Editorial

What are you hiding?

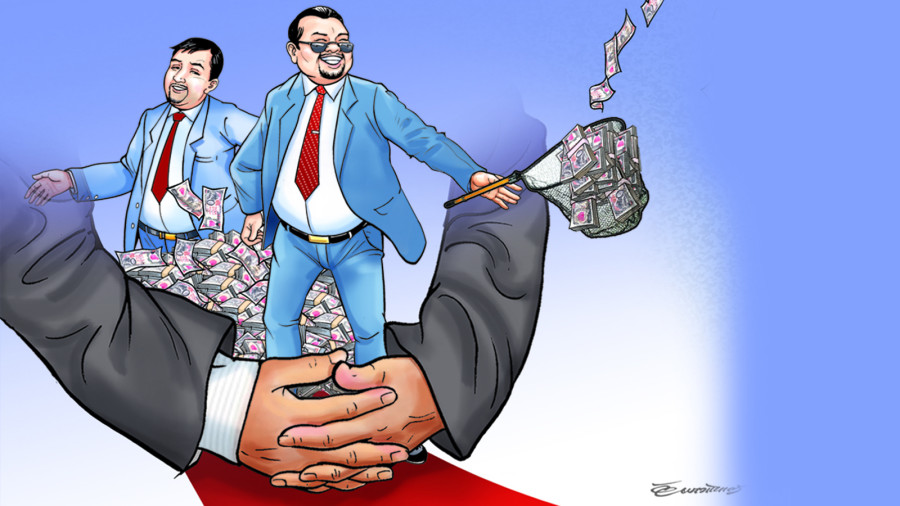

The government’s refusal to make property details of ministers public is problematic.

On April 21, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli formed a 15-member high-level good governance commission under his own leadership, with the likes of the finance minister, home minister and law minister as its members. Curiously, the prime minister chose to have a separate body directly under him instead of, say, adding teeth to the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), the constitutional anti-graft body and other related state organs. There is another reason to doubt Oli’s motives. Nearly 10 months since the formation of his government, he has yet to make public his own property details, or those of other members of his Cabinet. (This includes the inductees into the high-level good governance commission.) Besides its two most recent entrants, all other members of his Cabinet long ago submitted their property details to the Prime Minister’s Office. Yet the office refuses to divulge this information before the public. The government claims the right to do so, as it is not legally mandatory to disclose such details. That is indeed the case. Even so, before 2013—the year Khil Raj Regmi was appointed as the head of government by stepping on dubious legal grounds—successive governments used to routinely publish those details. And such disclosure served a vital purpose.

The sanctity of a democratic government rests not just on the rules and laws it must follow, but also on countless other norms and values that give it accountability in people’s eyes. This includes the expectation that people’s representatives show a minimum level of decorum—reflected in everything from how they dress to how they speak in public. This in turn helps establish a bond of trust between the electorate and their representatives. The same is true with the expectation that every government will publicise the property details of the members of the executive branch. Yet another excuse the government representatives offer for keeping such details under wraps is that their publication could tarnish the image of even clean Cabinet members in what is an environment of toxic abuse, especially online. But this argument too is flawed. First, if the property details are not made public, even clean members of the Cabinet will be looked upon suspiciously. This will be unjust on them. Second, true, some attempts might be made to twist such property details to fit certain narratives. But there are plenty of credible media and fact-checking outlets that can establish the truth of such information. And Nepali people have time and again proven, most importantly at the ballot box, that they can discern the right from the wrong.

So the most natural conclusion of the government’s refusal to make ministers’ property details public is that at least a few of them, perhaps even the prime minister, have something to hide. It is precisely these kinds of shady activities that are adding to people’s doubts over the prime minister. Rather than clean up and empower vital state organs, the current prime minister seems intent on centralising powers and covering up the dirt in his government. Instead of buttressing the pillars of good governance, Singha Durbar under Oli seems intent on dismantling them.

23.02°C Kathmandu

23.02°C Kathmandu