Columns

Oli’s brinkmanship

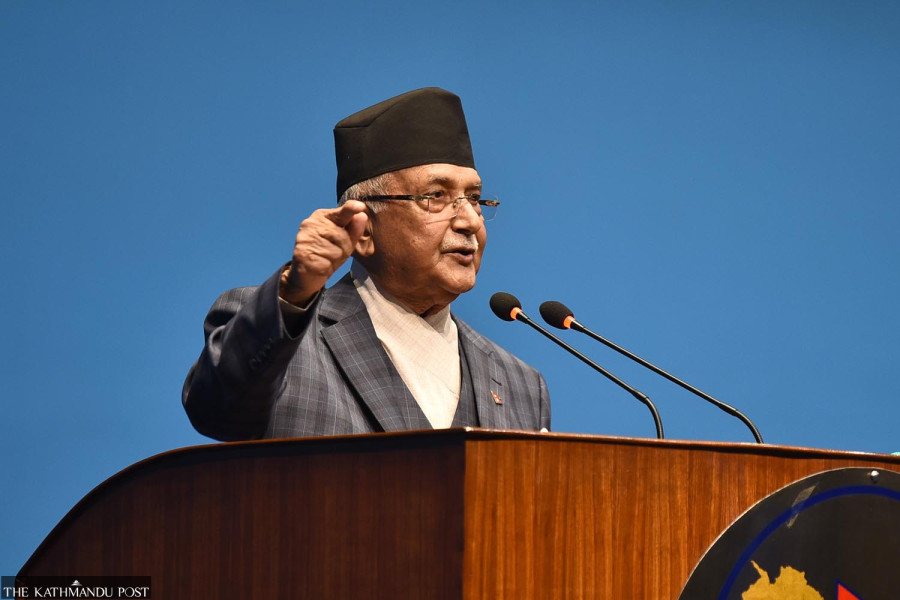

Dahal may be on the throne, but it is clear who is setting the rules of the game.

Anurag Acharya

In June 2020, Nepal’s Parliament ratified a new political map of the country, including geographical territories that were and still remain under the control of India. While some areas in the new map, especially the Kalapani region, were already a subject of dispute between the two countries, the communist government under Khadga Prasad Oli used its two-third parliamentary majority to include areas as far as Limpiyadhura unilaterally. For those who care to look at historical evidence, Nepal had never asserted its claim over Limpiyadhura, which was a territory lost after the Sugauli treaty of 1816. It was only in context to the existing dispute over the origin of the Kali river, which forms an international boundary in the treaty, that Nepal has claimed the Kalapani region and Lipulekh as its territory. India is cognisant of Nepal’s claim, and there is a joint committee looking at these boundary claims, with dialogue also happening at the Foreign Ministry level.

Oli’s move in 2020 was not sudden. He had advisors who clearly understood that Nepal did not fulfil the prerequisites for a sovereign claim over most of those territories under the international law, which mandates physical control of the territory with a resident population under active governance. In fact, the only claim that merits a mention, and which Nepal has strongly put across to India, is the credible evidence regarding Nepal governing the villages in the Kalapani region until a few decades back. Specifications of the evidence aside, what is clear is Nepal’s claims in the Kalapani region have been acknowledged by India and well-documented by the joint committee.

Oli’s come-back politics

When Oli came to power after the 2017 elections, he was riding on the wave of hyper-nationalism he had managed to stoke in the aftermath of the 2015 Indian blockade. While the Madhesh-based parties had indeed initiated the border obstruction to pressure Kathmandu’s political centre into conceding to their demands on the new constitution, the Narendra Modi government that had just come to power in New Delhi was blamed for actively enforcing the blockade. This is a claim India continues to deny. Whatever the truth, the blockade provided an opportune moment for Oli, whose political career was ailing at the time. He not only managed to sideline his bête noire, Madhav Kumar Nepal, inside the party but he also struck a deal with politically insecure Pushpa Kamal Dahal to cobble up a two-thirds majority in the 2017 elections. What happened next has continued to haunt Nepal’s relationship with India.

Oli, of all the communist leaders of his generation, best understands that if there is one issue that could mobilise the population across the country, it is our collective sense of insecurity against what we perceive to be India’s over-reach and micro-management of Nepali politics. An average Nepali consumes Indian products, watches Bollywood movies, and supports an IPL team, all the while disdaining what they consider Indian interference in Nepali affairs.

To be fair, such a mindset is not uncommon in a relationship between two countries that are disproportionate in geography, demography, economy or military capability. The tendency of the political class to weaponise public sentiments and insecurity against a larger neighbour for domestic electoral politics is not uncommon either. Autocratic and populist regimes across the world have consolidated their hold over power by stoking hate or fear against a perceived enemy state, painting their domestic opposition as weak and incapable of defending national interests. The definition of the enemy state and the national interests, in such cases, are often dictated by those in power to suit their divisive politics.

When Oli refused to concede party or government leadership, Pushpa Kamal Dahal wrecked the mighty two-thirds government with the help of the disgruntled Madhav Kumar Nepal faction. Nepali Congress had no issues cashing in on this division, allowing the party’s president, Sher Bahadur Deuba, to become the Prime Minister in July 2021. Upon becoming premier, Deuba and his coalition partner Dahal did all they could to normalise the relationship with New Delhi. There was little talk about the controversial map or the Eminent Persons’ Group (EPG) report, which had both become irritants in the bilateral relationship. After the 2022 elections, when Dahal became prime minister, New Delhi reciprocated by supporting Nepal’s ambitions to invest in large infrastructures and export power in the Indian market and potentially to Bangladesh. In doing so, New Delhi expected to regain some of the trust it had lost after the 2015 blockade.

But Oli is a seasoned politician, a political maverick who can see two steps ahead of his competitors. He sensed Dahal’s distrust of his coalition partners, his personal anxieties and insecurity about the future of his party, which he felt was dealt an under-hand during the division of electoral seats. China, which had openly helped in cobbling up the previous left unity, has been more cautious this time. But there is plenty to read between frequent delegations shuttling between Kathmandu and Beijing over the past year. In any case, Oli convinced Dahal to leave the Nepali Congress coalition and continue in power with UML’s support, with a vague promise of a long-term (electoral) partnership. Upendra Yadav’s Janata Samajwadi Party and the newly established Rastriya Swatantra Party were offered attractive cabinet positions in exchange for their support as well. Yadav, though, has left the coalition after the split of his party.

Perilous brinkmanship

If Pushpa Kamal Dahal believes that the UML chairman took all the trouble of bringing down the NC-led coalition just to watch the game from the sidelines, he needs to change his advisors. He may have generously allowed Dahal to continue on the throne, but it is clear who is setting the rules of the game. The recent decision by the current government to include Nepal’s new map in its currency note has Oli’s footprints all over it. However, his brinkmanship with India could have serious ramifications for the country. Not only will such misadventures jeopardise Nepal’s crucial economic interests, especially in the cross-border energy market where the private sector has invested billions of dollars, our ambition to access the trade route to Bangladesh and further east will not see the light of the day.

As the war in Ukraine drags on and the conflict in Gaza worsens, Washington is already zooming out from the Indo-Pacific region. This could provide a much-needed conducive environment for a rapprochement between New Delhi and Beijing, something Indian Prime Minister Modi has hinted at recently. Nepali communists must read the changing geopolitical horizon and understand the days of playing one neighbour against the other may not last for long. Nepal is better off drawing complementarities in its relationship with the two neighbours, allowing them to compete for economic interests on its own terms.

8.79°C Kathmandu

8.79°C Kathmandu