Columns

Can untouchability be eradicated in Nepal?

The declaration of an untouchability-free nation was a blatant lie on the part of the new ruling elites.

Mitra Pariyar

Academic and policy researchers, including Western anthropologists, have shown little interest in the lives and problems of the Nepali Dalit community. The neglect is such that, to this day, American professor Mary Cameron’s On the Edge of the Auspicious —published in 1998 and based on her field research in Bajhang District in the 1980s—remains the only notable monograph on the “untouchables”.

My guru at Oxford University, Professor David Gellner, and Krishna Adhikari, have done a commendable job of bringing out their edited volume Nepal’s Dalits in Transition (Vajra Books, 2024). Even though the work is based on their funded research a decade ago, it still largely reflects the situation of contemporary Dalits. As the old adage goes, something is better than nothing.

Recently, Dignity Initiative hosted a virtual conference on the book, where one of Professor Gellner’s comments caught my attention. He said that he wasn’t sure if the problem of untouchability would ever go away, but that one should always hope and strive for this noble objective. His observation made me question: Can one objectively think of eliminating the problem of untouchability from our society? My short answer is: No, or certainly not in the foreseeable future. Why is wiping out the beliefs and practices of untouchability an utterly unrealistic and infeasible goal? And what can be actually achieved?

The lie

On June 4, 2006, the Interim Parliament declared Nepal an untouchability-free nation. This unprecedented declaration followed the historic second People’s Movement, which snatched parliamentary democracy back from the autocratic monarchy. Many Dalits rejoiced, and they still remember and celebrate this special day with mass gatherings and lengthy speeches. Central and local governments often sponsor some of these events.

I can’t quite understand the excitement of Dalits, as the declaration hasn’t brought any change on the ground. Untouchability is still widely practised, and cases of caste humiliation and violence haven’t been reduced (The Amnesty International Report, May 2024). Its manifestations may have changed, and the intensity may have somewhat diminished, especially in the urban areas, but the problem persists.

It’s also unrealistic to wish for the total destruction of untouchability. A more nuanced understanding is essential to grasp this argument. Untouchability isn’t just a legal issue, as many people falsely believe. It is a fundamental part of the Hindu moral code deeply entrenched in our psyche, culture, customs, rites and rituals. Untouchability is deemed vital to preserving the sacred tradition of caste separation (for in-depth analysis by a native scholar, read Uddhab Pyakurel’s book, Reproduction of Inequality and Social Exclusion, Springer 2021).

More importantly, Dalits must realise that the declaration of a so-called untouchability-free nation was deceitful—a blatant lie on the part of the new ruling elites. The state pledged, knowing that it would never be fulfilled. The elites have known from the outset that it’s impossible to create a Nepal free from untouchability.

Over the decades, Dalits have been used to change political systems, including the bloody insurgency in the name of Maoism as well as the peaceful struggles of May-June 2006. To keep their Dalit cadres happy, the parties needed to give them something without actually giving them anything. That’s where the fake narrative of a country free from untouchability came in handy.

In any case, party leaders have no interest in curbing untouchability. Why should they? As Luis Dumont famously argued in his classic book, Homo Hierarchicus (1956), the notion of ritual purity and pollution is the backbone of the Hindu caste hierarchy. Sociologist Max Weber believed that there can be no Hindu without caste.

Social inequality gives the political elites, who are at the top of the food chain, their social capital, cultural superiority, moral authority, power and prestige. It legitimises their authority to govern and control those below them on the traditional social pyramid. Eliminating untouchability would, therefore, jeopardise their power.

Dalits practise untouchability

In reality, many Dalits themselves don’t want to eradicate the practice of untouchability. Victims of untouchability practising untouchability sounds oxymoronic, but it is an empirical fact.

Again, the French social scientist Dumont rightly argued in the aforementioned book that Indian Dalits replicate caste hierarchy within their own community. They, too, use the sacred concept of untouchability to exclude fellow Dalits from other castes. By extension, the same observation is true for Nepali Dalits.

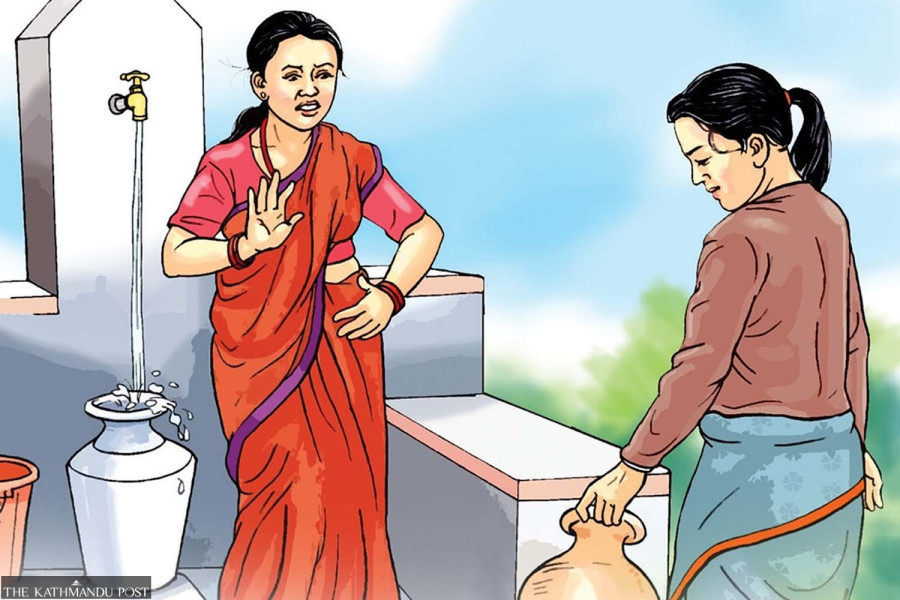

In swathes of Nepal’s hills, for instance, the blacksmiths exclude other Dalit castes such as tailors, shoemakers and musicians pretty much Iike Bahuns and Chhetris would do to them. Likewise, amongst Dalits in the Tarai plains, a man from the Paswan community would not share taps and wells with the Chamar, and the latter wouldn’t drink water touched by the Dom. Inter-caste marriage amongst Dalits across Nepal is a rarity.

The Dalit discourse, however, hardly touches the subject of internal discrimination. There’s little political will among Dalit leaders and activists to change the status quo. They decry untouchability practised upon them by the upper castes while turning a blind eye to their own beliefs and practices. This may be partly because, considering themselves bona fide Hindus, they take untouchability as a sacred tradition, which is also a part of their moral code, if not a natural phenomenon.

Way forward

It’s equally important to emphasise that untouchability is not a problem exclusive to Dalits. If untouchability were to be eradicated, most other castes and communities would also benefit. A degree of untouchability is practised at almost all levels of the caste ladder. Only the Upadhaya Bahuns, comprising 2.5 percent of the country’s population, are considered the pure caste. The rice cooked by ethnic groups isn’t consumed by Bahuns and Chhetris, for example.

Thus, untouchability is a multi-layered problem that is deeply entrenched in societal mores and cultures and customs, as well as in religious beliefs and practices. Moreover, other faiths like Buddhism, shamanism, Kirantism and, more recently, Christianity have also followed the Hindu tradition of ritual purity and impurity to a degree.

What this means is that it’s impossible to eliminate caste-based untouchability in Nepali society since it’s impossible to “annihilate” the caste system, as Dr BR Ambedkar argued for. Forget about Nepal, it seems challenging to eradicate untouchability even in diaspora communities, as my previous academic research has revealed amongst Nepalis residing in Britain (“Caste, Military, Migration: Nepali Gurkha Communities in Britain,” Ethnicities 2020) and Australia (“Travelling Castes: Nepalese Immigrants in Australia,” South Asian Diaspora 2019).

What is achievable is minimising the spread and intensity of the belief and practice of untouchability. For this, we must build a strong and independent Dalit liberation movement to pressurise the parties, the government, the parliament and the judiciary.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu