Movies

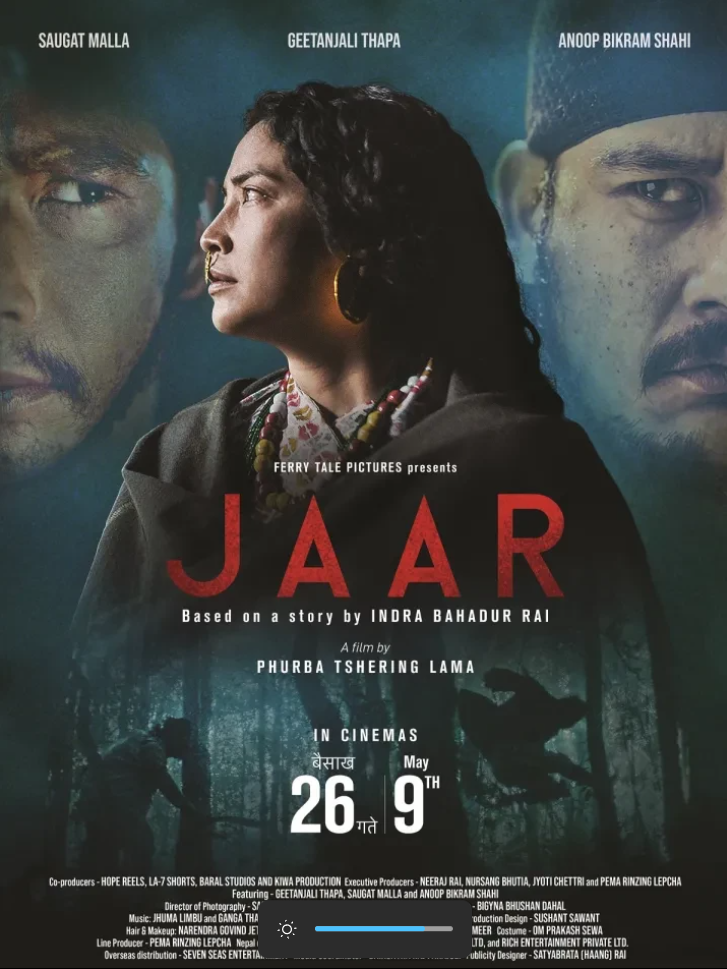

‘Jaar’: A sensuous adaptation

The movie takes viewers on a quiet, powerful journey through history, tradition, and personal rebellion—all without heavy dialogue or drama.

Prashanna Mali

‘Jaar’ begins with a wide, painting-like shot of a landscape. A boat slowly carries a group of people across the water. The scene plays out in one continuous take, emphasising how long the journey is and how important it is in the country’s history.

The movie ends (no spoiler) with people sailing away from a similar place, something the film highlights powerfully. A lot seems to happen in between, but not much actually does. Time passes, a rebellious act takes place, and a historical moment is shown. But did it change anything in society or the nation? Or was it just a personal moment? You must watch—or rather, feel—the film to decide for yourself.

Based on a well-known story by writer and critic Indra Bahadur Rai, ‘Jaar’ took many years to be made into a film. Even after it was completed, it took a few more years to be released. Directed and adapted by Phurba Tshering Lama, it is one of the few Nepali films based on a short story.

The film tells its story like an experimental yet classic book, using chapters, text, and artwork on black screens. The title credits cleverly show the political history of that time.

It features rooted music, beautiful painting-like shots, camera movements that flow with the music, a realistically portrayed tiger, rich sound design, local dialects, and simple but effective costumes and sets. Together, these elements create a powerful visual experience that takes us back to 1890s Nepal—without needing much dialogue or explanation.

The 4:3 aspect ratio lends well to seeing things from a distant perspective and feeling the minimality. The image quality and colour correction have yesteryear vibes, like those captured from the earliest colour cameras, adding a nostalgic and rooted sensory atmosphere to the viewing.

We experience most of the film through Thuli’s perspective, played gracefully by Indian National Award-winning actor Geetanjali Thapa. She comes across as a woman trapped in the wrong era, and her pauses and silences show the emotional weight she carries.

Instead of focusing on social issues, the film explores the psychological—and sometimes even leans into horror, though these elements stay in the background. The central external conflict arises from the traditional folk custom of ‘Miteri Saino,’ beautifully shown through a bond between two young girls from the Thapa and Gurung communities. Their families come together and form a sacred friendship pact, which sets the story in motion.

The two also carry a hint of rebellion (as seen in a forest hiding scene) but remain trapped within a larger system. The central conflict stems from the practice of Jaar Pratha, where if a married woman takes another lover, that man is labeled a Jaar. Upon discovery, the husband has the right to seek justice. However, the film doesn’t portray these issues in a heavy-handed way. Instead, it focuses on the psychological toll these customs take. Everything shifts when Thuli catches a glimpse of Rudraman—portrayed with subtlety by Saugat Malla. He does very little, yet commands attention with his expressive eyes and measured vocal tone, especially during a tense confrontation with Thuli.

As ‘Aye Thuli’ by Jhuma Limbu plays, we witness her growing infatuation with him. Time seems to pause—for her and for us—evoking the iconic mood of Wong Kar Wai’s ‘In the Mood for Love’. Harshajit, played by Anoop Bikram Shahi, is introduced through sound, and the contrast is striking—his presence carries more menace than warmth. Shahi’s imposing physique and voice are used sparingly but effectively. Here, sound and music are as powerful—if not more so—than visuals. The use of period horror sound effects keeps the film grounded while subtly introducing genre elements and expectations.

During a confrontation scene of major characters with a tiger, the wild animal’s roar is so sharp and lively that it shook me from my seat. Thuli’s own roar is just as powerful when she commits her act of violence. Whenever the film risks slipping into melodrama, it jolts us with something brutal, something unexpected. It might be the cutting of an animal part, or an attempt to slice a human. The horror is established early, making the appearance of the VFX tiger feel less like a gimmick and more like a natural, earned moment.

The film’s pace may not be for everyone—it often settles into an almost meditative trance, deliberately lingering on each image to emphasise power dynamics within the frame. In one striking scene, an important discussion unfolds while Thuli remains in the background, visually present but voiceless. She is ignored despite repeated attempts to gain approval from a more ‘powerful’ figure. The framing and sound design in this moment effectively convey how the voices of vulnerable groups are often unheard or simply dismissed.

There are some underwhelming aspects, such as excessive fade-outs, abrupt narration, and unresolved relationships. Although the tiger sequence features authentic VFX, it lacks consistent horror and suspense. The film also misses internal tension between major characters, weakening its emotional impact. Still, to the film’s credit, it shows how social realism and literary adaptation can create a unique cinematic experience when done with minimalism and strong genre craftsmanship. It also highlights where Nepali cinema’s new challenges lie after ‘Purna Bahadur Ko Sarangi’.

Jaar

Director: Phurba Tshering Lama

Cast: Saugat Malla, Anoop Bikram Shahi, Geetanjali Thapa

Language: Nepali

Running time: 1h 55 minutes

20.72°C Kathmandu

20.72°C Kathmandu