Editorial

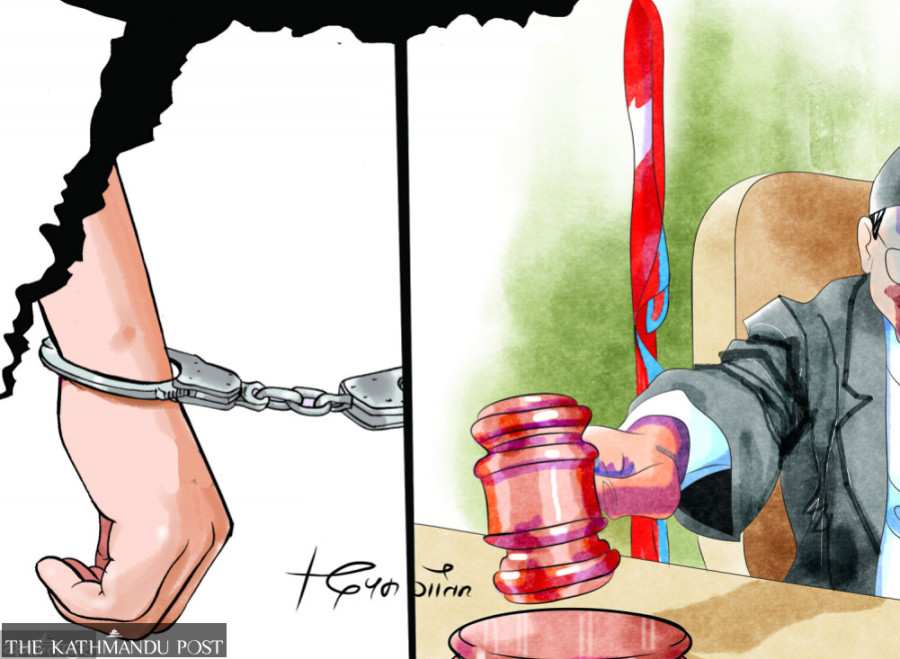

Politics of pardon

Arbitrary pardons and commutation of jail terms are part of a long trend of criminalisation of Nepali politics.

The Supreme Court has rightly ruled that the state’s executive branch does not have the privilege to arbitrarily grant pardons or commute jail terms of convicts. Issuing a full text of the decision to annul the presidential pardon given to Yog Raj Dhakal, a murder convict affiliated with the Nepali Congress, the court has now set definite criteria for such pardons. Last year, at the Cabinet’s recommendation, President Ramchandra Paudel pardoned the remaining jail terms of 670 convicts, including Dhakal. In July 2015, Dhakal, a gangster from Banke, had killed Chetan Manandhar in cold blood. Banke district court in April 2018 gave him a 20-year jail term. When he was pardoned, Dhakal had spent just eight years in jail.

Manandhar’s wife, Bharati Sherpa, had challenged the pardon in the Supreme Court. Then, a full bench of the court comprising justices Ishwar Prasad Khatiwada, Sapana Pradhan Malla and Kumar Chudal had, on November 2, 2023, annulled the pardon, saying it was constitutionally and legally flawed. Dhakal was arrested immediately after the court order—and now the full text of the verdict has come out. Particularly noteworthy about the text is its emphasis on the consent of the victims in such pardons. The court ruled that it is also vital that before taking such decisions on pardons, the victims have received adequate compensations and have been integrated into the society. Generally, the convicts must serve out their full jail terms, as prescribed by the judiciary, reads the full text. Even when exceptions are to be made, it is vital to consider the duration the convicts have served in jail in proportion to their jail term and the severity of the crime.

Every year, the President pardons or commutes jail terms of hundreds of convicts on the recommendation of the government, as per Article 276 of the Constitution of Nepal. The President may, under the law, grant pardons, suspend, commute or remit any sentence passed by any Court, judicial or quasi-judicial institution or administrative authority or institution, the article says. Many such decisions have landed in controversy. On May 28, 2018, then President Bidya Devi Bhandari pardoned 816 convicts, including Bal Krishna Dhungel, who was serving a jail term after being convicted of murdering Ujjan Kumar Shrestha from Okhaldhunga. The decision of President Paudel to grant amnesty to Tikapur massacre mastermind and former lawmaker Resham Chaudhary on the recommendation of Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal also attracted widespread ire.

This is all part of a long trend of criminalisation of Nepali politics. More and more, it appears like the entire government apparatus is geared towards serving a handful of powerful politicians. The latest and the most unexpected change in the ruling coalition has only bolstered this belief. A kind of politics is taking root where just about everything is justified to stay in power, including pardoning convicts to get their support to prop up ruling coalitions, as was the case with Chaudhary and his party last May. It is about time our ruling class realised that the rule of law is above and beyond their petty political calculations. Thankfully, until now our judiciary is still independent and strong enough to check such excesses of executive power.

8.22°C Kathmandu

8.22°C Kathmandu