Editorial

Support the Sherpas

The government must do better than just handing out assurances.

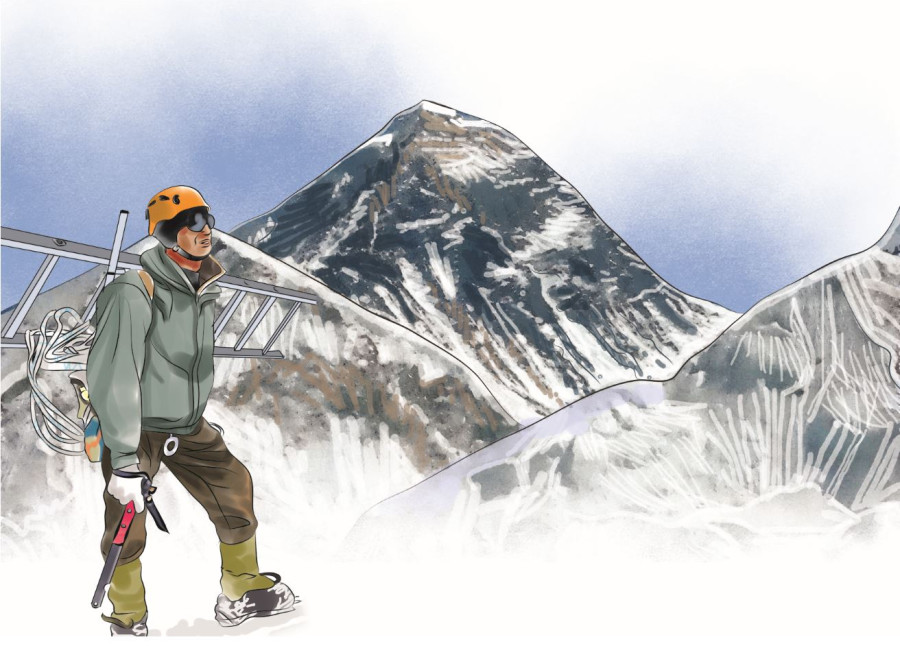

Thirteen of the world’s 14 peaks taller than 8,000 metres have been climbed in winter. But K2, the world’s second tallest mountain at 8,611 metres, remains elusive. Now, a massive 55-member group of climbing veterans from around the world, including 27 Sherpas from Nepal, are daring to take on a feat that has long been considered ‘mission impossible’—the first winter ascent of K2.

For starters, K2, which straddles the Pakistan-China border, is about 237 metres lower than Everest, and elite mountaineers say the mountain is technically difficult and more dangerous to climb even in the best conditions. In winter, when the weather is good only for two to three hours a day, the mountain is beyond savage. Avalanches are an ever-present risk, and temperatures could dip below minus 50 degrees Celsius and wind speeds measuring that of severe cyclones batter atop. To date, only 306 climbers have reached the summit, and 84 climbers have died attempting to climb it while all 30 previous winter summit attempts have failed, mostly due to weather, with the highest point reached being 7,400 metres.

The fresh bid to climb K2 in the winter will begin from December 21, and the expedition that could cost more than Rs200 million is expected to end by February 28. There is no margin of error for this extreme mission which will have to overcome the technical and strategic challenges amid the worst conditions imaginable. It comes as no surprise that leading this K2 winter mission in a year that brought mountaineering to a halt in the Himalaya due to Covid-19 restrictions is a Sherpa, and none other than Chhang Dawa Sherpa, the youngest mountaineer till date to climb all the 14 highest peaks.

While this is not the first time Sherpa climbers have been part of a winter attempt on K2, the world will be watching as 27 Sherpas join an elite team of climbers from Britain, Netherlands, Bulgaria, Poland, Greece, Spain, Romania, Switzerland, Italy, Chile, the United States and Finland. If successful, Chhang will not only add a new record under his belt, but his team of Sherpas will also bring home the glory of the ‘last great mountaineering challenge’ there is.

But for all the life-threatening risks they embrace and their superhuman abilities without which the mountaineering sector would collapse, the indomitable Sherpas receive little attention from the government and stakeholders who make the most of the money that flows in while the immeasurable tragedies of the Sherpa community are lost in the shadow of the mountains and in silent prayers of families who’ve lost their loved ones.

The climbing community which owes a great deal to the Sherpas can no longer ignore these heavy burdens and must give back to the community which has paid the highest prices. There ought to be a guarantee that a decent amount of profits also trickle down to the men and women who risk their lives to pursue one of the most dangerous jobs in the world.

The government must also do better than just handing out assurances and ensure that the Sherpas climb out of poverty. It must play a proactive role in introducing reforms and regulations in the mountaineering sector and invest in weather technology and mountaineering training to minimise the hazards of the job. It is time to put an end to the exploitation that has continued for decades and invest in the community that has contributed significantly to the national coffers.

8.55°C Kathmandu

8.55°C Kathmandu