Columns

Policy recommendation to end untouchability

The state should introduce new laws and policies to enforce the constitutional and legal provisions against it.

Mitra Pariyar

Nepal is a de facto caste-apartheid state. A 2007 Human Rights Watch report on the “untouchables” of India observed, “The only parallel to the practice of untouchability was apartheid in South Africa.” The HRW has declared caste discrimination a form of “hidden apartheid”—an apt observation for Nepal as well.

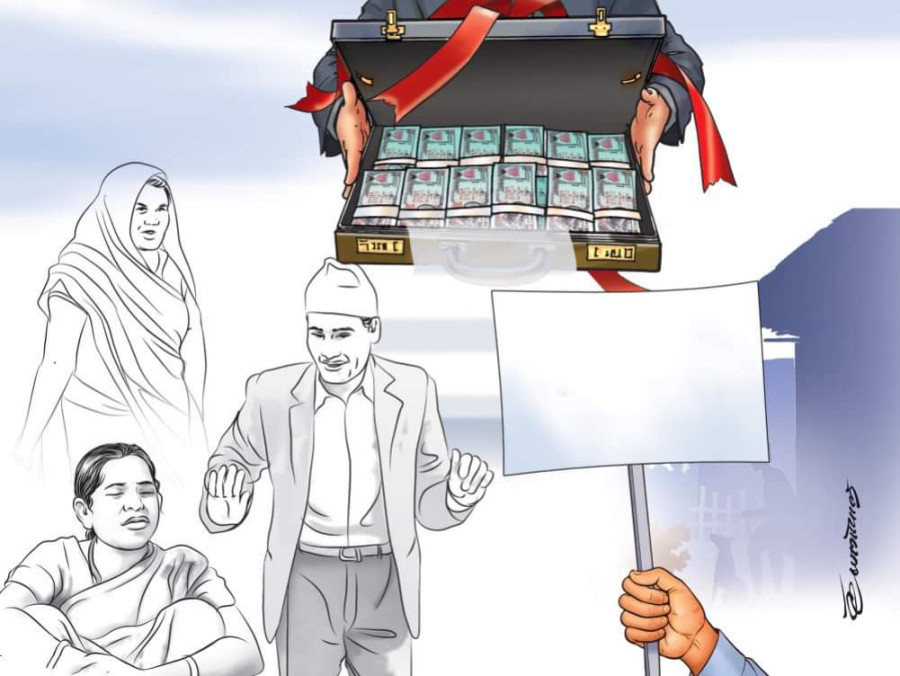

In the past years, caste hatred and exclusion have become more concealed yet pervasive in the Himalayan region; caste has also spread its tentacles in the global diaspora. Last month, Amnesty International criticised the government’s utter apathy and lack of accountability on the persistent plight of Dalits. The communist-populist alliance in government doesn’t seem to heed the call for change. This is clear from recently announced government policies, programmes and budgets for the fiscal year 2024-25. The authorities are bent on keeping caste hierarchy and untouchability sacred and solid.

Budget for ‘Dalit skills’

On March 21, 2022, attending a Dalit function in Kathmandu, Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal declared that he was making a big announcement for the dignity and freedom of the “untouchables”. So much so that, he said, they would not forget it in over a century. He hasn’t made his supposedly phenomenal Dalit project explicit, but some Dalits still haven’t given up their hopes.

Something came with this year’s budget for the Dalit community: Rs200 million to enhance Dalits’ traditional skills to create employment and promote their livelihood. This small yet seemingly significant budget has buoyed some Dalits. After all, as everybody says, something is better than nothing.

However, I’m sceptical about the effectiveness of the Dalit-centred budget. Is it a big enough pot of money to significantly impact the target population? Most people would say “No”. Even some prominent Dalit NGO personalities close to the governing parties have expressed their dissatisfaction with the amount. Equally, are Dalits the only beneficiaries of this new scheme? I don't think so.

The details of the intended 200-million project haven’t been developed yet. But it seems many non-Dalits will also get the support, especially those close to the ruling parties and leaders. There are at least two reasons for my understanding.

First is the very name of the entity the government plans to establish to use that money: A separate body called the “Dalit, Neglected and Oppressed Class Upliftment and Development Corporation.” The use of so many words is likely intended to involve the beneficiaries from different castes and social groups.

My suspicion stems from the second fact: In today’s Nepal, traditional Dalit skills—such as goldsmithing, tailoring, woodworking, and shoemaking—are no longer exclusively practised by Dalits. Once commercialised, many castes including the apex groups, have started these trades. So, skill enhancement projects will probably not be offered only to Dalits. I am not suggesting Dalits should have exclusive rights over these essential skills. It is neither practical nor proper to make such a case. My point is that it is probably wrong to think that the budget is for the betterment of Dalits.

Untouched untouchability

I have a serious objection to the utter lack of sensitivity towards the problems of Dalits, mainly the persistent practice of untouchability (hidden apartheid) in government policies, programmes and the budget. There is no single statement in the policies that mentions untouchability, let alone try to address it.

The same applies to the state and local authorities under the federal system. The biggest irony is found in the Karnali Province, where the Province Head, Tilak Pariyar, is a Dalit man with a long history of fighting against the state as part of the Maoist movement, with ending caste oppression as a primary goal. On May 23, he presented 84-point policies and programmes of the province. Study it in detail, and aside from lip service here and there, there is no serious concern about the situation of Dalits in Karnali who have been facing caste humiliation and violence like nowhere else in the country. Yet the authorities seem totally blind to the realities!

Recommended policy objectives

What should a responsible government do, both in Kathmandu and Karnali? First, the federal capital should become sensitive towards the plight of Dalits, who suffer tremendously due to popular beliefs and practices of ritual impurity. Then, the federal capital should design a national policy framework that could be followed by the lower authorities.

On a Sunday press meet, Caste Watch Network (CWN), a newly launched Dalit campaign group, recommended two fundamental policy objectives for tackling the complex problem of untouchability.

First, the state should introduce new laws and policies—sticks and carrots—to enforce the constitutional and legal provisions against untouchability. It could, for example, forge a policy of immediately suspending government officials guilty of excluding and humiliating Dalits. Elderly people who discriminate against Dalits could be deprived of their elderly pensions for two years or so. Any temple practising Dalit exclusion could be deprived of state support in the form of money and sacred offerings and sacrificial animals (yes, even the historical and famous temples like Gorakhkali and Manakamana do practise a form of social exclusion).

The second important policy objective would be to reform the religion. Some people frown at my suggestions about initiating religious and cultural reform, which they think takes many decades, if not centuries.

While we cannot easily rewrite casteist texts like Manusmriti and Parasaramriti, it is possible to achieve the reformation of some religious beliefs and practices over time. For that, the secular state should stand firm against religious dogma and formulate proper laws and implement them.

If no religious and/or cultural reform were possible at all, we would still be burning our mothers and sisters and other women alive on the sati pyres. If reform weren’t possible, we wouldn’t see a section of Bahuns drinking alcohol and consuming pork, and, as alluded to earlier, engaging in tailoring, drumming, shoemaking and goldsmithing.

Upper castes have deceived Dalits. They have forced religious and cultural transformations in areas that benefit them materially and in other ways. And they have been opposed to the reform of those areas of religious and cultural traditions that would ensure equal rights for Dalits. For example, a Bahun doesn’t become polluted by drinking and drumming; these transgressions do not anger his deities. But he thinks he and his family, lineage and other deities and spirits become polluted if a drummer enters his house.

Religious-cultural reform is not as tough as it seems. Governments and authorities at all levels should introduce new laws and policies and spend large sums to change the spiritual, religious and cultural spheres. Without this, we cannot do away with untouchability.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu