Investigations

A Madhesi died in police custody. No one knows what really happened

Ten days after his arrest, the family was told that Ram Manohar had died in police custody. Police officers in Bardiya said that Ram Manohar had collapsed in prison and had been rushed to Kathmandu for treatment, but he died on the way.

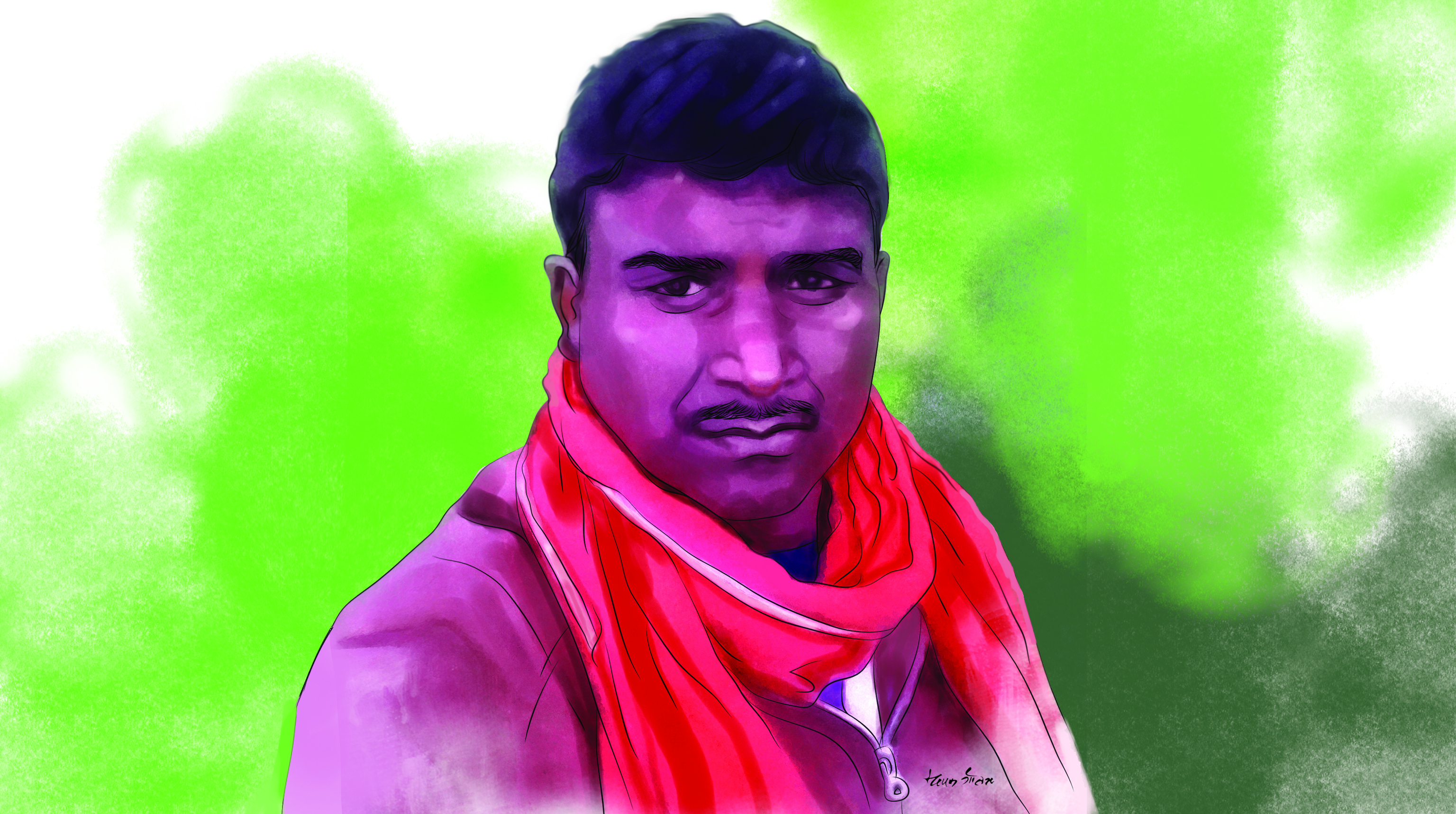

Chandan Kumar Mandal

On August 23, 2018, Ram Manohar Yadav left his home in the village of Kapasi in the western district of Banke despite his wife repeatedly pleading for him to stay home. Deputy Prime Minister Upendra Yadav was scheduled to attend an event in Gulariya, about 35 kilometers away, and Ram Manohar, along with a few friends, planned to display black flags in protest.

Ram Manohar had announced his intentions on Facebook a day earlier, writing a post criticising the Federal Socialist Forum leader as ‘anti-Madhesi’. Although a veteran Madhesi leader and architect of the 2007 and 2008 Madhes Movements, Upendra Yadav, since moving to Kathmandu and joining the government, was increasingly being seen as someone who had betrayed the Madhesi cause—by joining the incumbent KP Sharma Oli-led government, which is widely seen as being less than sympathetic to marginalised communities.

Sunita, his wife, said she had a gut feeling that something unpleasant might happen. “I tried my best to stop him but he didn’t listen,” she recalled in an interview with the Post. “He said he would return in the evening.”

Ram Manohar didn’t return that night. He and three others had been detained by the police during their peaceful protest at Gulariya.

This wasn’t the first time Ram Manohar had been arrested. The 30-year old Free Madhes activist, who in recent years had turned into an ardent supporter of the secessionist movement leader CK Raut, had been arrested at least three times in the past for his involvement in the campaign for a separate Madhes. So, the family thought he would be back home sooner or later—just like all the other times he’d been taken into custody.

Only this time was different. Ram Manohar would never come back home.

Ten days after his arrest, the family was told that Ram Manohar had died in police custody. Officers at the District Police Office in Bardiya said that Ram Manohar had collapsed in prison and had been rushed to Kathmandu for treatment, but he died on the way. Madhesi and human rights activists, however, alleged that Ram Manohar died due to mistreatment and a failure to get him medical attention in time, leading to an investigation by the National Human Rights Commission .

All photos from Yadav's Facebook page

***

For those who knew him well, Ram Manohar was not always obsessed with politics. He was a quiet man who mostly kept to his own affairs.

“He was an ordinary person just like everyone else—a family man,” said Bishnu Yadav, his younger brother. Ram Manohar didn’t have so much as a single bad habit and the entire village of Kapasi in Banke’s Janaki Municipality knew him to be a decent man, Bishnu said.

Ram Manohar had excelled in school, and passed the daunting School Leaving Certificate exam in 2008 when Bishnu himself had dropped out. But while others in his village, including his brother, chose to migrate abroad as labourers, Ram Manohar graduated from high school and stayed back home. After Bishnu left for Malaysia for work, the elder Yadav took care of the family, working on their farm and running a small grocery store.

“I repeatedly asked him to join me abroad but he refused,” Bishnu said. “Had he listened to me and left the village, he might’ve been alive today.”

Wave after wave of Nepali politics passed Ram Manohar by, as the 2006 People’s Movement and the two subsequent Madhes Movements, in 2007 and 2008, came and went. He was never interested in demonstrating or protesting. Even in 2015, when the third Madhes Movement blazed across the plains in protest of the new constitution, Ram Manohar mostly stayed home, said family members. Friends and neighbours burned the new constitution, alleging discrimination against Madhesis—what they saw as one more thread in a centuries-old pattern of prejudice.

It was in the aftermath of the third Madhes Movement that Ram Manohar started to take an interest in politics. The new constitution—although greeted with widespread protests across the country, especially in the Terai plains—had been promulgated and the protests met with violent suppression by the state. In the clashes that followed, over 52 people died, including 11 security personnel.

Just as heated ethnic debates took over national discourse, Ram Manohar gradually began to veer towards Raut’s secessionist movement, said Bishnu. The latest in a string of movements demanding a fairer share in governance and administration had been met with the jackboot of the government, and this left a deep imprint on Ram Manohar’s mind. Although Madhesis had protested time and again for federalism and a new constitution, a statute that actively discriminated against them had been passed, and the politicians they had put faith in had betrayed them.

Family and friends who were close to him said Ram Manohar desired an alternative force that could save Madhesis from discrimination and he found that alternative in CK Raut. He first began following Raut, who was already gaining popularity among Madhesi youths, on social media.

One afternoon in December 2015, when the third Madhes Movement was at its peak, Ram Manohar met with Abdul Khan, leader and spokesperson of the Alliance for an Independent Madhes, at a garage in Nepalgunj. During that meeting, Ram Manohar expressed his grievances and an interest in joining them. They exchanged phone numbers.

Khan and Ram Manohar began to communicate regularly about the discrimination they were subject to and their personal experiences of ill treatment.

“He would complain that all his life he had served the community as a volunteer for the Red Cross and by operating a children club in the village,” Khan told the Post in an interview. “But whenever he left his village or went to any public office, he would be treated differently because of his colour and the community he represented.”

Khan said Ram Manohar was a man who believed in freeing the Madhes from ‘state-sponsored discrimination’.

On January 29, 2016, during a rally in Nepalgunj, Ram Manohar, along with a group of youths from his village, formally joined the Raut movement, according to Khan. After that, he became an active campaigner.

Bishnu learned of Ram Manohar’s newfound political consciousness through Facebook, where the latter would openly write posts about his desire for a separate country for Madhesis and his support for Raut.

Ram Manohar’s family was distraught over his decision to follow Raut. The University of Cambridge-educated computer scientist-turned-political activist had become a lightning rod for police action, given his openly seditious stance. By 2015, he had already been arrested multiple times and was constantly under police surveillance. In parts of the Madhes, though, Raut was being hailed as a hero who was willing to go where most Madhesi leaders never dared. Ram Manohar’s support for such a controversial leader worried his family that he might be inviting unwanted attention from the government.

“I had repeatedly told him to stay away from Raut as nothing would ever change for Madhesis like us,” Bishnu recalled telling his brother over the phone from Malaysia.

Ram Manohar would tell Bishnu that once they achieved their goals, no one would have to leave the country for work. He believed that if the Madhes separated from Nepal, it would bring an end to the deeply-entrenched discrimination that Madhesis undergo. “People like you can return home and work here forever. I, too, can die here in my own land,” Ram Manohar told him, Bishnu said.

Even in the Madhes, Raut represents an extreme. Leaders who were once considered radical, like Upendra Yadav, had softened their stances since joining government. Bishnu said he believes the rampant discrimination and humiliation against Madhesis led Ram Manohar to join a secessionist movement.

“We all know how things are for Madhesis,” said Bishnu. “Otherwise, why he would join?”

Yadav became an ardent supporter of CK Raut after the third Madhes movement.

For Madhesis in Nepal, it has always been an identity crisis. Most residents of the southern plains say they have been treated as second class citizens all their lives. The 2007 movement might have helped the Madhesi agenda reach Kathmandu, but their major demands—bigger representation in political, economic and bureaucratic spheres that have been historically dominated by upper-caste people from the hills—remained unaddressed.

The third Madhes Movement against the constitution was brutally suppressed but it bought Madhesis some concessions. But after the first amendment in January 2016, Madhesis felt betrayed by their own leaders, whom they accused of once again becoming part of the same old system that discriminated against the Madhes and its people. The amendment was inadequate, they said, and betrayed the spirit of the protests.

Amid all this, Raut's movement, arguing there was no other way Madhesis could secure their rights until there was a Free Madhes, struck a sympathetic chord among people like Ram Manohar.

Ram Manohar’s growing affinity for the Free Madhes movement particularly worried Sunita. She tried countless times to stop him from attending rallies and posting on social media about Raut.

“He would say he will only stop after gaining freedom,” said Sunita.

***

On August 23, 2018, Ram Manohar, along with two other Raut supporters, was taken into custody by the Bardiya District Police Office. He was held for a week, during which time no family members were allowed to meet him. After seven days in custody, on August 30, Ram Manohar suddenly fell sick.

“He had a terrible headache at around 5 am in the morning and collapsed inside the cell,” said Rajit Ram Verma, who was detained alongside Ram Manohar.

Police admitted Ram Manohar to the Bardiya District Hospital in Gulariya, less than 200 metres away from the police station. Once the doctors decided that the district hospital didn’t have the resources to treat him, he was rushed to the Bheri Zonal Hospital in Nepalgunj, some 37 kilometers away. Once again, the government hospital said it couldn’t treat him because it lacked intensive care facilities, so Ram Manohar was transferred to the Nepalgunj Nursing Home.

By this time, doctors said Ram Manohar had a fever of 108 degrees and was showing signs of paralysis. When Sunita reached the hospital, she only saw her husband from a distance, lying unconscious on a hospital bed, she said. That was the last time she would see Ram Manohar alive.

As his health worsened, doctors at the nursing home suggested that Ram Manohar be taken to Kathmandu in an ambulance. After a nearly 15-hour journey by road, he was brought to the Maharajgunj-based Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital. At 2.15 am on September 1, immediately after his arrival at the Hospital, Ram Manohar was declared dead.

Ram Manohar’s family and friends, however, tell a different story. In early September, Deepak Paasi, Ram Manohar’s neighbour who rode in the ambulance to Kathmandu along with two policemen and a medical officer, told the Post that Ram Manohar was already dead when he was admitted to the Teaching Hospital, contradicting the police’s statement.

Ram Manohar’s family blame law enforcement for his untimely death, and accuse the police of not taking him to the hospital on time. Although the police claim that Ram Manohar had long suffered from hypertension, family members deny he had any health issues.

“He was fit and was never on any medication,” said Sunita. “How can he suddenly fall so sick that he would die?

Sunita said she believes her husband was tortured to death and has been demanding a detailed investigation.

Verma, who was alongside Ram Manohar in the prison, told the Post that all four detainees were taken to separate rooms one by one for interrogation where the police would threaten them. Ram Manohar was silent most of the time, he said.

“The district police chief verbally abused all of us as if we were dacoits and not Nepali citizens,” Verma said. He said he was wrongfully arrested as he was not a CK Raut supporter but had instead attended the programme in support of the deputy prime minister.

According to Verma, the four of them were escorted out of the venue before the event even began, long before Upendra Yadav had arrived. They were taken away out one-by-one by the police.

“The SP [Superintendent of Police] threatened to shoot all of us at the [Nepal-India] border. He said this is not your country. You are all Biharis and deserve to be shot dead at the Indian border,” Verma said.

Verma and the other two arrested alongside Ram Manohar were later released.

For Ram Manohar’s friends and family, his death is one more instance of a deeply-entrenched discriminatory attitude that the state has long adopted towards Madhesis. One of the primary reasons behind the Madhes Movements has been this simmering anger against a state that does not see a significant section of its population as citizens.

Driven by a desire to see justice done, the Yadav family pursued a number of avenues, including human rights organisations and various government offices. Protests against Ram Manohar’s death led to an investigation by the National Human Rights Commission in early September, but the report has yet to be published.

The Nepal Police, meanwhile, has doubled down on its insistence that security personnel had nothing to do with Ram Manohar’s death. The police in Kathmandu refused to register a First Information Report (FIR) into the custodial death, saying the family needed to file it from their own district.

On September 6 last year, Bishnu Yadav returned to Banke to file the FIR. But the local District Administration Office and District Police Office refused once again to entertain their petition. Desperate, the family dispatched a petition for an FIR via post—it was returned unopened.

Meanwhile, the day after Bishnu left Kathmandu, the Nepal Police conducted a post-mortem on Ram Manohar. The Yadav family had refused to provide consent for the post-mortem unless an FIR was filed. But after the family left, police seized the opportunity to conduct the post-mortem without their consent. The family said they never received a copy of the post-mortem report, neither has it been made public.

When Bardiya District Police Chief SP Surendra Prasad Mainali was asked why the post-mortem report was not given to the family of the victims, he said the report was with the District Court.

“We submitted all the documents to the court when we had filed the case. If they wish to see the document, they can file an application at the court and get a copy of the report,” Mainali told the Post.

However, the process should not be long winded as it has been for the Yadavs, legal experts told the Post. According to law, the victim’s family should not only have access to all details regarding the case—including a copy of the post-mortem report—but should also be briefed regularly by a government lawyer on the investigation’s progress.

On social media, Ram Manohar was a regular family man, posting pictures with his wife and children.

On September 22, the family received a call from the police asking them to collect the body from the Teaching Hospital morgue, where it has been lying unclaimed for the past five months. When they refused, they said they began to receive threatening phone calls day after day.

“They asked us in a threatening tone to collect the dead body and the compensation amount,” says Bishnu. “Or else, they won’t be responsible for anything that might happen to us, they said.”

Ram Manohar’s death has permeated down to the village, where CK Raut was once a popular figure. Now, villagers warn their families to refrain from any activity linked to Raut, as they might suffer the same fate, said Suresh Yadav, ward-6 chairperson of Janaki Rural Municipality.

“Irrespective of their political affiliations, they mourn Ram Manohar’s death,” said Suresh. “His untimely death has left people in shock. There are some dedicated believers in the CK Raut movement who might be unaffected, but many families have started warning young people to stay away from Raut.”

Ram Manohar left behind three children. The youngest, three-year-old Nischal, has yet to register the death of his father, who would bring home chocolates or cookies every evening. Sunita said Nischal still believes his father remains in jail, a white lie that she has been telling him for months.

“Mother, when will the police free my father?” he regularly asks her, she said. “He has been gone for so long now.”

Read other Saturday features from the Post:

— As Kathmandu’s air gets worse, its residents struggle to breathe

— Kathmandu’s roads are widening but there’s no space for pedestrians

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu