Editorial

Bungling on BRI

A lot can be learned from the six largely unfruitful years of cooperation under the initiative.

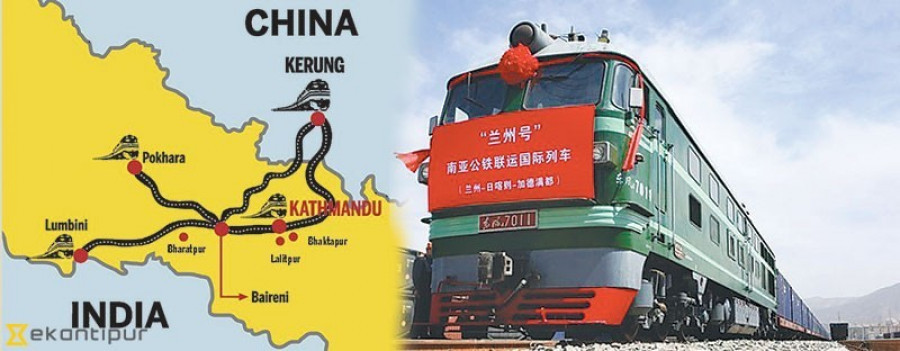

Seldom has Nepal prioritised projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since the country signed up to China’s signature foreign policy undertaking in May 2017. For much of the past six years, various communist governments were at the helm in Kathmandu. But despite their reported proximity to the Communist Party of China, none of the nine projects under consideration made much progress in this time. During the government leadership of the Nepali Congress, Beijing was told that Nepal was in no position to have a loan deal under the BRI and that any project under it should be built solely with Chinese grant. Part of the reason for the lack of progress is geopolitical: there is both overt and covert pressure on Nepali political leadership and bureaucracy to go easy on Chinese projects. But the story does not end there. Perhaps because of the Covid-19 pandemic and the resultant slowing of the Chinese economy, Beijing too appeared reluctant to take up projects abroad. Moreover, China has found it rather frustrating to deal with the constantly changing cast of characters in Kathmandu.

Whatever the reason, the lack of progress under the BRI is unfortunate for Nepal—and there is a lot of room for introspection. It is outrageous that Nepal’s sitting foreign minister is unaware of the need to periodically renew the Memorandum of Understanding on the BRI. The prime minister’s office is clueless too. The government machinery in Nepal appears so caught up in managing the mess in the country, its foreign policy priorities have gone haywire. There has been another troubling development as well. The Pushpa Kamal Dahal government has appeared a little too keen to hand over all vital hydropower projects to India, thereby circumscribing Nepal’s sovereignty. He seems to be making extra effort to humour the southern neighbour after repeatedly finding himself in New Delhi’s bad books in the past. This is also partly why even Dahal, someone who has traditionally been seen as ‘soft’ on China, has this time shown no inclination to pursue cooperation with the northern neighbour.

Nepal’s interest lies in maintaining carefully calibrated relations with both its neighbours. In China’s case, the big challenge for Nepal going ahead will be to derive maximum benefit from Beijing while also maintaining a safe political distance. There is no reason it cannot do so. But there is a caveat. The reason most of Nepal’s international friends, big and small, are suspicious is that its leaders tend to use foreign policy to serve their personal goals rather than to strengthen national interest. This makes them liable to sometimes tilt this way and sometimes that way, making them unreliable friends.

Nepal should learn to pick and choose: If a project is in national interest, it does not matter whether it comes from India, China or the US. But that is not enough. After all, Nepal had carefully chosen the nine projects to be pursued under the BRI. It is as important to have the tenacity to see these projects through. If the past six years of largely unfruitful cooperation under the BRI has taught us anything, it is that foreign actors cannot help us much if we are unsure about what we want.

20.4°C Kathmandu

20.4°C Kathmandu