Columns

Let the investigation begin

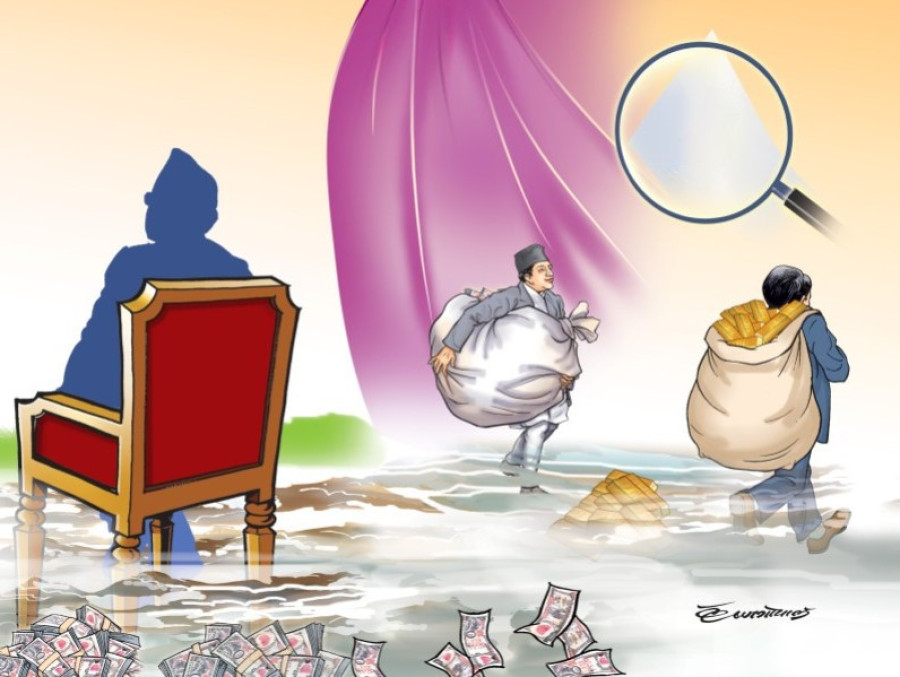

Large-scale corruption is not possible without the collusion of the political leadership.

Naresh Koirala

The government calls the current session of the Parliament a "legislative session." But its priority is to turn the six ordinances it crafted in a hurry—promulgated by the President a few days before the winter session of the Parliament commenced—into law. The suit of ordinances also includes the controversial bill to regulate social media.

While critical of the ordinances, the opposition parties in the Parliament have a different priority. They want an independent commission to investigate all previous corruption cases. Political corruption is not new to Nepal. It happened during the Panchayat autocracy and continued after the restoration of democracy in 1990. But it has never been as widespread and as large in scale as in the last 10 years, under the watch of Sher Bahadur Deuba of the Nepali Congress, Khagda Prasad Sharma Oli of the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist Leninist) and Puspa Kamal Dahal Prachanda of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre).

In Nepal's history, parliamentary or otherwise, the call for an open, collective investigation to hold the corrupt to account has never been so strong. This is a significant shift from the past. Whether or not the government concedes to the call, its impact is already visible.

The call and its impact

The opposition parties’ calls for an inquiry into corruption cases dominated the Parliament sessions last month. The Rastriya Swatantra Party, which contested the election with a promise to fight corruption, led them. Even the Nepal Communist Party (Maoist Centre), which is now in opposition, has joined them.

Corruption is considered the primary reason for Nepal's poor governance and chronically ailing economy. The deepening and widespread corruption has outraged the public and increased the demand for investigation. But why is the government reluctant to investigate?

Corruption scandals worth hundreds of millions could not have happened without the collusion of political leadership, and continuing the investigation could implicate political leaders. These scandals are the most discussed topic in Nepal these days. Words like ‘Giribandhu’; ‘wide body’; ‘gold smuggling’; ‘fake Bhutani saranarthi,’ ‘Baluwatar land’, ‘Omni, cantonment,’ and ‘Bansbari chhala jutta karkhana’—all associated with political corruption have now entered the ordinary public lexicon.

The impact of these discussions and the public's awareness of the politicians' maleficence is already evident in the shift in Prime Minister Oli's response to his alleged involvement in many of the significant cases. His response is now significantly feeble compared to his bullying protests until a few years ago.

About three years ago, when a member of Parliament implied Oli’s involvement in the Pashupati ‘Jalahari’ gold racket during a parliamentary discussion, Oli forced the suspension of parliamentary proceedings for three months. Oli shrugged off saying, “Such allegations cannot be made without proof.” These days, when corruption issues are discussed in the Parliament, he sits quietly, listening or walks out of the Parliament. When he does respond, it is only to repeat his well-worn phrase, “I am not corrupt; I do not get involved in corruption; I do not tolerate corruption.”

When journalists question him about the Giribandhu and wide body cases, in which Oli allegedly had a significant involvement, he walks away without offering an answer or chides them for asking baseless questions. "Where is the proof?" he counters. But there will be no proof without investigation—something he refuses to allow.

The support from young parliamentarians from the Nepali Congress, a party in governing alliance with the UML, at the risk of inviting ire from the party's senior leaders, attests to the popularity of the call. These young members know that people overwhelmingly support the investigation, and ignoring it will not be good for their long-term careers.

Oli is in a situation of "damned if you do, damned if you don't." If he concedes, he could be caught in the dragnet; if he does not, he will be seen as guilty in the public eye. "Where is the proof?" or “I am not corrupt, I do not …..” will not shield him.

The findings from the investigations and punishment of the guilty will be a significant deterrent against future corruption and could end the Deuba-Oli-Prachanda era from Nepali politics. It will also help revive constitutional bodies of check and balance, currently led by party hacks and compromised to serve partisan interests. Party leaders will not need their sycophants to head them if they do not intend to use them to serve personal or partisan interests.

Where from here?

Exposed and uncertain about handling the demand for the investigation, the Oli government is trying to regulate social media by turning the homonymous ordinance into a law. Without social media, much of the discussion on corruption would have been out of public reach. Experts argue that the proposed law restricts people's rights to information and freedom of the press. It is intended to ensure that people do not hear more than what the government wants them to. The International Federation of Journalists and its affiliates, the Federation of Nepali Journalists and the Nepal Press Union, all oppose this bill.

Even if the social media bill is passed as it is with a majority vote in Parliament, it will probably be challenged by its opponents in court. A bill legislated without consultation with stakeholders is impossible to enforce without using draconian force. Instead of pushing a bill to restrict the media, it would serve Oli and his fellow leaders from the NC and the Maoist party better if they spent some time, with their hands in their hearts, introspecting how they got where they are. If they truly believe they have done nothing wrong, accept the challenge and let an open, independent investigation confirm it. That is the proof the people want to see.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu