characters of this drama are struggling one way or the other amid the post-Covid recession.

‘Ke Ghar Ke Dera: Ghar Number 2’ marks director Dipendra K Khanal’s 13th feature film. Khanal is known for social dramas that satirise existing socio-political realities and challenge stereotypes, with varied degrees of success. In his new outing, with a screenplay by Buddhisagar, the novelist of the ‘Karnali Blues’ fame, Khanal has branched out to tackle a socio-economic subject with a story set sometime after the coronavirus pandemic. The film brings to screen characters wrestling with all too familiar economic issues. Lives are on the line. One character attempts self-immolation in front of Singhadurbar, in what is a reference to Prem Prasad Acharya’s self-immolation in 2023. The film hence touches upon a sensitive subject that is starkly political.

The characters of this film can be broadly divided into two categories—those who have been dealt a hammer blow by the economic crises and are struggling to get back on their feet; and those who are starting small.

The former lot includes an ex-businessman (Prakash Ghimire), who gets an anxiety attack upon hearing the word ‘pyaj’—onion—for he lost a truckload of onion and vegetables imported from India after the 2015 border blockade. He then went bankrupt. Then there is Diwakar (Nischal Basnet), who is hounded by a loan shark (Sanjog Rasaili) and his henchmen. Having failed to pay back the loan he took to start a business, Diwakar is harassed and assaulted. Another character of this lot includes the owner of Raunak Niwas himself, whose stints at a travel agency and then at the stock market have landed him knee-deep in debt. And the house that he holds so dear is on the line.

Among the latter lot are those who are starting small, struggling to find their place in an unforgiving city. Rajaram (played by Khagendra Lamichhane) gets by doing whatever comes his way—from repairing umbrellas to tailoring. His industriousness and a series of freak incidents help him climb the income ladder. Another character of this lot is Puja (Upashana Singh Thakuri), the ex-businessman’s daughter, who manufactures pillar candles at home to sell it online.

The script appears aimed at striking a balance between the two types, between despair and hope, it seems; the desperation of the former lot is counterbalanced by the diligence of the latter. And to some extent, it succeeds.

‘Ke Ghar Ke Dera: Ghar No 2’ is perhaps the first Nepali feature film to be set in a post-Covid time. It is aware about the political nature of its characters’ woes. The ex-businessman says that everything revolves around politics, whether one wants it or not. The film even portrays an insensitive, indifferent finance minister who brushes off the Covid-induced recession, saying it’s happening not just in Nepal but around the world, conveniently ignoring the fact that some economies have dealt with the pandemic’s aftershocks better than the others. Yet, the film is not interested in finding a political solution to their problems, resorting instead to a tired trope just for a happy ending.

The film takes a disappointingly fatalistic course in its final quarter, mirroring Nepalis’ obsession with a strongman saviour to appear out of nowhere and rescue the country from its ills. The film portrays all the elements that are necessary for a political explosion; just think of why so many youths recently rallied behind Durga Prasai. Rather than having its characters meekly submit to their fates, the film could have had them organise politically, or at least, rant on social media, so to speak.

But the film reaches its denouement by introducing saviours out of the blue who rescue its beleaguered characters turn by turn.

This film is thus a missed opportunity to portray the confusions of republic Nepal, especially after the pandemic. That, however, is not to say that the film fails on all fronts. There are certainly some contrivances here that could have been done away with (including the loan shark character’s mock gay speech), but the film makes a worthy attempt at providing a snapshot of the period it’s set in. While it is often mawkishly sentimental, it is also sometimes funny. And though it feels like a missed opportunity for Buddhisagar to present a sharper reflection of our time and make a splash with his screenwriting debut, there’s promise in his endeavour. I look forward to his next one.

8.65°C Kathmandu

8.65°C Kathmandu