Movies

Revisiting ‘Jhola’: Social commentary done right

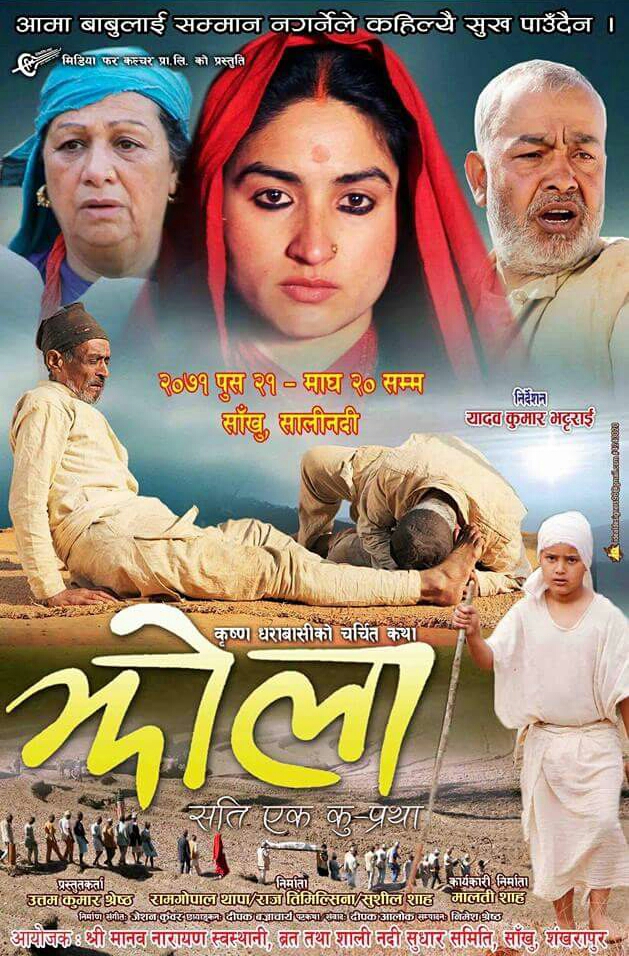

Released in 2013, the film steered away from the didactic tendencies of social dramas to reveal the complexities of the ‘sati’ tradition and its effect on women.

Kshitiz Pratap Shah

‘Jhola’ has a special place in the history of Nepali cinema. Almost unanimously revered and even nominated as Nepal’s Oscar submission in 2014, it is seen as an outlier in its unique addressing of a dated yet complex social issue. When I first watched it as a 13-year-old (almost a decade ago), it created a stellar impression in my mind. What ‘Jhola’ did in comparison to other movies on social issues is introduce nuances to its subject matter and make us question whether we place the blame on the right entities for such social evils. Instead of leaning into melodrama and simplification, the movie, for me, was a way of questioning a linear, black-and-white way of thinking back then. Now, when I rewatched the film nearly after a decade, I still feel that a great part of that authentic, even challenging essence of the movie still remains.

‘Jhola,’ based on Krishna Dharabasi’s short story of the same name, follows a small family from the rural hilly region of Nepal in the 1940s. Our protagonist (Garima Panta) is identified not by her name but simply referred to as Kanchhi. Her husband (Deepak Chhetri) is nearly thrice her age and is on his deathbed. Kanchhi also has a young son (Sujal Nepal), who often acts as the audience’s surrogate in the movie. Between father and son, Kanchhi is shown as the all-caring mother, responsible for everyone’s well-being. In fact, we get to see this family dynamic for nearly a third of the film and focus on the love given to Kanchhi by these two. We are concerned not only for her well-being, or due to a moral obligation, but also because we realise how the ‘sati’ tradition—which mandated that a woman burn along with her dead husband—immediately and permanently breaks familial bonds apart.

Kanchhi’s husband insists on not letting Kanchhi go to ‘sati.’ He understands just how young she is and presents this wish to her and his young son personally. Yet, this idea, constantly appealed to by the son during the funeral, feed into deaf ears. The cultural links associated with the system are entrenched to the point of being detrimental. ‘Jhola’ thus showcases how even the perpetrators of the ‘sati’ tradition are merely enacting a deep-set norm in the social conscience, which reveals that the issue of ‘sati’ transcends personal morality.

One of the few moments where the movie falters is during the death of the father. While we know enough about Kanchhi and the issue at hand to feel sympathetic towards her, the funeral scene, in particular, relies more on telling rather than showing. We see the sister-in-law (Laxmi Giri) side with Kanchhi while consoling Ghanashyam, the son. Yet, her complaints about the hypocrisy of the ‘sati’ tradition feels like a modern insertion, something added in hindsight. While theoretically valid and poignant, the movie rarely visualises her ideas until the end, where we see the extent of the tradition through violence on another ‘sati’ victim.

However, ‘Jhola’ remains personal and grounded for the most part. A large part of this is due to the acting of the two leads. Panta as Kanchhi is toned down, but it works great. She seems not merely a victim but also someone capable of carrying the familial weight on her shoulders. She plays Kanchhi as someone experienced and emotionally stable beyond her years. This doesn’t mean her character doesn’t emote at all—there are scenes where she gives her all. Her crying after the death of her husband is one such moment, a rare instance where Kanchhi breaks down, dismantling the shield she has constructed so well so far.

Similarly, Sujal Nepal brings relatability to the character of Ghanashyam. His character shows compassion and loyalty to Kanchhi, but he rarely overplays his part.

The screenplay uses metaphors, flashbacks and dream sequences to its advantage. The dying father’s dream of seeing himself in fire foreshadows the burning of his wife and the sudden change it brings to his family. Yet, these additions also break the monotony of the present and justify character motivations in a refreshing way.

Most importantly, though, the movie structures itself to be constantly linked to the present, as we see the story of Kanchhi and Ghanashyam play merely as a flashback to the turmoils of suspicion, doubt and unjustified violence in the middle of the Maoist insurgency. Dharabasi, the author of the short story, also makes an appearance, largely to remind us how contextual such discriminatory social evils still are in our society.

In fact, the dowry system, chhaupadi and witch trials still happen in Nepal. The ending is bitter-sweet (and perhaps even ironic), as Dharawasi pays homage to Chandra Shumsher, who allegedly abolished the ‘sati’ tradition but led an oppressive regime that was plagued by other forms of exploitation. This juxtaposed ending ultimately does a great job of leaving the audience at an edge—forcing us to come to terms with the deep-set rot of injustices lodged into our social systems.

Jhola

Language: Nepali

Released: 2013

Available on: YouTube, with English subtitles

Duration: 1 hour 30 minutes

Director: Yadav Kumar Bhattarai

Cast: Garima Panta, Desh Bhakta Khanal, Sujal Nepal, Laxmi Giri and Deepak Chhetri

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu