Interviews

Trained doctors and nurses should be paid better

Government must follow up on legal obligations of the individuals who have signed contracts pledging to come back from abroad.

Thira Lal Bhusal

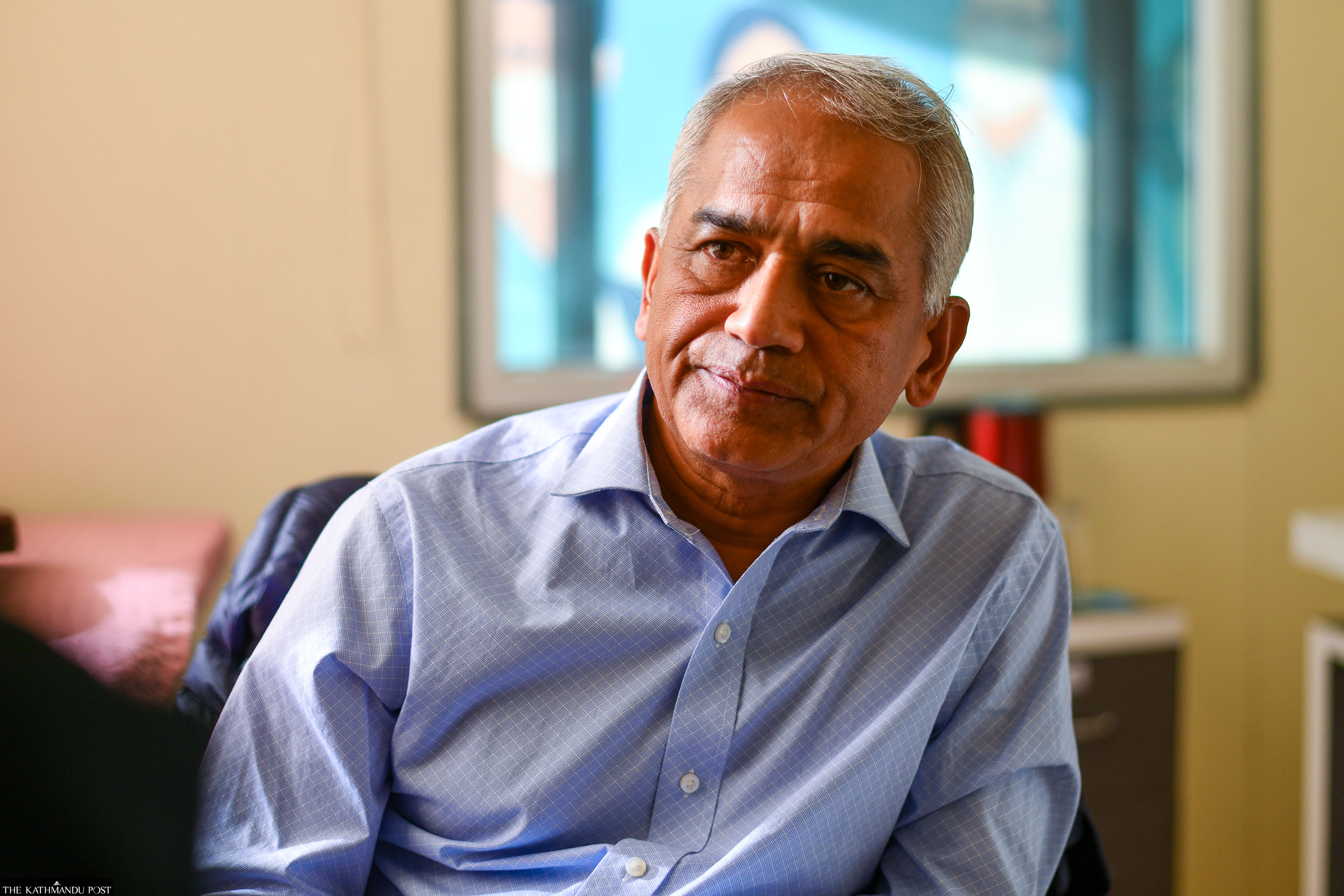

Dr Bhagawan Koirala, a pioneer in open heart surgery in Nepal, is also known for his key role in establishing the Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre 24 years ago. Koirala, who also helped establish various other health institutions, is now working on an ambitious project aiming to run children’s hospitals in all seven provinces. The Post’s Thira Lal Bhusal sat down with the renowned cardiothoracic surgeon, also a former chair of Nepal Medical Council, to discuss his new project and other issues of Nepal’s health sector.

The exodus of Nepali doctors, nurses and other health professionals has emerged as a serious concern. What do you make of it?

This is a matter of concern, no doubt. Mass exodus of professionals is a concern in health and many other sectors. We don’t talk about other sectors much because those areas are not as sensitive. Health professionals are already in shortage. However, the number of the Good Standing Certificates and the No Objection Certificates that Nepal Medical Council provides for those who aspire to go abroad do not necessarily correspond to the actual number of those who migrate.

Those who are already abroad and want to change their jobs, seeking a promotion or extension, also want these certificates. For example, the UK asks for a new Good Standing Certificate for such purposes. So all those who have acquired GSCs from the NMC are not necessarily leaving the country. So the actual number of people going out every year should be less than what is calculated based on these two sources.

The Medical Education Commission (MEC) of the NMC gives no objection letters, but not every NOC gets converted to an admission or a job outside the country as you may apply in multiple places multiple times. So we have to actually verify the details of the actual number of people moving out. But we know this number is still high and it is increasing. That’s definitely of concern.

As a doctor, I am naturally more close to doctors and I can talk more authentically about them. Obviously other healthcare professionals are also going out in large numbers. We need a real policy debate on this. We’re producing enough nurses in Nepal. But many of them are going out, particularly the smarter ones, as they pass all the exams. We need to replace them with a new lot of trained nurses.

Many nurses trained and experienced here get a job in Australia, the UK and the US. Overall, people continue to go and the government has also signed agreements with foreign governments to formally send nurses. For instance, the government has an agreement with the UK government to recruit Nepali nurses in the UK healthcare sector. If we are losing too many, then should we be continuing this policy? If yes, what are the other negotiating points with those governments in terms of training our own local people here including doctors, nurses and others who choose to remain in the country?

I mean, just allowing them to go for jobs, make money as individual job holders is one thing, but if the government signs an agreement with another country, asking for some sort of reciprocal benefit for the country probably should be one agenda.

The pull and push factors play a key role. There is an attraction abroad due to job opportunities, more pay, and better working environment. Many are attracted by the living standards in a foreign country. Not everybody, by the way. There are push factors from Nepal. Health professionals are working in poor working and safety conditions. They are often under attack. They are underpaid. So that tends to provoke people to think that “it's not wise to stay here and it's better to go out”. So we all have to discuss how to change the working conditions here, including the various structures, living conditions and safety at the workplace. Obviously policy makers and the leaders of the country have to think: how do we make our country socially, politically more inclusive, and physically a safer place and more interesting place to live?

Do we need radical policy reforms for that?

We have to improve the environment here by changing the pay scales. If you pay trained doctors and nurses at par with other administrative staff, it's not going to work. The technically skilled trained people probably should be paid more. The governance has to improve.

We have a big private sector that runs hundreds of big hospitals and other health institutions. Has the private sector succeeded in attracting health professionals?

There is a big potential for change within the private sector. Unfortunately, the overall market size of Nepal’s health sector is not huge. And the healthcare workers, except for a small group of senior doctors, are not paid well even in the private sector. Overall, the private sector is struggling in Nepal due to multiple reasons. How do we change that? This leads to the discussion of health financing in Nepal. If there was an insurance reimbursement mechanism where people didn't have to pay from their pockets for their treatment, yet the hospitals would keep saving some money for increasing the perks, then that would change the scenario.

Fifty-four percent of all health expenditure comes out of the pockets of the patients. Few hospitals are making money, but most others are not saving much. That indirectly leads to a situation where the working conditions, salary structures of the nurses and doctors and other professionals are not attractive. We need a separate detailed discussion to analyse whether they're paying enough despite making money. But the overall pay scale, the revenues, the transactions within the health system, is not huge. So unless we improve the payment modalities, which is health insurance globally, it's hard even for the private institutions to be liberal with the pay.

In some places, the nurses are under-paid, even less than minimum wage requirement. That's unacceptable. So there's a lot of room to improve. And within the current revenue situations, they have to pay at least the minimum wage. But we're talking about the bigger perks. It's not just the minimum wages. It's a ‘poverty begets poverty’ kind of situation. So there are a number of other interventions that we could do.

Another thing, let's say, 2,000 or so doctors graduate each year in the country. But only 900 to 1,000 post graduate seats are available here. The remaining 1,000 will have to either go out of the country for those opportunities or get stuck with some part time work. So one of the best ways to retain the professionals is giving them training opportunities and secure career paths, opportunities for specialisations. Obviously, improving working conditions for the health care workers would help. Job opportunities in the government sector have not increased in the past 20 years, as its institutions have not increased. The private sector has grown, but not to the extent that all of them can be absorbed. We also need to look at how we deal with the destination countries. On the one hand, you're saying too many people are going abroad, on the other hand, you're signing contracts with foreign governments to send people. Also, contracts have been signed with the individuals and they're supposed to come back after completion of training. But those obligations, those contracts, are not being followed up.

We also have to look at how we bring those trained people back. Give them incentives to come back. We should work on increasing the attraction inside, giving them more secure work conditions. Also, somehow follow up on legal obligations that those people who have signed contracts and bonds with the government to come back. The overall governance has to improve in the country. We can change the situation, to an extent, but it's an uphill task.

What is the rate of returnees in this sector, now?

Very few. Maybe less than 5 percent. But, in the past, many of our seniors had been in the UK, and until some years ago returned after completion of the training programme. The government would send doctors for training: Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS), Membership of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons (MRCs), Membership of the Royal Colleges of Physicians in the United Kingdom (MRCP) training. They would get trained and come back. A large number of such professionals came back. But of late, a very limited number of doctors have come back.

Their return would be a great service to the country.

That's what I'm trying to bring up. I am not for restricting people from going abroad. That's their choice. The country has to work on improving the standards and attract people back home. Follow up on the individual commitments to come back. The country would benefit a lot because they come with more skills and knowledge.

The government has implemented the national health policy. Is it working?

I think the current model of insurance has not worked well. Particularly those who can pay, who are healthier, younger and well off, are not attracted to the national health insurance scheme. It is not sustainable in current form, size and shape. So, hopefully the Ministry of Health will take some solid steps to correct the drawbacks of that scheme. You cannot fund healthcare only from the government treasury. People have to learn to pay for their health even when they are not sick. They have to keep depositing a certain amount for the future when they get sick, or even when somebody else gets sick. We need to teach people to do that. We need to teach the politicians and policy makers about this ecosystem of health insurance.

The current health minister appears to be keen on making big announcements. How feasible are his promises?

I would refrain from commenting on it much because I'm part of the team that is supposed to give advice to the health ministry. Generally, I find him positive and proactive. I can only say that providing more advanced care will eventually have to be done through the insurance system, and that's the gist of our recommendation.

You have taken an initiative to build children’s hospitals in all seven provinces, which looks like an ambitious project. Please tell us about that.

Well, based on the nonprofit, and philanthropic financing model, it's a big project. But if you consider the needs of the children of this country, it's a small project. There are about 10 million children in Nepal.

The fundamental premise of this project is that children are not small adults. Globally, the care of children is provided by a set of specialists who are trained to handle and treat children. Nepal has not been able to embrace this trend. Having one or two hospitals for 10 million children across the country certainly is not enough to give them the optimal care. Children deserve specialised, focused pediatric care.

We don't have a pediatric care setup that provides all specialised care under one umbrella. I've done thousands of children's heart operations, but if those children had some other problems, like related to GI system, kidney, respiratory or others, then we would have to shift them somewhere else. So we should have a dedicated children's hospital where all the specialities are provided, under one umbrella.

Unless we decentralise general pediatric care, the high death rate of children is not going to come down. Nepal has committed to achieve the target of 12 deaths of neonates per 1,000 births by 2030. But for the past eight or 10 years, it has remained stagnant at 21 deaths per 1,000. The goal won’t be met by 2030 unless we change the way we treat our children.

In the past two to three years, we've been able to open one satellite hospital in Koshi Province. It has been working for more than one and a half years and served more than 115,000 children, as well as 15,000 emergency children's conditions. So that, in itself, is a great service in that part of the country. And the Kathmandu project is also taking shape now, and I hope that we will start some part of the service in the next six months.

What are the strategies and policies you have adopted to keep the project sustainable?

Keep working. That’s the mantra. It's a challenging place, by all means. You know, starting cardiac surgery 25 years ago was more challenging at the time. We changed the scenario by the way we provided care to cardiac patients. We also worked on improving some academic hospitals and institutions. Those were challenging too. I'm confident things will happen. Earning people's trust is the biggest source of energy and power.

In recent years, a high number of MBBS graduates have failed in the NMC licensing tests. Why is it happening?

It clearly indicates a mismatch between the standards of training by the institutions, the quality of their products, and the standards that Nepal Medical Council has set for licensing. There are a number of institutions in Nepal that produce doctors, nurses and health professionals. And there are varying quality of education in those institutions. There are institutions outside the country where the graduates come from, and their standard of education is also variable.

Why is our licensing test only knowledge based and doesn’t include a skills test?

We should have started a minimum set of skills testing for those who start practice, because unless they learn certain practical skills, they will not be able to treat people in real life. When I was the chair of the medical council, we were working to launch it, but my tenure ended before we could complete the project. But I think, If you start testing the skills, the outcomes are going to be worse.

Obviously, the number of failures in the licensing exam is concerning. From the point of view of safety of patients, there has to be a certain barrier before they go to practice. But we need to look at whether our licensing exams are of decent standards, and are our training institutions, the universities and academies offering training at par with national standards? So I think both sides have to be examined.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)