Columns

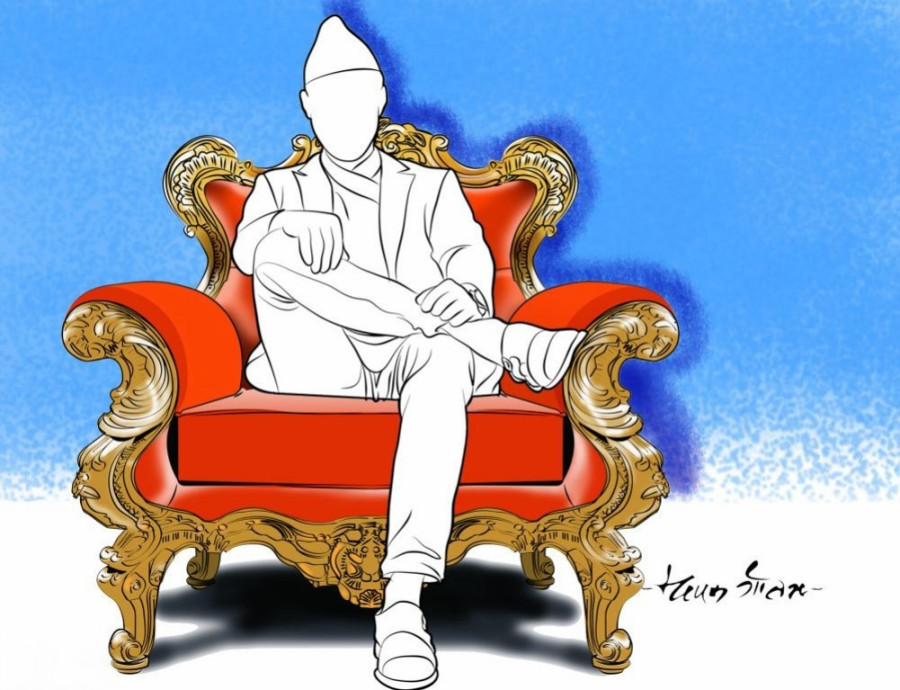

Of princes, power and politics

Nepali parties are building popular belief systems which are eroding the ethos of democracy.

Sucheta Pyakuryal

The prince, the ruler, has ruled humanity forever in various hues and forms. In Nepal, too, he came in different forms and shades. First, he came as a hereditary ruler of small principalities and then as the monarch of the Nepali nation-state. Today, he is a political man, elected by popular vote. His form may have changed over the years, but his core remains the same: masculine, calculating and power-hungry.

During medieval times in Italy, Niccolo Machiavelli drew up a sketch of an ideal ruler, which he titled The Prince. According to Machiavelli, he who was successful in acquiring and maintaining power was the most noble of all princes. This was probably the first European write-up which encouraged blatant obsession for political power. It also advised rulers to try and hold on to power by hook or crook. Only a ruler who manages to successfully retain power can be deemed as noble, said Machiavelli. Teleology, or the notion of “end justifying the means”, was portrayed as ethical in the game of “practical” politics. Realpolitik or pragmatism is something that every political actor needed to understand and imbibe was his book’s message.

The context, of course, was of medieval Europe. The base was agrarian, and the superstructures were feudal. In those days, the princes had either hereditary principalities that they inherited, or ecclesiastical principalities that belonged to churches, or new principalities that were recently annexed and/or mixed principalities that had both the old and the newly acquired spaces. The traits that a good prince should have, according to Machiavelli, were decisiveness or the ability to act deftly; pragmatism, which motivates the prince to choose self-interest over morality; deceit—an ability to deceive the subjects when necessary; parsimony or stinginess; and cruelty so that he can evoke fear among his subjects. He even evoked the beasts in princes: A lion to scare and keep the public in awe and a fox to “smell the snares”. Strangely, this formula seemed to have worked every time with every autocrat since it was written, including our own historical hereditary rulers.

Then came the era of enlightenment, which started the intellectual and philosophical movement that prioritised rational and empirical knowledge, natural law, human liberty, tolerance and community, constitutional governance, separation of religion and politics and most importantly, human progress and development. Individual sovereignty started taking priority in socio-political discourses, and governments were formed around the theme of citizen sovereignty. One base, undesirable human attribute, however, seemed unconquerable by all these developments, and that was the innate brutishness and the lust for power among ruling men that kept the argument of realpolitik relevant.

Despite various moral paradigms established on individual sovereignty and collective good, both Eastern and Western societies could never get rid of the Machiavellian prince that resided in contemporary rulers: The calculative, immoral, belligerent men who have dotted the modern political landscapes. It has been proven time and again that democratic systems cannot stop these Machiavellian actors from rising and ruling. Examples span from Trump to Putin, Netanyahu to Modi and Yogi, and we see hues of Machiavellianism in our party leaders. What is more worrying, however, is that this blatant immoral Machiavellianism has seeped into political parties, the modern political actors.

Interestingly, another 20th-century Italian philosopher, Antonio Gramsci, wrote “The Modern Prince” in his Prison Notebook, stating that political parties are the modern princes. “The myth-Prince cannot be a real person, a concrete individual. It can be only an organism, a social element in which the becoming concrete of a collective will, partially recognized and affirmed in action, has already begun,” and “it is the political party, the modern form in which the partial, collective wills that tend to become universal and total are gathered together,” wrote Gramsci. Regardless of the Gramscian Marxist perspective of how a political party should be, the fact that he equated the parties to Machiavelli’s prince should alarm those who believe in individual sovereignty and freedom.

Despite the concern, the parallel that he draws is brilliant: The same lack of scruples, unethical pragmaticism, an uncanny ability to morph and the upholding of traditional patriarchal values are some of the attributes of modern-day political parties or the modern princes. Although it is unclear what kind of parties Gramsci was talking about, he states that every political party is an expression of one social group.

This rings true in the case of Nepal. Political parties are composed of men from certain social strata. These men rule the parties with the value system they have been socialised with. Another important thing that he talks about is how the industrialists utilise all the political parties turn by turn. In addition, Gramsci asserts that “the historical rationality of numerical consensus (which is voting) is systematically falsified by the influence of wealth”. If what Gramsci wrote about the modern princes, i.e. the political parties, is correct, it is high time democracies started thinking about how to tame these modern princes—the parties, strip them of their lust for power as they had done to the medieval princes and force them to reorganise themselves as actual agents of moral, ethical democracy.

Parties, by manipulating political power and organised party-structures, are building a distinctive type of popular belief systems that are eroding the ethos of democracy. Be it the Nepali Congress with its strong capitalist interest group based on free-market beliefs, the Unified Marxist-Leninist and Maoists with their unionised syndicalism, or even Rastriya Prajatantra Party and its ideology of hyper-nationalism and monarchy, political parties with their interest-based politics are not upholding the greater good paradigm. They seem to have forgotten that the actual sovereigns are the people: Men, women, indigenous, urban, rural, both rich and poor people of Nepal whose will and aspirations they are instated to reflect and serve.

21.12°C Kathmandu

21.12°C Kathmandu