Editorial

What’s in a language

The government should learn from the past blunders of promoting one language.

The idea that is singularity has always plagued society. It has caused immeasurable damage and is the single largest threat to the human aspiration for a multicultural world, where people of all races, religions, languages and cultures can live with dignity.

Two decades since the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation first recognised International Mother Language Day, in commemoration of the massive language movement in Dhaka for the Bangla language in 1952, several languages of the world are on the verge of extinction.

According to the UN body, at least 43 percent of the estimated 6,000 languages spoken in the world are endangered. It is a day of reckoning for communities that aspire to preserve and protect their mother tongue, and for governments to proactively implement targeted policies so that the ideas behind celebrating the day are actualised.

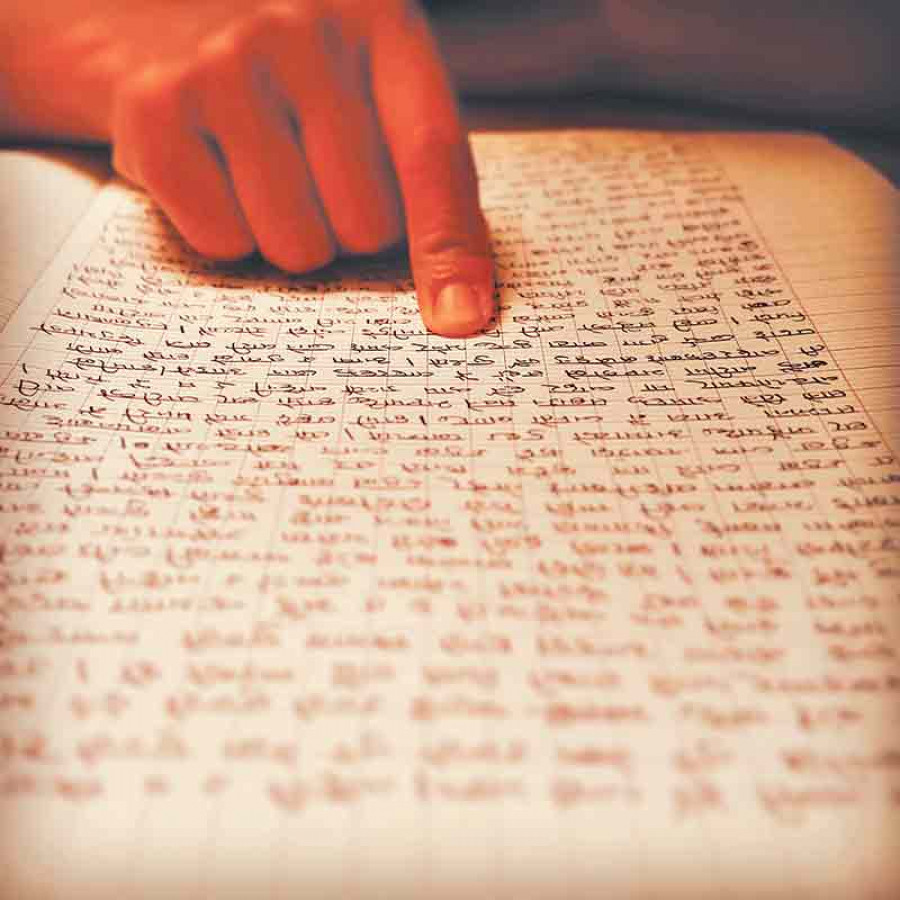

Language is an intangible heritage. It binds people across time and generations. If it weren’t for language, we wouldn’t be here today or any of our accomplishments and aspirations. We use language to communicate, to find meaning and to connect with the world. It is an inseparable element of our lives. Take language away, and the world would be enveloped in deafening silence, devoid of any understanding.

Death of a language thus is an immeasurable loss not just to the community, but to the entire human race because, with it, we would lose thousands of years of human understanding that continues to shape our world. We would lose our identity, culture and knowledge system that give us a sense of belonging. It goes without saying that language goes hand in hand with our identity, and it is our mother tongue that distinctly identifies us and our culture. It is what makes us unique and also contributes to our evolution and learning.

As part of the annual commemoration that honours linguistic diversity and multilingualism, the UN body this year has focused on inclusion, both in the classroom and in society. 'This is essential, because when 40 percent of the world’s inhabitants do not have access to education in the language they speak or understand best, it hinders their learning, as well as their access to heritage and cultural expressions', Audrey Azoulay, director-general of UNESCO, said in her message.

In the past few years, there have been positive steps at the grassroots level by language activists and communities that have started tutoring indigenous youth to speak and write their ancestral languages, and to engage with the works of literature produced in their language. The right to education through one’s mother tongue is also enshrined in the constitution of Nepal. The government must recognise these applaudable efforts and initiate flexible plans to implement this fundamental right to acquire education in the mother tongue. It cannot ignore the sufferings of indigenous languages and stay aloof to language movements that have a long history in Nepal.

According to the last statistical census of 2011, Nepal has 129 spoken languages, but at least 24 languages in Nepal are on the verge of extinction. The government has to understand that if there are no people left to speak the diverse languages and dialects spoken in Nepal, we cannot save them. It has to learn from the past blunders of promoting one language, which has contributed to this erosion of our linguistic heritage, and must actively engage with the communities to safeguard and revive these languages.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu