Movies

Matriarchy, social structure and rituals

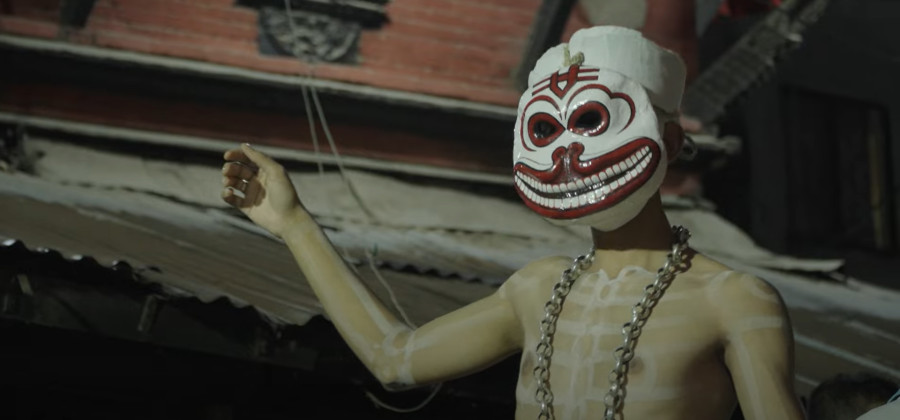

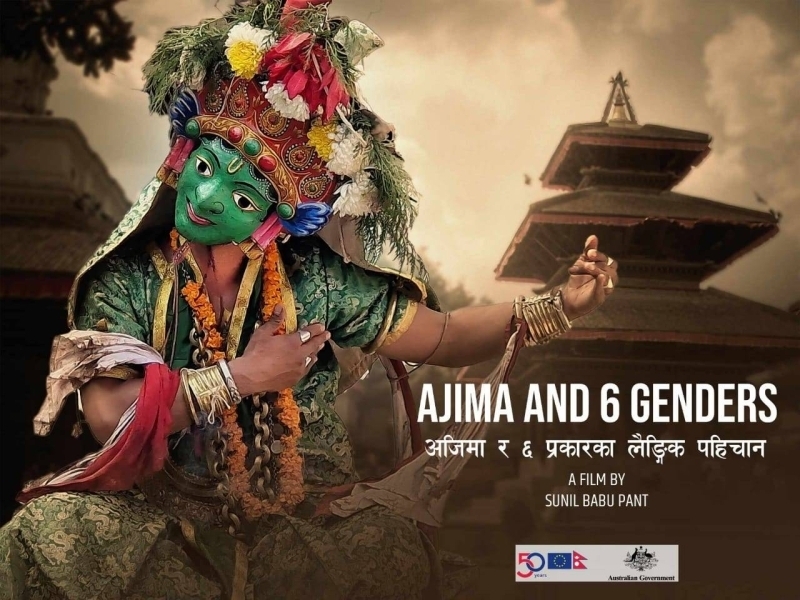

Sunil Babu Pant’s ‘Ajima and 6 Genders’ explores the transition from matriarchy to patriarchy in Kathmandu’s history—and its implications for gender issues.

Sanjeev Uprety

Recently, I had an opportunity to watch ‘Ajima and 6 Genders’, a film by Sunil Babu Pant, the founder of Blue Diamond Society, fighting for the rights of the LGBTQI community.

The film shows that the matriarchal society inside the Kathmandu valley, as reflected in Licchavi iconography and rituals, was displaced by patriarchal civilisations that came later.

‘Ajima and 6 Genders’ invited a lively exchange during the panel discussion, attended by two politicians, Aahuti and Bimala Rai Poudyal, and moderated by Meena Poudel, a sociologist, researcher, and activist.

Aahuti argued that the film’s narrative overlooks the tools and relations of economic production and the institution of private property, which were instrumental in transitioning from a female-dominated society to a male-dominated society. During the Q&A sessions, some other critiques of the film were also raised.

Sachin Ghimire, a medical anthropologist and filmmaker, noted that the film neglects the archaeological aspect of the societal shift (from a female-dominated society to a male-dominated society) and that, for this reason, the filmmaker’s “subjective claims and his epistemological know-how” should be questioned. Some others in the audience questioned the historical authenticity of the narrative presented by the film.

For my part, I enjoyed the film for two reasons: firstly, it made me rethink the city spaces, including those of Thamel, Naradevi, and Basantapur Durbar Square, among others, and see those familiar spaces from new, unfamiliar perspectives.

It was instructive to know how women-centred rituals and images, often half-forgotten, are shimmering around us as new layers of history, mostly men-centred, are superimposed upon the urban surfaces with the passage of history.

Secondly, the narrator (filmmaker Pant himself) does not claim to present a factual history. Instead, he acknowledges that his narration is a matter of personal interpretation and may be incorrect. In other words, the narrator foregrounds his insecurity and uncertainty during narration. This makes the film open-ended, inviting further research and questioning rather than providing clear, definitive answers. This was the film's strength, as reflected in the lively Q&A session, which prompted people to explore new inquiries rather than be satisfied with conclusive, exhaustive answers.

The film straddles a middle ground cut across by the contradictory impulses of political and mythological/spiritual desires. By depicting mythological, cultural rituals celebrating women and members of the LGBTQI community, it provides strength and impetus to the current struggles waged by women and LGBTQI activists fighting for equality.

At the same time, however, its recourse to cultural practices rooted in mythology leads the narrator to make sweeping pronouncements, such as that the living goddess Kumari should be made the president of Nepal, a statement that many might find objectionable, especially if this cultural practice is examined from the angle of child rights perspective.

The film shows that patriarchal cultures represented LGBTQI people and Indigenous people of the Kathmandu Valley as rakshasas, devils, and pishachas. While I found this interesting, it made me wonder if the caste system, too, was involved in such cultural othering.

In other words, if the caste system entered Nepal with Licchavis (as rightly pointed out by Aahuti), isn’t it possible that those who were placed at the bottom of the social hierarchy in terms of division of labour, the so-called untouchables in other words, were also represented in the same way— as rakshasas, asuras or some other “devilish” unruly elements that were a threat to the state apparatus and social order of those times?

The film also valorises matriarchy and presents it as an alternative to patriarchy. But is this the right solution? The end goal of all social revolutions and movements is a society that is neither patriarchal nor matriarchal but in which there is true equality for all, including men, women and all other genders, ethnicities, and linguistic communities.

Cultural texts depicting women-centred practices, including the film under discussion, can function as strategic tools to challenge the structure and ideologies of patriarchal society; however, such representations should not valorise one type of hierarchical power structure above another.

What we need is a social structure that is horizontal rather than vertical, one that welcomes and celebrates all kinds of differences, including differences of culture, language and gender, among other socio-cultural differences.

When I returned home after watching the film and the subsequent discussion, my mind kept ringing with all these concerns and questions. This reflects the film's success, inspiring viewers with new questions about history, cultural practices, gender, and sexuality. This is certainly no mean achievement in a society where the ability to ask critical questions quickly dissolves in the tangle of unthinking name-calling and new rituals of commodity culture.

Ajima and 6 Genders

Filmmaker: Sunil Babu Pant

Year: 2024

15.87°C Kathmandu

15.87°C Kathmandu